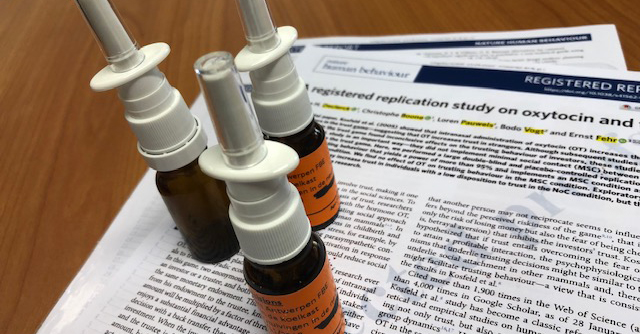

More than a decade ago, a paper was published in Nature showing that oxytocin, a hormone which is better known for its role in childbirth and breastfeeding, increased men’s trusting behavior in an economic game.

A surge of behavioral studies on the social functions of oxytocin followed, which may in part have been inspired by the ease with which oxytocin can be intranasally administered to humans. However, these studies raised more questions than they answered, as findings were inconsistent and conflicting, clouding the oxytocin-trust link with confusion.

Follow-up experiments suffered from small sample sizes, or the researchers did not use the same methods as in the original study they set out to repeat. This is very important because small changes in the experimental can have a large impact on how oxytocin works and on how it will affect behavior.

“For example, behavioral economic experiments are typically conducted in an anonymous setting in order to reduce the possibility that the results are influenced by incidental likings. But if we want to understand the social functions of oxytocin, anonymity may be a problem.”

Research set-up

To resolve these issues, we tested, with a large sample size, if oxytocin increases trust in both an anonymous and a minimal social contact condition. In the former, all participants in the experiment sat in private cubicles and never met, while in the latter, they first met in small groups of eight and were seated at the same table prior to the experiment, where they could see and talk to each other. While seated, they filled out questionnaires.

Our main hypothesis, which was pre-registered in Nature Human Behaviour before conducting the study, was that the increase in trust induced by oxytocin would be higher in the minimal social contact condition.

We collected data on 677 males in Magdeburg, Germany, and Antwerp, Belgium. This sample size exceeds the minimal requirement to be able to observe a statistically significant effect of oxytocin. Because we cannot be sure that oxytocin affects men and women alike, we tested only males. Half of the participants in the study received a nasal spray containing oxytocin, while the other half received an identical spray containing a placebo.

A game of trust

Trusting behavior was assessed with a trust game in which the first-mover can earn substantial amounts by transferring money to another person. At the same time, they can lose everything when this person is untrustworthy and does not reciprocate a transfer. Although players never knew the identity of their interaction partners, in the minimal social contact condition, they were told that they were playing the game with one of the other seven people they had just met. We presumed that this would provide positive social cues, and that oxytocin would enhance these cues so that trust would be facilitated.

The results

In fact, the results did not confirm the main hypothesis that oxytocin (as opposed to a placebo) increases trusting behaviour in the social contact condition.

- If anything, the social contact condition may have opposed the effect of oxytocin. The prior shared experience may have reduced feelings of connectedness between participants, and generated negative social cues rather than positive ones.

- Connectedness was greater in the anonymous condition, where oxytocin (relative to placebo) appeared to increase trusting behaviour, but only for those participants who had low intrinsic dispositions to trust.

“The question – does oxytocin increase trust – does not have a simple answer. If we generalize across all people in all situations, the answer is no. Our data does suggest that oxytocin may facilitate trust for men who have a generally low disposition to trust, at least in situations where they do not perceive negative social cues. In retrospect, this may sound like a natural result, but it was not anticipated and should be treated with caution.”

Future recommendations

This study points to yet another conclusion, namely how difficult it is to conduct and interpret behavioural data from hormone-administration experiments. Based on our experience, we can recommend the following for future research:

Avoid overinterpreting findings. Studies should be preregistered with explicitly formulated hypotheses and statistical tests to examine these hypotheses, including an ex-ante power analyses of the sample size.

Second, focusing on relevant individual differences can create high additional value. For example, targeting individuals with low dispositional trust or other social deficits will not only avoid ceiling effects, but potentially uncover promising clinical effects, provided that the hypotheses are pre-registered.

Experimenters should be vigilant regarding contextual cues that either facilitate or hamper approach behaviour, as these cues may change the direction of oxytocin’s effect. There is a growing need to assess how these cues are perceived by different people in order to get a grip on how context, individual differences and oxytocin interact.

Researchers should be well-aware of the workload involved in designing a sufficiently large experiment that pays attention to the tedious details regarding context and individual differences.

Finally, we do not sufficiently understand how, why and when oxytocin works in order to make accurate predictions. Therefore, empirically grounded theory development on how oxytocin may affect social behaviour in humans is crucial. This will require interdisciplinary work (in humans and animals alike) that includes, more fine-grained investigations on (for example) how oxytocin-related brain activity is triggered in response to different environmental stimuli and cues.

Taken together, we believe that these suggestions may help to improve future research on the effects of oxytocin.

Authors: Carolyn H. Declerck, Christophe Boone, Bodo Vogt, Loren Pauwels, and Ernst Fehr

Discover the activities of the Management Research Group at the University of Antwerp.