A quarter of a century ago, Diana, Princess of Wales (1961–1997) walked through a minefield in Angola. Her seemingly effortless stroll drew the world’s attention to the crippling legacy of decades of civil war. Film stars – the royalty from the other side of the Atlantic – and kindred special envoys of the United Nations have followed her example to alert us to other humanitarian crises. Images of a person of privilege surrounded by peril or abject misery appeal to our conscience and solidarity. As such they constitute tools of power.

Fast backward to four centuries ago. Accompanied by a handful of ladies-in-waiting, the Dowager-Archduchess Maria of Inner Austria (1551–1608) sat down for a frugal lunch with a community of cloistered nuns in Graz. Her exquisite clothes and expensive jewellery clashed with the austere and at times worn-out garbs of her hosts. Once the meal was over, she got up, put on an apron, and did the dishes. Soon word of her exemplary piety and humility spread beyond the walls of the convent, strengthening her authority within the dynasty as well as beyond.

At first glance the two gestures appeared totally unrelated. What united them, however, is the way they spoke to the political communities of their times. Living in an age of mass politics, Diana used the media to reach out to the population at large. Her message concerned the devastating reverberations of civil war. Maria addressed a much narrower constituency that only took a privileged elite into account. For them, the confrontation between Protestantism and Catholicism was among the most pressing issues of the times.

No two early modern institutions seemed further removed from each other than the court and the cloistered nunnery. The court stood at the apex of society. Its splendour was designed to secure the authority of the dynastic state by overawing its subjects. Having “a foot in the palace” allowed members of the nobility to seek political influence. It could bring them and their relatives status, privilege and patronage, which translated into offices, commands and benefices, even an advantageous marriage. All of this was the opposite of a life vowed to chastity, poverty and obedience, particularly for those orders, such as the Poor Clares or the Discalced Carmelites, that were strictly contemplative. Locked away behind bars in accordance with the decrees of the Council of Trent, their communities physically as well as mentally turned their backs on the world. Or at least they tried to. In her study of the convents of early modern Valladolid Elizabeth Lehfeldt has demonstrated how established roles and societal expectations repeatedly sought ways to circumvent the strict enclosure of the nuns.

Habsburg women were fascinated by these nunneries. Between 1559 and 1628, an empress, three queens, two infantas and a succession of archduchesses founded a monastery in which they reserved a royal apartment for themselves. It consisted of a suite of rooms astride the cloistered and the freely accessible areas of the building, allowing them to pass from one to the other. Some of the foundresses took to living there with a small household. They did not take vows. Every now and then they would return to the palace and participate in the life of the court. Others just used the rooms when they came to visit the nuns.

Contemporary sources depicted these foundations as acts of profound piety. More recently, María Leticia Ruiz Gómez has argued that these convents “provided shelter for leading women of the Habsburg dynasty when they had lost or forsaken the roles for which they had been destined”. Implicitly, this view draws on the stereotype that the sole destiny of female members of a dynasty was to make a politically advantageous marriage and produce offspring. Once they had performed that mission or if they had failed to do so, they could only withdraw from the world and pray for the dynasty’s continuity and success. This view does not sit well with our growing understanding of dynasties as complex organisations in which women as well as men could assume a number of different roles. Based on her study of the archetype of these foundations, the Descalzas Reales in Madrid, Magdalena Sánchez has demonstrated that taking up residence in one of these monasteries did not put an end to the political influence that these women could exercise. Their relatives would often visit them or even stay over. In some cases, princelings would receive part of their education there. Ambassadors requested an audience in the hope of persuading the royal residents to intercede on their behalf. Rather than depriving them of their political clout, living among reputedly saintly nuns actually gave a boost to their charisma. As such, founding such a monastery was a means of empowerment for a Habsburg woman.

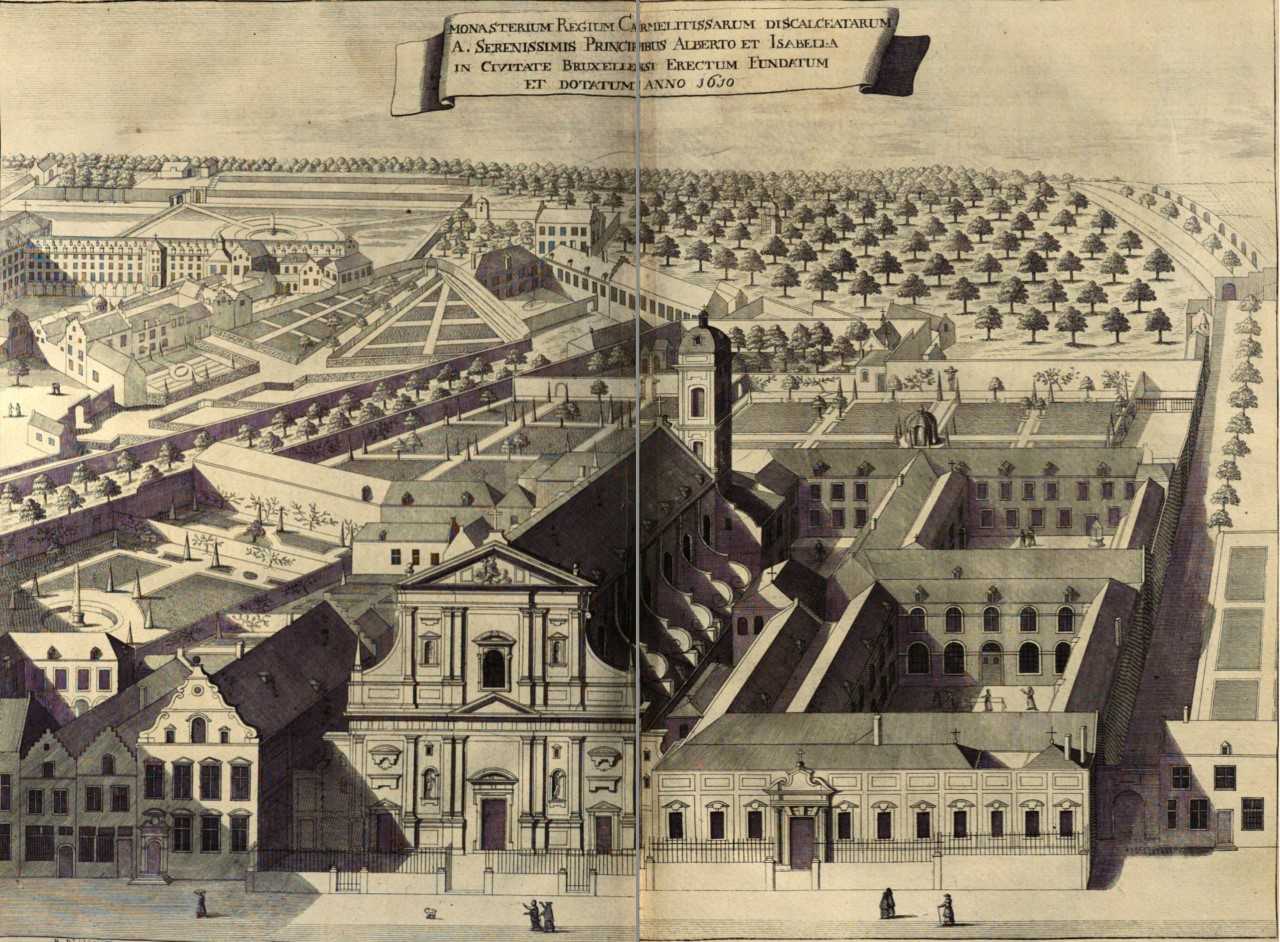

The convivencia – an expression coined by Ana García Sanz to typify the living together of the court and the cloister – proved a mixed blessing for the nuns. On the one hand royal patronage gave them a stable financial foundation, one that mendicant orders could normally not take for granted. At the same time, however, it could easily become overwhelming. Speaking of the Royal Carmel founded by the Archdukes Albert and Isabella in Brussels in 1607, the then superior, Madre Ana de Jesús, wrote: “Here, it is a lot of work to be the porter, because the house is so big. As it is a royal foundation there is so much to walk around that I say that we lose part of the merit of the enclosure by living on such a grand scale”. Nor was size the whole story. When Emperor Joseph II dissolved the Royal Carmel along with most of the other such monasteries founded by his relatives in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, the commissioners found over 200 paintings decorating its walls, a far cry from the austerity prescribed for the Discalced Carmelites.

Recommended literature:

Ana García Sanz, “Juana de Austria: Un modelo de intervención femenina en la Casa de Austria”, in: María Leticia Sánchez Hernández, ed., Mujeres en la Corte de los Austrias: Una red social, cultural, religiosa y política, La Corte en Europa: Temas, 14 (Madrid: Ediciones Polifemo, 2019) 259–268.

Katrin Keller, Erzherzogin Maria von Innerösterreich (1551–1608) : Zwischen Habsburg und Wittelsbach (Vienna: Böhlau, 2012).

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt, Religious Women in Golden Age Spain: The Permeable Cloister (Farnham: Ashgate, 2005).

María Leticia Ruiz Gómez, “Princesses and Nuns: The Convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid”, Journal of the Institute of Romance Studies, 8 (2000) 29–46.

Magdalena S. Sánchez, “Where Palace and Convent Met: The Descalzas Reales in Madrid”, Sixteenth Century Journal, 46 (2015) 56–58.

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar kim.overlaet@uantwerpen.be.