In a recent interview with Democracy Now Barkha Dutt, an award-winning Indian television journalist and author, labeled those citizens in Europe who refuse to vaccine as anti-vaxxers and stated that their decision reflects “a very First World white privilege.” Dutt is certainly right to point to the vaccine apartheid, the fact that COVID-19 related death toll in the non-Western world continues to rise sharply while first world countries have the means and power to secure vaccines for their citizens. However, she misses the point that a large number among those citizens in the First World who refuse the vaccine are non-white and come from migrant and highly underprivileged backgrounds. Her framing of the vaccine apartheid within a racial discourse, reproduces colonial categories that disregard the current demographics and the politics of citizenship in Europe. This outdated view lumps all citizens in Europe not only as white, but also as equally enjoying white privilege, a term that Dutt uses to refer to the high level of state concern to protect its citizens. Here too, she ignores the fact that migrants are mostly excluded from this privilege. Moreover, many migrants, who often come from rather humble educational backgrounds and constitute the lower classes in Western Europe, do not belong to the group traditionally identified with anti-vaxxers. In fact, the term anti-vaxxer reduces the complex and long term structural inequalities that have led members in these communities to refuse vaccination to a simple decision based on health concerns.

Contrary to Dutt’s perspective, I suggest that the success rate of this particular vaccination campaign correlates directly with the level of citizens’ trust in state institutions. Capitalism’s disregard of ethical values, systemic racism, economic marginalization, and culturally insensitive health-care have all contributed to migrants’ lack of trust in state institutions. The high number of migrants resisting the vaccination mirrors the fact that on multiple levels something has gone wrong in our society for decades (if not centuries!), so much so that the vaccine campaign has become a symbol of long term discriminatory state policies in Europe and to refuse it therefore a symbol of resistance to further oppression. The current deadlock is a reminder that trusting state institutions is a privilege that is not shared equally among citizens. Among members of the Iranian community I grew up in in Germany and whom I have spoken with since the beginning of the pandemic, justifications to refuse the vaccine range from statements such as “they have taken our oil now they want to kill us directly” to “they inject a different vaccine for migrants to get rid of us finally,” or “today we are the Jews in Germany, the vaccine is their new method.”

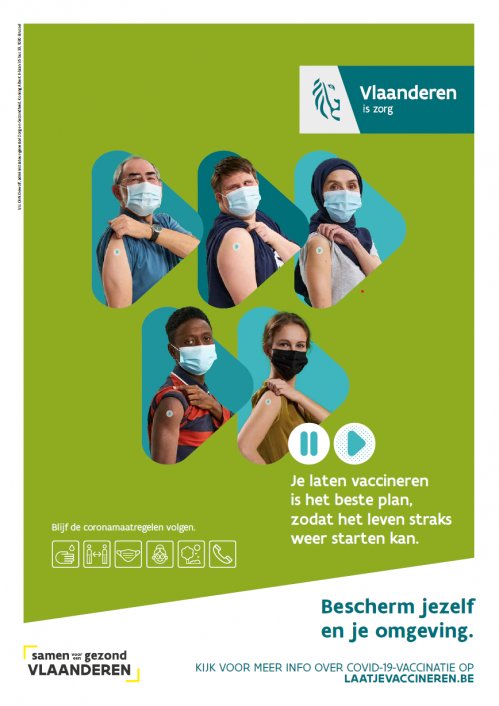

Fighting the pandemic remains only partially successful if it sidelines the cultures of trauma that many migrants live in due to these marginalization practices. European state institutions need to approach the vaccination campaign with more cultural sensitivity and with a recognition that this collective trauma affects and is perceived differently among different strata of the society. For instance, vaccine campaigns that show posters of women with headscarf next to white Europeans and diverse other people, old and young, do not reflect the lived reality of citizenship in Europe, nor do posters of white and black people equally concerned about going through hardship together. These types of posters in fact ask migrants to act as if the state is indeed treating citizens all equally.

Without doubt, the pandemic is a collective trauma, but it has hit hardest the poor and the racial and gender minorities. I would add to the list also those migrants who in addition to bearing the above markers also come from countries where daily life featured authoritarian regimes and political violence. The experience of a sudden change of life, of isolation, of empty streets, of polarization of society, of state changing course constantly, of state interfering in the everyday life of citizens, of rumors mushrooming and adding to anxiety, of high numbers of police presence on the streets, of officials reminding one to wear the mask properly, all of these practices and fears are too familiar for many migrants and have retraumatised segments of the society. Currently, the biggest trigger is the vaccination. The vaccination is literally the most direct contact between their bodies and the state. For many it is a reminder of their daily helplessness vis a vis a violent regime in their home countries and of their marginalization in their adopted country. The vaccine therefore in their eyes is yet another moment of their utter disempowerment and equals to a personal humiliation. With deep-seated mistrust of the state, and faced with discriminatory practices in the host countries, we can perhaps explain the vaccine hesitancy among these migrant communities. While many migrants deny vaccination, the term anti-vaxxer puts the blame on the victims rather than addressing firmly established structural inequalities. The pandemic has finally brought to surface these discriminatory practices. It literally is now a matter of life and death when Western states ignore to focus on pluralism in a meaningful way. To begin with, it is high time that on the EU level policies are implemented that explicitly support a culturally sensitive approach to health care beyond mere slogans and implicit accusations. If states do believe in the power of their own slogans to influence minds, then it is indeed never too late to carry out a heroic act: this time every body counts.

– Roschanack Shaery researches and teaches on the political history of the modern Middle East at the Department of History.