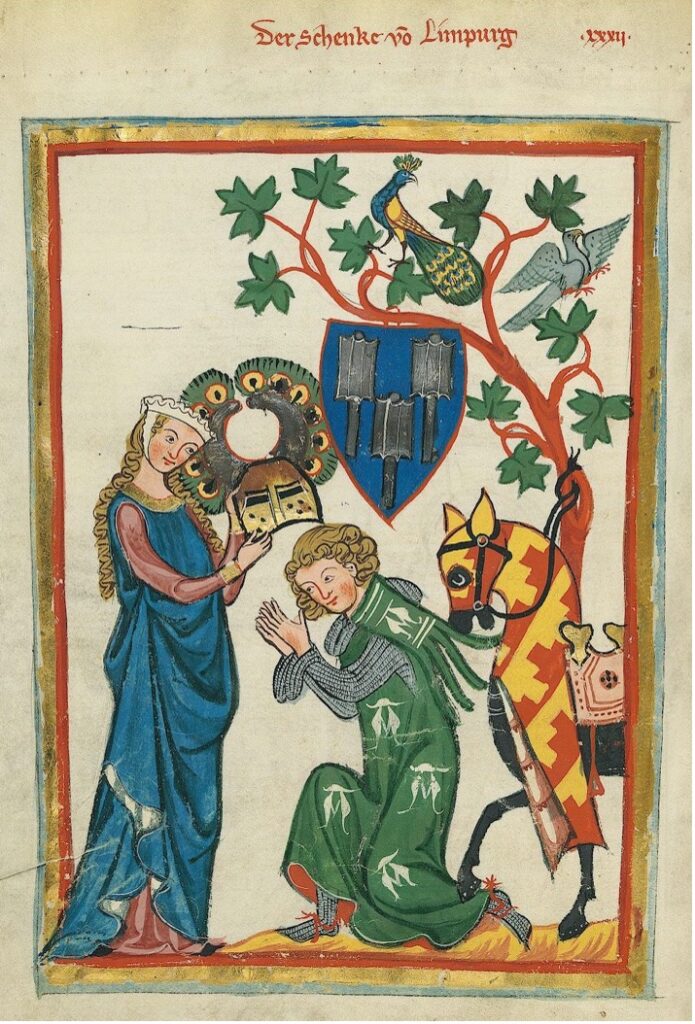

Figure 1 Bertrandon giving a Latin Translation of the Koran to Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy. Illustration by Jean Le Tavernier (1455), Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF).

Mountainous pathways and sand dusting up around him. After a two day ride on horseback, Bertrandon de la Broquière, a high noble office-holder at the court of the Burgundian duke Philip the Good, approached the city gates in Damascus in 1432 with his travel companions and Arabic guide: “…at the entrance of Damascus, we encountered X or XII Saracens; and because I wore a large felt hat, which is not the custom yonder, there was one with a very short baton (who) swung it over and stole it from my head. I raised my fist to punch him, but my guide got between the two of us…I say this as a warning that there is no need to quarrel with them (the Saracen guard) because they seem to me to be mean people with little reason…”

This fascinating passage of a nobleman’s journey to the Near East implicitly demonstrates how defending one’s honour – as noblemen ought to do even in such foreign circumstances – implies particular expressions of medieval masculine behaviour and social status. When masculine performances were retained or restricted, the passage also reveals how Bertrandon explains the absence of his defence by falling back on a gendered discourse. According to the chivalric ethos, the normative form of (elite) masculine behaviour, a true knight must choose his battles wisely – a code Bertrandon is all too familiar with. Consequentially, our nobleman justifies not (physically) reacting to the insult through deploying a stereotypically unmanly representation of the Islamic Other in his narrative, implicitly representing the guard as an unworthy opponent.

Inspired by such insightful incidents like Bertrandon’s encounter with Saracen guards, I pivoted my research angle to take a closer look at the masculine performances and discourses of Western aristocratic travellers. Yet, anno 2022, it is quite striking how historians working on the medieval period – like myself – still seem to be confronted with legitimising why one would choose gender, particularly masculinity, as a research perspective to find new meanings to frequently studied sources, such as travel narratives. During a productive conversation over a glass of chardonnay or two, colleagues expressed their concerns and asked whether there was any gender to be found in late medieval travel narratives at all – especially considering few medieval travel narratives written by female authors withstood the test of time. Furthermore, colleagues reminded me that little information on the perception of women was to be found in these sources. This informal exchange between peers unconsciously reflected how various medievalists still look at gender studies.

My experience does not seem to be an isolated one. According to Patricia Skinner, gender studies in the medieval period is still not whole-heartedly accepted. Skinner argues that the majority of gender historians opt to research the nineteenth and twentieth century as women’s emancipation slowly took more form. Medievalists, in turn, sometimes struggle to find gendered utterances in medieval narratives, as they tend to look at their source material through modern spectacles, temporarily forgetting to customise their lenses to the medieval language.

However, my own experiences show that one of the main reasons why gender history is still not fully anchored into the academic debate is the systematic assumption that gender history solely analyses women. Additionally, for many scholars, sources containing more religious information do not seem to give enough inside into gender. Yet, when being convinced how these extraordinary travel narratives not only reveal information about foreign landscapes and societies but also reveal specifics about the author-traveller’s own world view and their own social-cultural identity, how can one not see…gender?

Let’s call in the help of our friend Bertrandon.

Several historians have focussed their attention on either the military aspect of his journey to the East – his travel was after all an espionage mission in favour of the crusading agenda of his master, the Burgundian duke – or on his progressively tolerant attitude towards the Islamic Other he met along his voyage. Yet, what I have not read in specialising literature so far is how his travel account is littered with references and reflections of chivalric conduct both on a performative and a narratological level. One of the most well-known characteristics of chivalric conduct is the display of courageous actions, and the absence of fear – along with honourable behaviour as mentioned above. When describing his passage of the Mont Cenis, a massif bordering France and Italy, Bertrandon flaunts his brave self when he crosses the Alps by emphasising the high and dangerous altitudes and distinctly mentioning what to do to avoid risks of avalanches. What he does not mention is the matter of fear, like a true knight ought to do. The same can be said for the perilous sea journey from Venice over the Adriatic to Jaffa, the port of Jerusalem. In contrast to other pilgrims who fearfully mentioned the storms and occasional shipwrecks, Bertrandon once again remains silent.

Still, more straightforward is the reasoning he writes to legitimise his decision to continue his travels through the Mamluk and Ottoman Empires alone, against his friend’s advice. He writes, quite modestly: “And to my understanding, which I do not say is certain, it seems to me that a man well enough composed to endure pain and medium strength, and he has money and health, that all things are possible for him to do.” Not only does he frame his decision as a chivalric quest, but he also visibly states his opinion on what men of his status and stature can achieve.

To me, this surely brings gender back to the medieval. How about you?

Recommended literature:

– P. SKINNER, Studying gender in medieval Europe. Historical Approaches, New York : Palgrave Macmillen, 2017.

– A. TAYLOR, ‘Chivalric conversation and the denial of male fear’, in J. MURRAY (ed.) Conflicted identities and multiple masculinities. Men in the medieval West, New York : Routledge, 1999.

Citations Bertrandon de la Broquière:

« Et à mon entendement, lequel je ne dis point qu’il soit sçeur, il me semble que à un homme assez bien complectionné pour endurer peyne et de moyenne force, mais qu’il ait argent et santé, que toutes choses luy sont possibles de faire. » C. SCHEFER (ed.), Le voyage d’outremer, p. 110.

“Et à l’entrée de Damas, nous vindrent incontinent regarder X ou XII Sarazins; et pour ce que je portoye ung grant chappeau de feutre qui n’est point la coustume de par delà, il y en a eu ung qui a tout ung court baston le fery pardessus et me le fist voler hors de la test. Je hauchay le poing pour le ferir, mais mondict moucre se mist entre deux…Je dis cecy pour advertir qu’il n’est point besoin d’avoir debat à eux, car ilz me semblent meschans gens et de petite raison…” C. SCHEFER (ed.), Le voyage d’outremer de Bertrandon de la Broquière, premier écuyer tranchant et conseiller de Philippe le Bon, duc de Bourgogne, Paris : Ernest Leroux, 1892, p. 118.

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar kim.overlaet@uantwerpen.be.