English blog post below

Het geschonden hart van Europa. Een festival van kunst, literatuur en film over Bosnië-Herzegovina

Antwerpen, De Studio, 18 mei 2022

Enkele impressies

“Door Bosnië rijden vereist een andere dimensie: een omgekeerd wormgat dat niet naar een externe, reële bestemming leidt, maar naar de sombere, amper doorwaadbare diepte van je eigen wezen.” Tot die weinig opbeurende conclusie komt Sara, het fictieve hoofdpersonage van Lana Bastašić’ overdonderende debuutroman Vang de haas, terwijl ze samen met haar vroegere jeugdvriendin Lejla door het land rijdt, op zoek naar de tijdens de oorlog verdwenen broer van deze laatste.

Ook tijdens het cultuurfestival Het geschonden hart van Europa, dat Power in History in samenwerking met UCSIA inrichtte naar aanleiding van de dertigste verjaardag van het onafhankelijke Bosnië-Herzegovina, was de grondtoon er geen van groot optimisme. Hoe kan het ook anders? Het land werd geboren te midden van een bloedige oorlog die tot vandaag diepe sporen nalaat. Ongeveer honderdduizend Bosniërs overleden ten gevolge van de oorlog, een veelvoud daarvan ontvluchtte het land. De Bosnische samenleving, waarin moslims, katholieken, orthodoxe christenen, Joden, Roma en atheïsten zij aan zij hadden geleefd, was hardhandig uit elkaar geslagen. In de plaats daarvan kwam een complexe politieke constellatie waarin etniciteit een allesbepalende factor is. De resultaten van de etnische zuivering die had plaatsgevonden werden grotendeels bevestigd door het Dayton-akkoord van december 1995. Dat akkoord bevestigde het bestaan van een semi-autonome Servische Republiek binnen de federale republiek Bosnië-Herzegovina. Dat de politieke elites van deze Republika Srpska vandaag pogingen ondernemen om zich uit het Bosnische verband terug te trekken, toont hoe onzeker de toestand nog altijd is. In deze context is de oorlog in Oekraïne voor veel Bosniakken – Bosniërs die zich met een islamitische traditie verbinden – een fundamenteel traumatiserende ervaring, die hun hooguit oppervlakkig geheelde wonden weer brutaal openrijt.

En toch was er tijdens Het geschonden hart van Europa ook veel ruimte voor schoonheid, warmte, verbinding en zelfs een beetje hoop. Diverse cultuurvormen werden aangewend om tastbaar te maken wat de oorlog met de Bosnische maatschappij heeft aangericht, en om te beschrijven wat een (mentale en/of fysieke) terugkeer naar Bosnië vandaag kan betekenen. Is het mogelijk terug te keren naar iets wat fundamenteel van gedaante is veranderd? Maar ook: is het mogelijk het land van iemands kindertijd echt te verlaten, zelfs als men het ontvlucht? Deze vragen stonden centraal in de prachtige ruimten van het cultuurhuis De Studio, waar we de hele namiddag en avond gehuisvest waren.

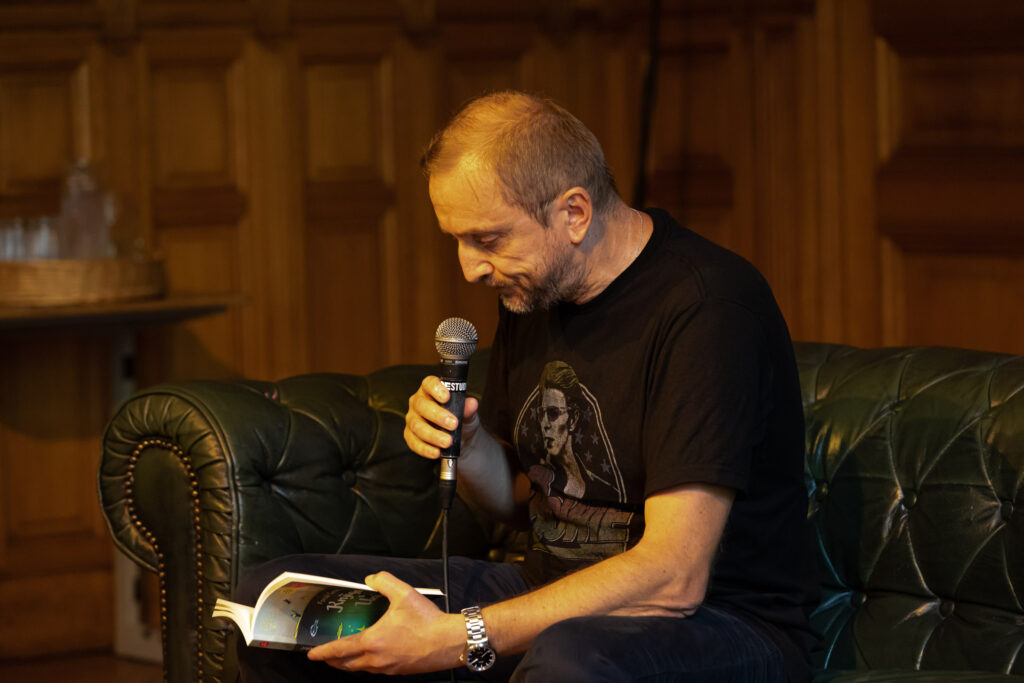

Nadat VRT-journalist Stefan Blommaert vanuit zijn jarenlange ervaring in Oost-Europa op zoek was gegaan naar de gelijkenissen tussen de Bosnische oorlog en de huidige oorlog in Oekraïne, lazen twee Bosnische auteurs in hun eigen taal – of die Bosnisch dan wel Servo-Kroatisch wordt genoemd, vonden zij allebei onbelangrijk – voor uit eigen werk. Behalve de eerder genoemde Lana Bastašić met Vang de haas was dat ook Faruk Šehić, die al in 2013 zijn poëtische debuutroman Zachtjes stroomt de Una afleverde. Na het voorleesmoment volgde een dubbelinterview met beide auteurs, die vanuit zeer verschillende perspectieven over dezelfde thematiek schrijven: enerzijds iemand die tijdens de Bosnische oorlog als jongeman in het Bosnische leger heeft gediend, die zichzelf als Bosniak identificeert, en die ook na de oorlog Bosnië niet heeft verlaten; anderzijds een vrouw die als Servische in Kroatië is geboren, maar die de oorlog als kind heeft beleefd in het voor haar veilige Banja Luka, dat toen de hoofdstad van de Republika Srpska werd, en die sinds 2010 buiten Bosnië heeft geleefd. Ondanks deze grote verschillen bleken beide schrijvers een verrassend gemeenschappelijke missie te koesteren in verband met hun schrijverschap. Ze beschouwen zich allebei als politieke schrijvers tegen wil en dank, precies omdat ze vrij van alle nationalistische mythevorming over de Bosnische oorlog (moeten) schrijven. Schrijven over de oorlog betekent voor hen allebei onherroepelijk ook het schrijven over het voor en het na, en over de haast absolute breuk die “nulpunt 1992” heeft veroorzaakt. Beiden gaven ook aan meer Joego-nostalgisch te zijn dan de hoofdpersonages van hun roman, al was het maar omdat ze in Joegoslavië hun buren gewoon als mensen konden zien, en niet als leden van een etnische groep.

Nog een ander perspectief op de oorlog en zijn gevolgen werd geboden in de documentairefilm Pretty Village. Daarin keert Kemal Pervanić, overlevende van het concentratiekamp van Omarska, terug naar Kevljani, een dorp in Noord-West-Bosnië waar hij zijn jeugd heeft doorgebracht. Hij vertelt zijn eigen verhaal, maar laat ook mensen aan het woord die na de oorlog naar het dorp zijn teruggekeerd. Bovenop de rouw om hun overleden familieleden komt bij velen van hen de angst voor de daders, die ongestraft hun levens in de buurt verder leiden. De confrontatie van Kemal met zijn gewezen leerkracht, die in het kamp van Omarska zijn ondervrager was geworden, toont bijzonder krachtig de blijvende littekens van de oorlog.

Het immense leed van de oorlog vraagt om betekenisvolle en verbindende vormen van rouw. Aida Šehović, een kunstenares die in Banja Luka geboren is maar als vluchteling in Turkije, Duitsland en de Verenigde Staten terechtkwam, nam ons mee in de zoektocht die ze vijftien jaar lang heeft ondernomen naar een dergelijke rouwvorm. Ze vertelde over Što te Nema, een participatief en nomadisch kunstproject waarbij ze tussen 2006 en 2020 samen met een grote groep vrijwilligers op iedere verjaardag van de genocide in Srebrenica voor elk van de 8372 dodelijke slachtoffers op een publieke plaats een kopje koffie uitschonk. In 2020 raakten deze kopjes voor de eerste keer de grond in Srebrenica zelf, en een jaar later keerde ook Šehović zelf – in de tegenstroom – terug naar Bosnië. Ze vertelde over de vele duurzame contacten die dankzij dit artistieke project werden gesmeed, maar ook over de redenen waarom ze een uitnodiging om het project ook in Belgrado op te stellen, heeft afgeslagen. Zo’n project kon immers onterecht geïnterpreteerd worden als een bewijs dat de Servische maatschappij heeft afgerekend met de heersende cultuur van ontkenning.

Sporen van die cultuur van ontkenning in de Bosnisch-Servische samenleving konden ook opgevangen worden in Retour à Višegrad, de recente documentairefilm waarin de Franse filmmaakster Julie Biro een gewezen schooldirecteur en de weduwe van een gewezen leerkracht volgt in hun poging om een klas uit 1992 weer verenigd te krijgen – hoewel de Bosniakken in dat jaar de stad hadden moeten verlaten . Bij een beperkt aantal Bosnische Serviërs is twijfel hoorbaar, en één van hen weigert zelfs te komen. Toch toont Biro’s film vooral dat een dergelijke klasreünie wel mogelijk is, en dat zij helend kan werken voor alle deelnemers.

Volstaan dergelijke kleine signalen om toch enige hoop te kunnen koesteren voor de toekomst van Bosnië-Herzegovina? Het was één van de vragen die aan bod kwamen in het afsluitende debat, dat gemodereerd werd door Stefan Blommaert. Dat er kunstenaars en kleine groepen activisten bestaan die de paralyserende (en potentieel moordende) logica van het etnisch nationalisme proberen te doorbreken werd door de deelnemers aan het gesprek als een teken van hoop gezien. Daar staat echter tegenover dat de door het Dayton-akkoord gecreëerde systeem belet dat deze maatschappelijke beweging zich ook omzet in politieke verandering, en dat ook de internationale gemeenschap te weinig bekommerd is om de Bosnische situatie.

Het hart van Europa – waar katholicisme, orthodox christendom en islam elkaar ontmoeten, waar grote rijken elkaar hebben opgevolgd en waar met de meest diverse ideologieën is geëxperimenteerd – is ook vandaag nog diep geschonden. Maar we hebben het tijdens dit cultuurfestival wel heel duidelijk horen kloppen.

The Violated Heart of Europe. A Festival of Art, Literature and Film about Bosnia-Herzegovina

Antwerp, The Studio, 18 May 2022

Some impressions

“Driving through Bosnia requires a different dimension: a twisted, cosmic wormhole that doesn’t take you to a real, external goal, but into the gloomy, barely traversable depths of your own being.” Sara, the fictional protagonist of Lana Bastašić‘s overwhelming debut novel Catch the Rabbit, comes to that unenlightening conclusion as she drives across the country with her former childhood friend Lejla, in search of the latter’s brother who disappeared during the war.

During the cultural festival The Violated Heart of Europe, which Power in History organised in cooperation with UCSIA on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of independent Bosnia and Herzegovina, the keynote was neither one of great optimism. How could it be otherwise? The country was born in the midst of a bloody war that has left deep scars to this day. Approximately one hundred thousand Bosnians died as a result of the war and many more fled the country. Bosnian society, in which Muslims, Catholics, Orthodox Christians, Jews, Roma and atheists had lived side by side for ages, was brutally shattered. In the war’s aftermath a complex political constellation was created in which ethnicity became an all-important factor. The outcome of the ethnic cleansing that had taken place was largely confirmed by the Dayton Agreement of December 1995. That agreement confirmed the existence of a semi-autonomous Serbian Republic within the Federal Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The fact that the political elites of this Republika Srpska are today attempting to withdraw from the Bosnian institutions shows how uncertain the situation still is. In this context, for many Bosniaks – Bosnians who identify with the Islamic tradition – the war in Ukraine is a fundamentally traumatising experience, which is brutally reopening their barely healed wounds.

And yet, during The Violated Heart of Europe, there was also a lot of room for beauty, warmth, connection and even a little hope. Various cultural forms were used to make tangible what the war did to Bosnian society, and to describe what a (mental and/or physical) return to Bosnia can mean today. Is it possible to return to something that has fundamentally changed shape? But also: is it possible to really leave the land of one’s childhood, even if one flees it? These were the core questions evoked in the inspiring setting of the culture house De Studio, where we were accommodated the whole afternoon and evening.

After VRT journalist Stefan Blommaert had Shared his long experience in Eastern Europe to look for similarities between the Bosnian war and the current war in Ukraine, two Bosnian authors read from their work in their own language – whether it is called Bosnian or Serbo-Croatian is unimportant to them both. Apart from the aforementioned Lana Bastašić with Catch the Rabbit, this was also Faruk Šehić, who in 2013 delivered his poetic debut novel Quiet flows the Una. The reading moment was followed by a double interview with both authors, who write about the same theme from very different perspectives: on the one hand, someone who served in the Bosnian army during the Bosnian war as a young man, who identifies as a Bosniak, and who has not left Bosnia even after the war; on the other hand, a woman who was born in Croatia as a Serb, but who experienced the war as a child in Banja Luka, which for her was safe and became the capital of Republika Srpska – and who has been living outside Bosnia since 2010. Despite these major differences, both writers turned out to have a surprisingly common mission in relation to their writing. They both see themselves as political writers against their will, precisely because they (have to) write about the Bosnian war independently of all nationalistic myths. Writing about the war for both of them irrevocably means writing about the before and after, and about the almost absolute rupture caused by “zero point 1992”. Both also indicated that they were more Yugo-nostalgic than the main characters of their novel, if only because in Yugoslavia they could see their neighbours simply as people, and not as members of an ethnic group.

Yet another perspective on the war and its consequences was offered in the documentary film Pretty Village. It relates how Kemal Pervanić, a survivor of the Omarska concentration camp, returns to Kevljani, a village in north-western Bosnia where he spent his youth. He tells his own story, but also lets people speak who returned to the village after the war. On top of the mourning for their dead relatives, many of them fear the perpetrators, who pursue their lives in the neighbourhood with impunity. Kemal’s confrontation with his former teacher, who had become his interrogator in the Omarska camp, shows the lasting scars of war particularly powerfully.

The immense suffering of war calls for meaningful and connecting forms of mourning. Aida Šehović, an artist who was born in Banja Luka but ended up as a refugee in Turkey, Germany and the United States, made us of her fifteen-year search for such a form of mourning. She told us about Što te Nema, a participatory art project in which, on every anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide between 2006 and 2020, she and a large group of volunteers poured out cups of coffee in a public place – one cup (called a fildžan) for each of the 8372 deadly victims. In 2020, these cups touched the ground for the first time in Srebrenica itself, and a year later, Šehović herself returned to Bosnia – in the counter-current. She told about the many lasting contacts that were forged thanks to this artistic project, but also about the reasons why she turned down an invitation to set up the project in Belgrade. After all, such a project could be wrongly interpreted as proof that Serbian society has dealt with the prevailing culture of denial.

Traces of this culture of denial in Bosnian Serb society are also encountered in Retour à Višegrad, the recent documentary film in which the French filmmaker Julie Biro follows a former school director and the widow of a former teacher in their attempt to reunite a class from 1992 – although the Bosniaks had to flee the town that year. Doubts can be heard from a limited number of Bosnian Serbs, and one of them even refuses to come. Yet Biro’s film mainly demonstrates that such a class reunion is possible, and that it can have a healing effect for all participants.

Are such small signals enough to allow some hope for the future of Bosnia and Herzegovina? This was one of the questions discussed in the closing debate, moderated by Stefan Blommaert. That there are artists and small groups of activists who try to break through the paralysing (and potentially murderous) logic of ethnic nationalism was considered by the participants in the discussion as a sign of hope. On the other hand, however, the system created by the Dayton Agreement prevents this social movement from translating its agenda into political change, and the international community is not sufficiently concerned about the Bosnian situation either.

The heart of Europe – where Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity and Islam meet, where great empires have succeeded each other and where the most diverse ideologies have been experimented with – remains deeply violated even today. But we heard its beating very clearly during this festival of culture.

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar kim.overlaet@uantwerpen.be.