Due to global lockdowns and the fear of going to physical stores, consumers are purchasing more goods online. In Belgium, several parcel and last mile couriers have reduced their capacity for eCommerce stores because of the large number of orders, too few couriers and a lack of sorting capacity. But the biggest issue these days is the switch in the types of products consumers order online.

In ‘normal’ times, people mainly buy (small) electronics, toys, small furniture, fashion items, etc, online. Since the start of the lockdown however, other categories have become popular: do-it-yourself products, larger toys, garden and home furniture, cleaning products and food. In general, these products are larger and heavier than the average package before the corona crisis. Can B2C last mile providers (responsible for the last part of the journey, from the distribution center to the customer) handle this?

The sorting process

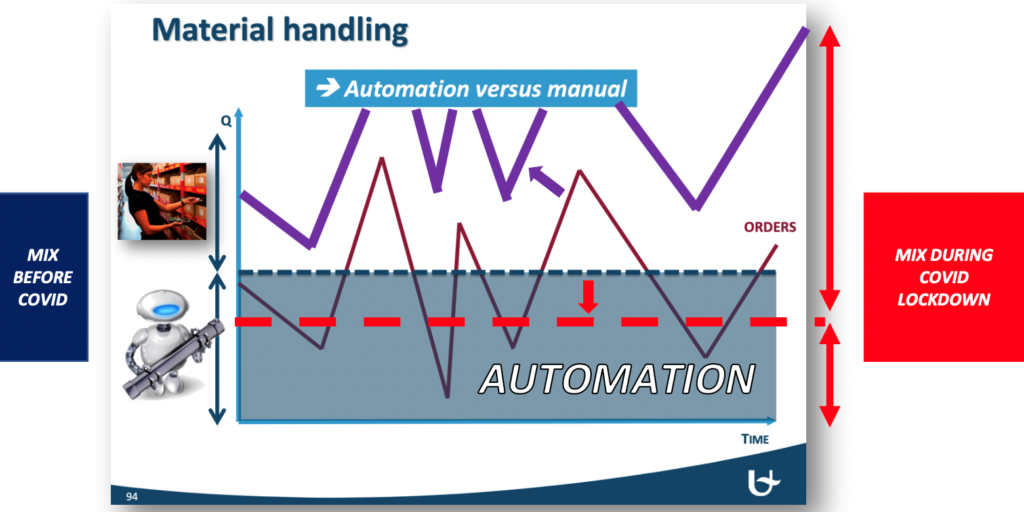

Even more so than traditional B2B logistics players such as DHL, TNT-FedEx and UPS, B2C last mile providers have strongly relied on local parcel sorters (Bpost, PostNL, DPD, GLS) in the past decade. Their automated sorting system – the conveyor belt – is usually designed based on an expected mix of small, medium and large packages: a large share of small and medium packages (<10 kg) and a small share of larger packages (> 10 kg). The more this is deviated from, the slower the sorting process will be.

“It makes sense that more small packages fit on a conveyor belt, compared to larger ones. In addition, the belt runs slower when it has heavy packages on it. In other words, the more large packages, the less that can be processed.”

Push and pull

But why can’t we cope with this peak in online purchases during this corona crisis? Such peaks aren’t new, if you consider Christmas and Black Friday. The big difference is that package suppliers can prepare for predicted peaks, by hiring temporary workers. In addition, eCommerce stores tend to direct their customers towards small, medium and large purchases through promotions. So even though people buy more, the mix of small, medium and large purchases remains the same.

This is different during the corona crisis. The peak we see today is not the result of push marketing, but of a pull effect from consumers. People now have more time to work in their homes and gardens. For that, they need DIY products, home and garden furniture, etc.

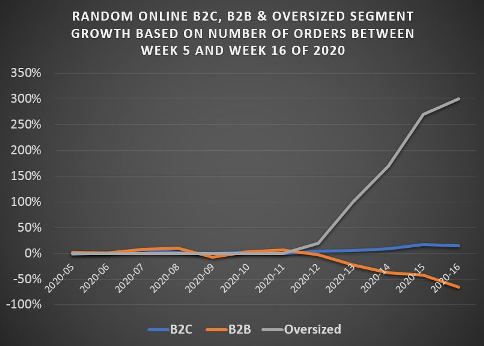

Figure 1: Overview of several random last mile segments over a period that started just before the Belgian lockdown until mid-April (week 16). The orange B2B line is clearly on a downward trend. The blue line with a moderate increase (+/- 25%) shows the order pattern of any B2C flow. The steepest gray line is the growth in online sales orders for a furniture and do-it-yourself product line (oversized products: L + W + H> 300 cm or weight> 30 kg). (source: De Tijd, GFK, Retail Detail, etc. 2020)

Figure 2: An automated transport system has a fixed throughput (the blue dotted line) using manual labor to balance peak volumes. The red dotted line shows the decrease in throughput caused by the lower speed of the conveyor belt due to weight and volume problems. The purple line and arrows indicate the extra manual labor required to handle an increasing number of non-transportable volumes.

Subcontracted drivers

A traditional B2C last mile network is characterized by a low profit margin and an outsourced supply capacity. Most of the last mile players outsource deliveries to small subcontractors – subcouriers – who are paid between 1.5 and 2 euros per successful delivery. Most B2C deliverers ‘drop’ about 80 to 100 packages per route (8 to 10 hours). The average turnover per courier is about 150 to 200 euros per day. With this, they pay all costs (fuel, van/ bicycle, insurance, taxes, etc.).

This is where the problem currently arises. Not only the sorting, but the delivery as well is based on small to medium sized packages. 80 to 100 small to medium sized packages will fit in an average van (VW Transporter, Mercedes Sprinter, etc.). The same cannot be said if those packages are all oversized. The average number of drops will decrease, this means less income per route.

It is therefore not inconceivable that sub-couriers will adjust their prices per drop to keep their earnings in line with their costs. If they don’t, they may go bankrupt. This in turn can lead to a shortage of (good) drivers and thus disrupt the market even further.

Is the end of “cheap” B2C deliveries near?

B2C last mile parcel networks will have to take into account the delicate balance between density and complexity. The trend of more complex parcel delivery has been taking place in recent years. There are countless examples of companies that deal with non-standard parcel delivery, such as PostNL Extra @ Home, Dynalogic, Dockx Select, CoolBlue… This market segment is growing at a stable 5% to 10% per year.

“The COVID consumer buying switch has caused such a shockwave that all B2C last mile package networks will have to rethink their approach. In 2013, I formulated that last mile networks were mainly focused on small and medium-sized packages, but that two segments would have a major impact between 2015 and 2025: fresh food delivery and oversized packages.

Complexity becomes the new focus

In the long term, the low delivery prices of online purchases may disappear. They will rise to the level of the larger logistics players. Traditional B2C last mile players will have to split their packet flows into easy, efficient flows on the one hand and more complex, non-standardized flows on the other. This will affect efficiency, margins, and therefore price.

More information about the research activities of Roel Gevaers and his colleagues can be found on the webpage of the Department of Transport and Regional Economics and C-MAT – Center for Maritime & Air Transport Management.