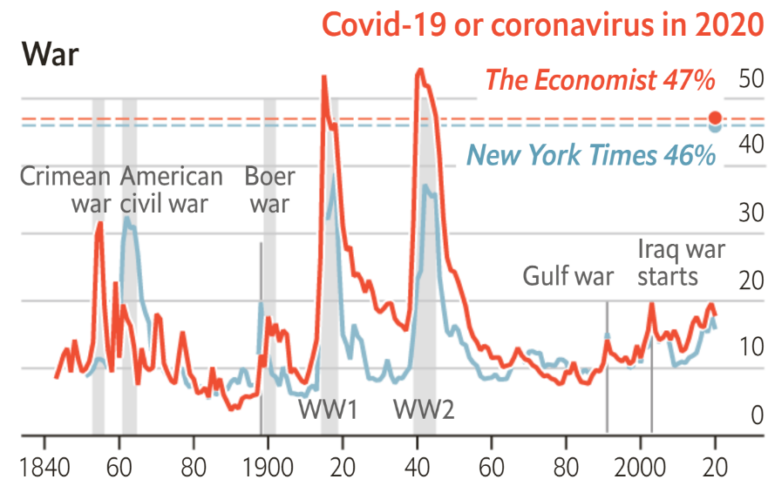

Politicians and pundits regularly call the current Corona pandemic the biggest crisis since World War 2. A few months ago, the Economist reinforced this metaphor by analyzing their entire archive of articles since the magazine’s inception in 1843.

The Economist found that no less than 47% of all articles written in 2020 were related to the coronavirus (see figure 1, red line). There are only two events in the history of the magazine that received more attention: World War 1 and World War 2. For the New York Times, the situation is even more striking: the Covid-19 pandemic is the most covered issue in the history of the newspaper (blue line in figure 1).

Unequal impact

It might be no surprise that almost half of what journalists write these days is Corona-related. The Corona pandemic is a major public health crisis with millions of casualties, an economic crisis that leaves tens of millions unemployed and a social crisis that impacts everyone.

However, it is important to keep in mind that the pandemic has a very unequal impact on different industries, companies and individuals. While many, predominantly small, business lost large fractions of their sales other, predominantly large, firms broke revenue records.

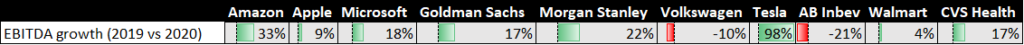

Table 1 shows the growth in EBITDA (a metric of the operating profitability of a company) for a selection of large companies between 2019 and 2020. Technology firms like Amazon or Microsoft saw their EBITDA rise by double digits during the pandemic. Even the EBITDA of Apple, a firm with relatively expensive products which consumers might be less likely to buy during a major catastrophe, rose significantly. Large investment banks like Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs had a wonderful 2020 as well.

V-shaped or U-shaped?

Overall, in the U.S. 45 of the 50 biggest firms were profitable during the largest crisis since WWII. This is good news for the economy, but it stands in sharp contrast to how most individuals experienced the pandemic.

When nations first went into lockdown in March last year, economists argued about what the subsequent economic recovery would look like (see figure 2). Many were wishing for a V-shaped recovery. This would mean that we can put our economy in the fridge for a few weeks during lockdown, and quickly bounce back to previous levels once the restrictions were lifted. Others feared a U-shaped recovery: our economy would partly rot during lockdowns as people lose their jobs and companies go out of business. As a result, it would take longer before we are back up to speed.

K-shaped recovery

Today, we mostly see a K-shaped recovery: a part of the economy quickly recovers, and sometimes even performs better than ever (big tech firms for example), while other industries do not recover at all (tourism for example). Or as John Donahoe, the CEO of Nike, put it: “these are times when the strong can get stronger”.

“For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” (Matthew 25:29)

If we look at people instead of companies, we can see the K-shaped recovery as well. Consider the following facts:

- Billionaires saw their wealth rise by 44% during 2020.

- Employment rates of high wage employees are back to pre-Covid levels, while employment rates for low wage employees are still 28% lower.

- Belgians saved 23 billion euro more in 2020 compared to other years. Needless to say that these additional savings where not equally distributed across the population.

In summary

A K-shaped recovery is partly good news as many industries are performing very well. On the other hand, many companies and individuals have a very hard time catching up. Policy makers should be vigilant not to leave large fractions of our economy behind.

This blog is a summary of the ‘Corona & Onze Economie: Wat Nu?’ lecture, hosted by student association Wikings NSK and alumni organisation Alechia VZW.