Economie Ontcijferd

A good knowledge of mathematics is essential if you want to understand how businesses and economics work. Whether we’re talking about interest calculation, price elasticity, market research,… without the numbers, it just won’t add up.

For many Belgian high school students, this aspect of economics remains unknown and underexposed. That is why during ‘Economie Ontcijferd’, students discover mathematics in various fields of economics by looking at practical cases and applications.

Economic implications of climate action and inaction

One of those classes, taught by Prof. Steven Van Passel, is about the economic implications of climate action and inaction. A brief summary:

“Greenhouse gas emissions are external costs and are therefore not correctly reflected in the prices of our products. According to Sir Nicholas Stern, this is one of the biggest market failures. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a public good and we are often faced with freeloaders who do not (sufficiently) reduce their emissions.

To achieve the climate goals, action is needed. And we study the economic impact of this by comparing the costs (of inaction) versus the benefits of climate mitigation. A very important element here is time dilation: 1 euro now is worth more than 1 euro in 1 year and much more than 1 euro in 20 years. This is because we are impatient, we face uncertainty and we can invest money we have now in growth.

Time settlement based on the discount rate

The way we settle time therefore has an enormous impact in the long term. We do this settlement on the basis of the discount rate. This rate indicates how the value of money changes over time: 100 euros over 50 years at a discount rate of 5% is less than 10 euros, while the same amount over 50 years at a discount rate of 3% is almost three times higher.

Climate economists work with models where they compare the costs of inaction with the benefits of climate action. If we can invest resources in productive climate mitigation and thus achieve clear qualitative growth with fewer emissions, we should not hesitate to do so. After all, then it’s a clear win-win situation. If we have to invest resources in climate mitigation when we could also invest them in more productive investments, we need to make a correct cost-benefit analysis. The level of our investment then depends on how we look at the future (and thus on our time settlement).

Stern vs. Nordhaus

A well-known contradiction here is choosing a low discount rate (1-1.5%) like Sir Nicholas Stern or a higher one (5-6%) like William Nordhaus (Nobel Prize winner in Economics in 2018). Nordhaus based this on our actual behavior and argued that the current generation counts more than future generations (because in his reasoning they will be richer anyway). Stern, in turn, takes a utilitarian perspective and argues that people are worth the same, both now and in the future. In short, Stern (and the 2006 Stern Report) argues that we must act quickly because, the benefits of action are great and the costs of climate change can be very high. Nordhaus argues that we need to act but that climate damage is a gradual process and that we need to make the right investments at the right time.

Most economic models (including those of Stern and Nordhaus) make the necessary assumptions about the damage of climate warming and assume economic damage within a workable temperature increase. However, large temperature increases due to, for example, crossing certain tipping points, result in much higher costs and jeopardize the stability of our economic system.

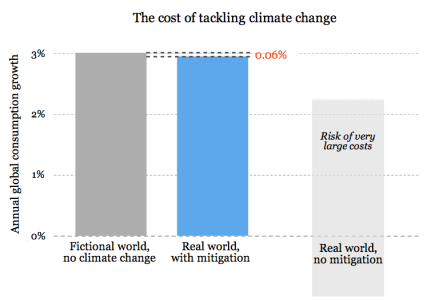

Climate-mitigation-costs

Figure: The IPCC estimated the cost of climate mitigation in its 5th Assessment Report (2014). They indicated that the measures needed to limit warming to 2 degrees would cost an average of 0.06% of consumption growth annually. This cost pales next to the cost of inaction, and moreover does not take into account the possible co-benefits (e.g. less air pollution and lower health costs). Read more.

Figure: The IPCC estimated the cost of climate mitigation in its 5th Assessment Report (2014). They indicated that the measures needed to limit warming to 2 degrees would cost an average of 0.06% of consumption growth annually. This cost pales next to the cost of inaction, and moreover does not take into account the possible co-benefits (e.g. less air pollution and lower health costs). Read more.

In any case, it is clear that we are still under-investing. How much additional effort we need to make, depends on your view of the future. But regardless, greater efforts need to be made. By the way, the vast majority of economists favor a (global) carbon price. Carbon taxes (and possibly repayment via dividends) are cost-effective and are dynamically efficient because they encourage innovation. But that is a whole other story….”