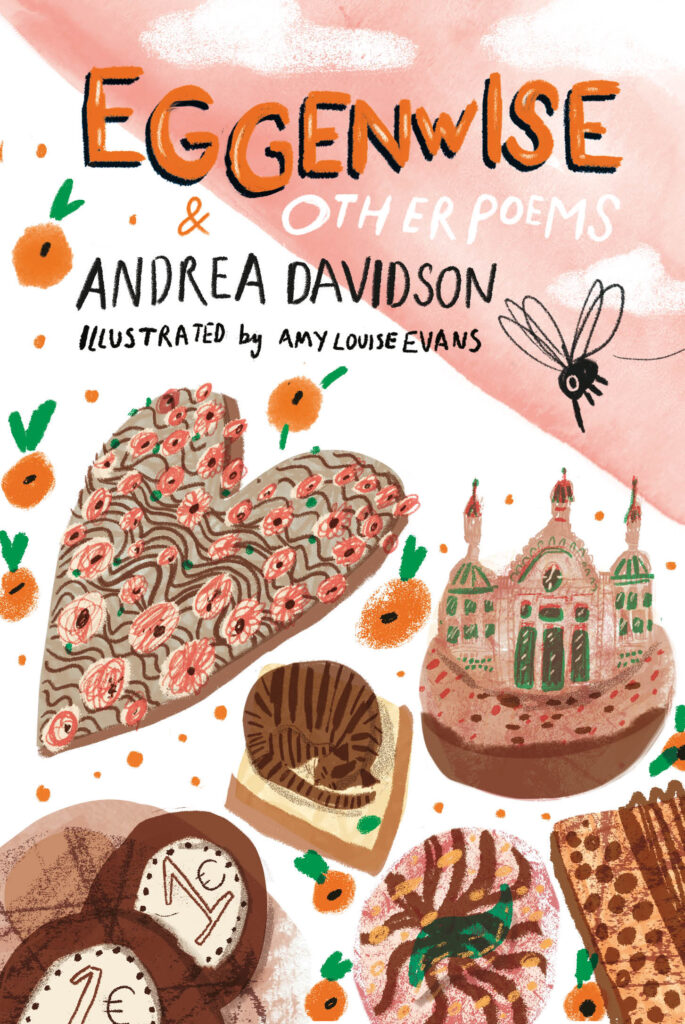

In the poetry collection Eggenwise, Andrea Davidson beautifully captures the paradox of feeling homesick and at home in a foreign land, a sentiment familiar to many who have ventured far from their roots. Andrea is originally from Toronto, Canada, but has been living in Leuven since the start of her doctoral research about the children’s book author Aidan Chambers. She currently continues working on Chambers as a postdoctoral researcher on the project Constructing Age for Young Readers (CAFYR). In her poems which are now published by The Emma Press, Andrea documents observations about her new home and the little quirks of the Dutch language. We sat down with her for a talk about writing Eggenwise.

(Andrea’s photo by Natacha De Mahieu)

Congratulations with your debut Eggenwise! How did this poetry collection come about?

Andrea: “I started writing it in isolation during a COVID-19 lockdown. We had just moved to a new apartment with a tiny balcony, just about one metre lengthwise and half a metre the other way. Still, we got a table and chairs, and I would sit out there when the weather was nice. One day, I sat there to work on my PhD dissertation, but instead I started describing what I could see. These writings turned into poems, for instance about the friendly neighbourhood cat that visits every day. That balcony became a place for me to let my imagination wander.

I had only been living in Belgium for one year before COVID-19 began so I was only just getting used to being here–and then everything changed. This period locked at home made me reflect a lot about what I had seen in this new country and how I felt in relation to this place. Even though I could not actually travel around, I was still exploring Belgium as a newcomer through writing about the experiences I had already had here.”

I think that idea of giving a new perspective on Belgium comes across very well; especially since this place is so familiar to me as a native. You have a keen eye for detail too, particularly in how you write about language. I thought it was amazing how you noted down the way that Dutch words sound in English.

“Well, that’s the other part of this story: I had been studying Dutch and took online Dutch classes during the lockdown. I started reading Dutch poetry, even though I really struggled with it. I still think poetry is something for which you really need a deep understanding of the language to get, although in Eggenwise I tried to write poetry that you could enjoy even without being very knowledgeable of English. To get a grasp of Dutch poetry, I tried translating some poems into English. Doing this made me consider the way that Dutch words sound to me. It turned into a sort of a game.

I loved learning Dutch because it is a wonderful challenge to try to express myself in a new language. Learning Dutch in particular was fun because of the sounds. I enjoy moving my mouth in different ways. It was almost like learning an instrument. When I learned to play the trombone, I had to build new muscles to be able to play it properly. In a new language, you also must move your mouth and even your whole body in different ways. When I first moved here, I felt sometimes like I couldn’t read people’s body language. It was helpful that we also learned about cultural competence in the Dutch classes at Linguapolis. They actually said that learning to be in a new culture is like the stages of grief: you have positive experiences in which you quickly understand things and then negative experiences in which it seems like you haven’t learned anything yet, until you begin to acculturate. There was a whole puzzle behind the Dutch language for me.”

You started translating poetry to get a feel for both the poetry and language. Had you been writing poetry for a long while before you started the poems collected in Eggenwise?

“Yes, I had written poetry for years. I think you have to write a lot just to learn how to do it, and then eventually you are able to do it well. Because I teach Literature and have been researching it, I think all the time about how a text is constructed. In that sense, there is a strong connection between the writing that I do and my research. I am asking very similar questions. For me, part of understanding how authors write is to try doing it myself.”

So your poetry and research are connected through the questions you ask yourself in the writing process?

“On the one hand, when you study literature, you are always thinking about the way a text is constructed and what meaning this has. For my PhD, I researched why Aidan Chambers chose to write in a certain way. In his archive I found all the different versions of some of his novels. Reading them, I could figure out what decisions he made when he revised one version into another. I had to ask, why would he decide to change the structure of a text, the name of a character or even just a single word?

On the other hand, researching children’s and Young Adult literature also influenced Eggenwise because I had become aware of keeping the reader in mind. What do authors have to do to connect with readers, especially if they are much younger—or older? I tried to do this myself.

Especially during the lockdown, I wrote poetry to take a break from academic writing. It’s a very different feeling from writing my dissertation. You don’t have to explain every little thing in a poem, which is the sometimes-exhausting part of academic writing. In a poem you’re allowed to keep secrets.”

Is the book more directed to children?

“When The Emma Press accepted the book, they asked me who I thought the audience was. My answer was that I hope everyone will enjoy the poems because many of them are very playful, like you might see in a work of children’s poetry. For instance, the first few pages of Eggenwise are all about this fly that was in my house. I gave that fly a whole personality. That poem is very childish in a way, while others are about adulthood experiences like having a job and falling in love. Not every poem is necessarily for the same age of reader. I don’t think there is only one reader anyhow.”

Right, because playfulness shouldn’t be limited to children.

“Yes! And vice versa. Take a story about adults falling in love: that is a life experience children haven’t had, but that doesn’t mean they wouldn’t understand it.”

Writing poetry is a way of finding an even deeper enjoyment, to become a part it by giving it a lot of thought and then turning it into words on paper.

Andrea Davidson

So how would you describe your book to someone who hasn’t read it yet?

“My book is about growing up, living abroad, learning a language, falling in love, and noticing the world around you.”

The blurb even says that your poems “notice the remarkable in the everyday”. Is documenting those small everyday moments a motivation for you to write poetry?

“Imagine it’s beautiful weather outside. You could acknowledge that it is beautiful out there, or you could appreciate that sunny day by running outside and going to a green space to see the light shine through the trees. For me, writing poetry is a way of finding an even deeper enjoyment, to become a part whatever it is that inspired me by giving it a lot of thought and then turning it into words.”

How does your writing process work? For example, did you immediately make notes about the fly in your room?

“Usually, the idea for a poem comes very quickly to me but it does take a while after that for the poem to take shape. It’s quite contradictory because I instantly realise if there’s a poem in there somewhere, but then it’s a very slow process to make the poem. I couldn’t tell you now why that fly was so inspiring. It was just a distraction that I kept thinking about. To find the title “Eggenwise,” it all started with mulling over the word “eigenwijs” [wayward, stubborn]. I wrote down some words that sounded like “eigenwijs.” Later I arranged them in a new order and wrote them into lines until I found the final form.”

So just like Aidan Chambers, you find yourself revising a lot of the small elements.

“I think I do it even more than he does, actually.”

Do you feel that Aidan Chambers has had a big influence on your writing?

“He certainly has been a big part of my life for the last few years. He wasn’t a partner in my research, but we corresponded. I even went to his home and, for my research, read parts of his diaries. Our lives were connected for quite a while, but in a one-sided way. I don’t know how much he knows about me, but I’m sure he found out things about me through his intuition and his own wide, knowledgeable network.

I don’t actually know whether he artistically was much of an influence on me, yet I did get the chance to learn about artistic process from him. This made me realize things such as: he really changed his mind sometimes. Or he started writing with just one single word, then watched where it took him. The whole mystery of how his books came to be written and published was lifted through my study of his process. This made me more aware of how I write too. I had been writing for years, but quite randomly. For Eggenwise I finally put all my poems in order. So, I wouldn’t say Chambers had a direct influence on me, but my PhD research on him did.”

Eggenwise

Order the book from the publisher The Emma Press or from your local bookseller.