The silver lining of being a digital archive scavenger

In this blogpost I want to reflect on the consequences of working with digital archives for heuristics and source criticism, delineating some possible pitfalls and pointing at unexpected opportunities.

Now that travel restrictions are loosening up and public institutions reopen their gates to the public, I have stumbled upon several posts on my social-media feed of historians who describe their emotions when returning to the archive. The dusty atmosphere and the smell of old books incite overwhelming feelings among those who had to become what I call ‘lockdown-historians’ over the past two years. Academics and amateur historians alike had to refresh their insatiable appetite for the past through the consultation of digital collections and old-fashioned archives.

© Wikimedia Commons

Being part of this professional gluttons, I too have been working from home for more than a year seeking recourse in digital libraries such as Gallica and Retronews for my ongoing doctoral research on the political embedding of consumerism in nineteenth-century France (more on this in Dutch here; in English here). Luckily for me, the efforts of the French government are matched with large-scale initiatives from American universities with the result that French Revolution sources are widely accessible online.

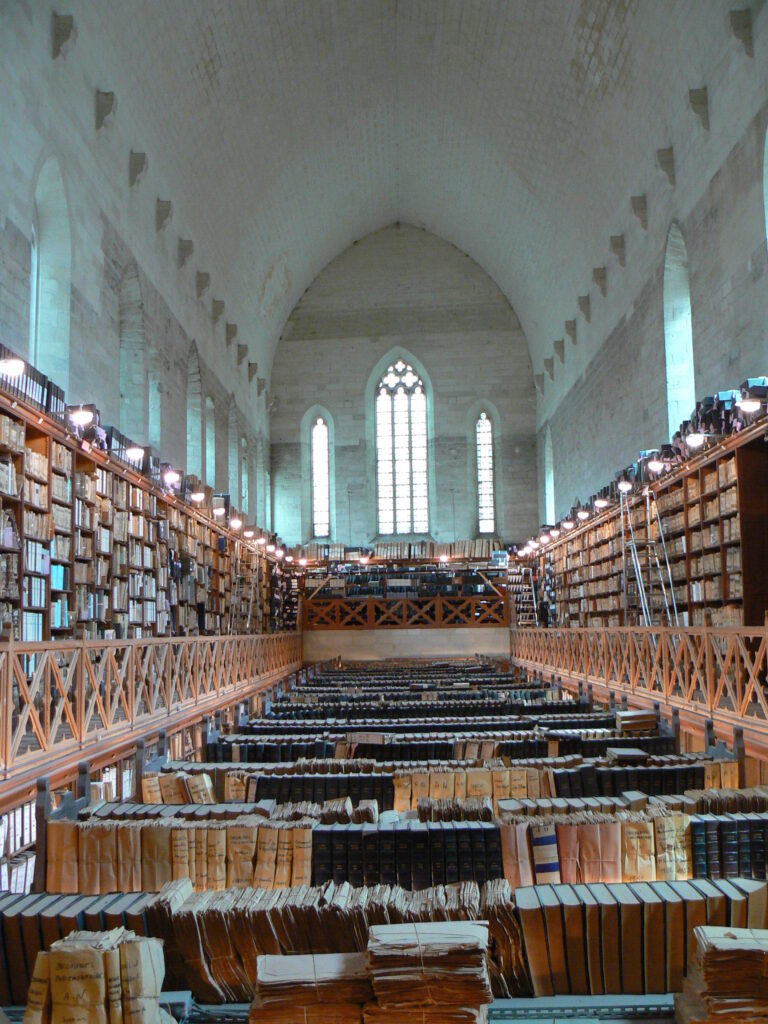

While the conditions that forced us to exclusively consult online archives were unfortunate, I secretly have to admit that it was also a pleasure -for me and especially for everyone who likes things tidy- to stroll through the neat, well-structured and aesthetically attractive interfaces of archival websites. However, these digital utopias could not be further removed from the reality of real-life paper archives, where the meticulous classification and integral description of archival funds tend to be more rare than common. The sleek-looking online source corpora obscure the messy situation on the ground and the chaotic process that the heuristic process often entails. This is certainly true of the source material concerning the French Revolution: when historians interested in this period set foot in the national and departmental archives in France and elsewhere in Europe they see a confusing and intimidating patchwork of uncatalogued archival funds and homonymous publications looming before them, a situation which is despite the great efforts of different generations of archivists common for revolutionary and by extension nineteenth-century source material .

© Wikimedia Commons

In my personal experience, the initial enthusiasm for working with a neatly organized digital corpus of sources was quickly overshadowed when the hard truth of source criticism hit: it turned out that an important part of my sources’ sample, in which I had already invested considerable effort, had been written 6 years after the historical moment that I aimed to investigate, i.e. 1789. Therefore these carefully analysed sources were in the end not at all representative for the period which I intended to research.

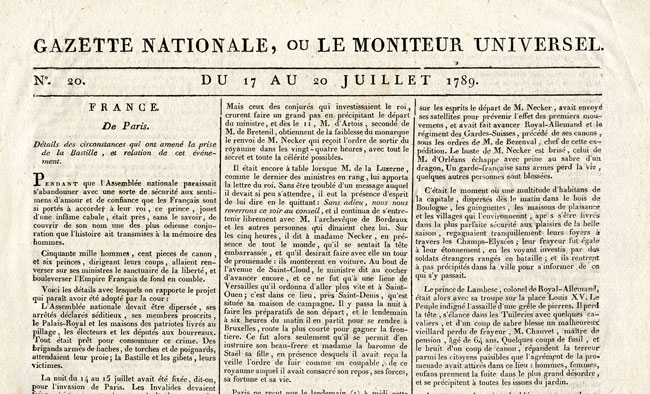

The question that might rise now is of course: how did you not find this out earlier on in the research process? The short answer is: digital archives leave a blind spot in research. The digital archives presented me with a seductively simple and clear image in which the real chronology of the sources had become blurred. The anthology under scrutiny had been published in year IV of the revolutionary calendar (1795-1796) as means to introduce the first issues of the newspaper I am researching and to make this publication called the Moniteur go back further in time to the actual onset of the French Revolution. These issues of the Moniteur were presented on the archival website as written on a later date, though still in the fall of 1789 coinciding with the newspaper’s first-press run.

It was only after consultation of the bibliographical record in the online catalogue that some side remarks pointed to the muddy waters of my sources’ origins. If I would have consulted these newspapers in the paper archives, I would have been obliged to pass by the catalogue to ask for the physical retrieval of the relevant issues from the collection by an archival employee behind the scenes. So writing a counter-factual history of my own research endeavours, I need to acknowledge the fact that working in the real archive would have resulted in being well informed right from the start about the precise whereabouts of my sources. Yet, what I’ve learned from this somewhat episode of getting tricked by the internet as a digital-native millennial is that archival catalogues published online and digital archives’ websites are far from communicating vessels.

This said, not all is lost. Besides the valuable lesson about the not so ever smooth information flow between different archival repertories, this anachronism had a silver lining for me after all. By studying these sources from later in time, I immediately gained a point of reference of what happened later on during the French Revolution in the period known as the Directory. In the end of what I had initially thought of as a set-back- dedicating time to sources that turned out to be anachronistic- allowed me to perform an insightful comparative analysis between two different moments of the French Revolution. Notwithstanding this blessing in disguise, I solemnly hope not to be forced ever again by a global pandemic to test my luck as a digital archive scavenger.

© Wikimedia Commons

Charris De Smet is a historian and PhD Fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders affiliated to the Centre for Political History. She works on a doctoral dissertation studying the political embedding of consumerism in nineteenth-century Paris.