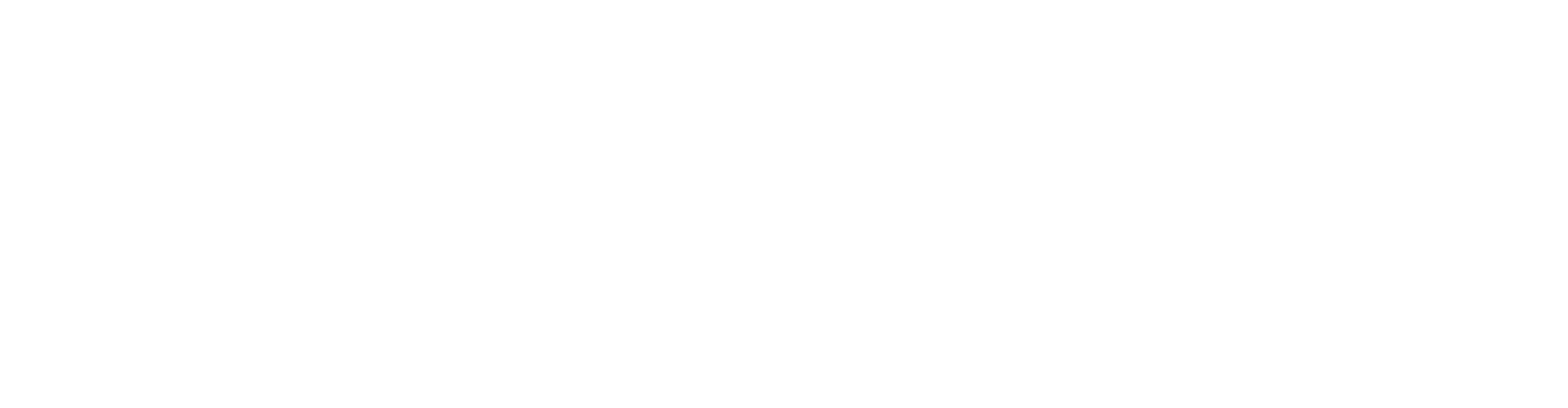

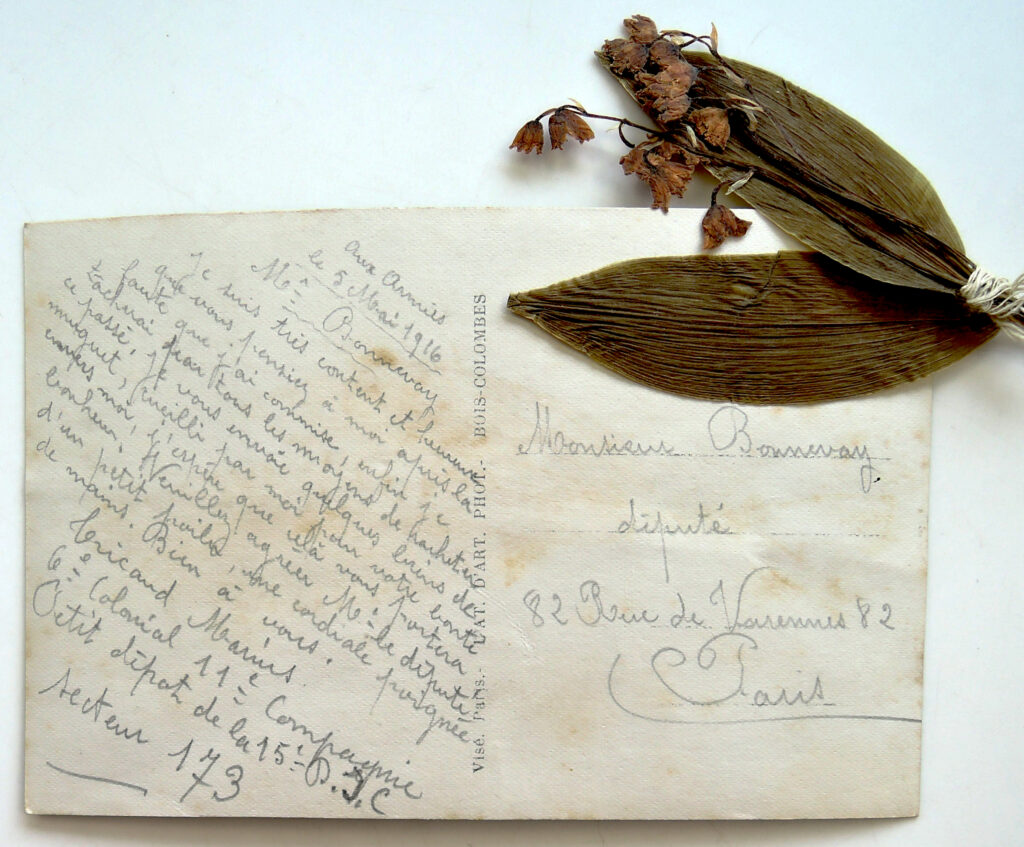

On 5 May 1916, Frenchman Marius Tricaud added a small bouquet of lilies-of-the-valley to a postcard that he sent to the Parisian address of “his” representative in parliament, Laurent Bonnevay (député du Rhône). What was the purpose of this action and how does it nuance the clientelist quid pro quo nature that is said to have characterized exchanges within the French Third “Republic of comrades” and “Republic of lawyers”?

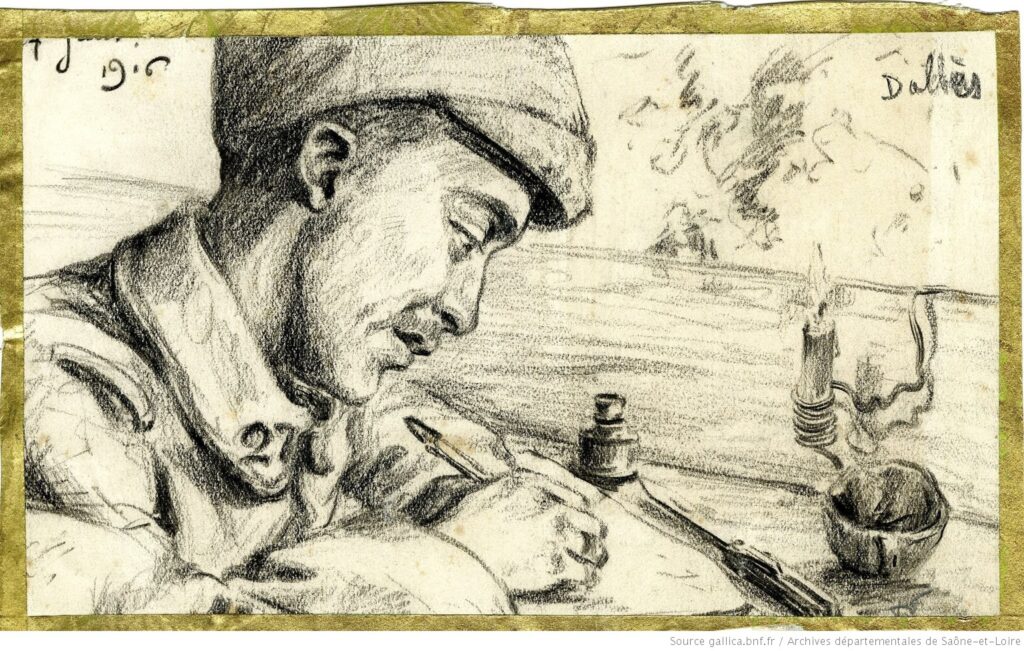

In his capacity as a voter in the second constituency of Villefranche-sur-Saône in the Rhône-department, Tricaud seems to have experienced a close connection with his parliamentary representative, on which he continued to build throughout his war correspondence. As a young male citizen, Tricaud was drafted into the French army at the Western front during the Great War. On 1 October 1915, he contacted Bonnevay to inform him of how they had managed to win the day against the boches. Despite the injury that he had contracted in battle, he was motivated (“burning with desire”) to avenge his less fortunate comrades. The familiar tone of this particular letter (signed: votre petit Poilu) gave Bonnevay the opportunity to act betrayed, five months later, when he learned about Tricaud’s desertion. While the man’s first letter had made him proud, the second one disappointed him. In that particular letter, which Tricaud sent from military prison on 6 March 1916, he asked his parliamentary representative to defend him as his lawyer before the court-martial. Although, to a present-day reader, such a question seems completely out of place, it was not uncommon for Bonnevay and his peers with a degree in law to receive requests for legal representation in very personal cases. Indeed, Bonnevay belonged to the 28 to 29 percent of deputés of the early twentieth century who had successfully completed their legal studies. How “ordinary” citizens such as Tricaud mobilized the image of a deputy-lawyer in their letters differs from one député to the other, depending on how the latter used to present himself towards his constituents and towards his peers in parliament. Still, there was at least one common denominator in the deputies’ responses: as they tried to avoid conflicts of interest, they passed such individual matters onto a befriended lawyer. In doing so with Tricaud’s desertion case, Bonnevay allowed himself to take a step back and reprimand the man instead. By asking: “How could you have acted like this? Have you deceived me then?” he expressed his fatherly disillusion. He hoped that Tricaud would have the right attitude and ask the court for permission to go back to the warzone to make up for his mistake. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the deputy seemed genuinely interested in the soldier’s fate. A letter from lawyer Falconnet from Lyon shows Bonnevay’s engagement in “ensuring the defense of the unfortunate Tricaud.”

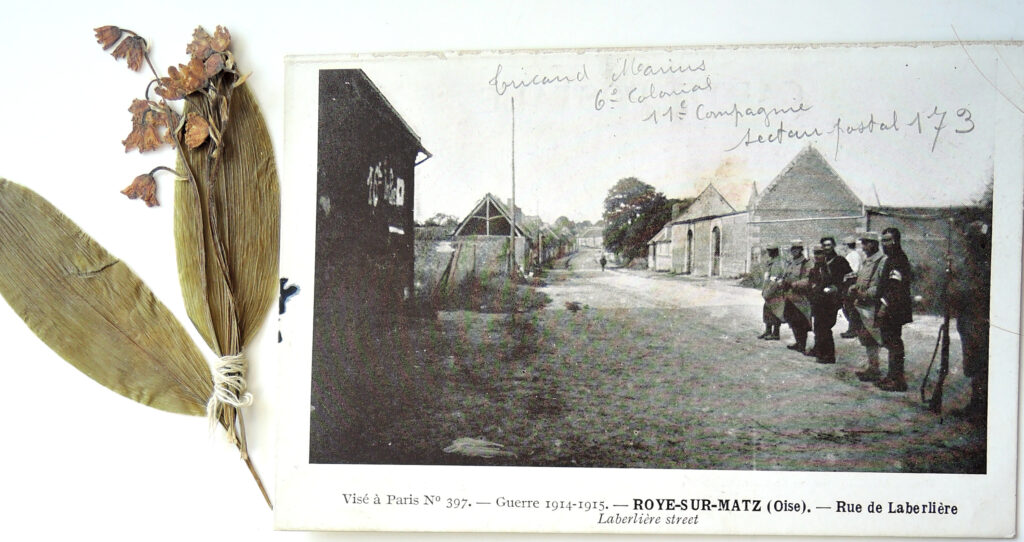

After the trial, the soldier acknowledged the député’s involvement via a small note of thanks in which he explicitly identified himself and his partner as Votre petit électeur et sa petite fiancée. Although he indeed belonged to Bonnevay’s electorate, their communication, rather than revealing a mere quid pro quo exchange, showed one that was characterized by moral guidance. While, a couple of days later, Tricaud claimed that he was happy to be back in service so that he could redeem himself from the stigma of a coward and deserter, he still hoped to receive letters from the député, from time to time, as a form of encouragement. He accepted Bonnevay’s fatherly advice, asked him for forgiveness, and thanked him for ensuring his legal representation, which the deputy, in his turn, justified by bringing up Tricaud’s past courage. Under the condition that the soldier would continue to exhibit such good behavior, Bonnevay promised his future support. As a token of his gratitude for the député’s kindness, Tricaud sent him lilies-of-the-valley from the warzone, hoping that these would bring him luck. The dried flowers have been preserved in good condition, along with Bonnevay’s incoming war correspondence, testifying to the importance the député himself too attached to these exchanges.

Whereas the physical presence of the flowers added an exceptional dimension to the otherwise common practice of writing letters to Third Republican deputies of the Chamber, the negotiated relationship of proximity (between citizen and député) that the flowers represented was far from unusual. In its extreme form, the letter-writers’ image of their connection could even take sacralized proportions, to the point where their correspondence can be seen as an expression of political religion. Via an analysis of such letters to four individual French representatives in parliament between 1900 and the 1930s, my recent book Ordinary Citizens and the French Third Republic seeks to offer new insights into these citizens’ lived experiences with political religion, republicanism and secularization, democratization without full citizenship, and tensions between left and right, governance and representation, clientelism and politicization. In other words, I explore the paradoxes of the French Third Republican regime and how these were (re)imagined by “ordinary” men and women facing rapidly succeeding governments, the Great War, the subsequent economic crisis, political scandals, anti-parliamentary sentiments, and changes in electoral laws that nonetheless still denied women the vote. Helping readers to reflect on the nuances of the politicization process, the book is aimed towards those researching French political history and modern European political culture.

Blog post by Karen Lauwers, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki (2019–till date) and former PoHis-affiliated PhD-candidate at the University of Antwerp (2014–2019)

Do you want to know more about the political identities that ordinary men and women in early-twentieth-century France construed for themselves and their representatives? Find my book here: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89304-0

Do you want to know more about the materiality and sound of these negotiation processes? Listen to the first episode of the “CALLIOPE Speaks” podcast here: https://www2.helsinki.fi/en/researchgroups/vocal-articulations-of-parliamentary-identity-and-empire/calliope-podcast.

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar kim.overlaet@uantwerpen.be.