Reportedly four billion people watched the funeral of the British Queen Elizabeth II, making it the most mediatized state ritual to date. Nothing was left to chance: from the tactful seating of countless high guests to the Queen’s favourite pony and corgis paying their last respects. The same held true for the choice of venue. A first service confirmed Westminster Abbey as national hub of royal memory. In this church of her coronation and that of almost all her predecessors, the Queen’s was not the only sovereign corpse. More than two dozen former kings and queens lingered at the back. For the solemn interment, the cortège moved to St George’s Chapel on the grounds of Windsor Castle. There, out of public view, she was afterwards laid to rest in a side chapel next to her husband and relatives, and at close distance of another series of deceased royals.

Both Westminster Abbey and St George’s Chapel owe their prominence to a literally ‘physical’ bond with the crown. Having the status of ‘royal peculiar’ they are exempt from episcopal jurisdiction. Besides institutional privilege, their royal guests brought (and still bring) them influence and wealth.

No such mausoleum existed in the historical Netherlands. Instead there were scattered memorials that reflected the complex and highly fragmented nature of power in these regions. The rulers of the medieval principalities in what are now Belgium and the Netherlands had preferred different churches and monasteries as last resting place. Some of these institutions enjoyed at times the favour of more than one generation, but none obtained a single lasting monopoly on dynastic burial of the like developed in England, France or later Habsburg Spain. When the Netherlands became part of a larger dynastic union, the Burgundians and their Habsburg successors sought relief for their princely souls elsewhere. In these circumstances the tombs and monuments of rulers remained a dispersed and little visible legacy.

However, the shock of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Revolt proved a turning point for dynastic burial. In order to restore its authority the Habsburg government tried to reconnect with the princely past. Among other activities, the archdukes Albert and Isabella (r. 1598-1621), who ruled the reconciled provinces, chose the Brussels collegiate church of St Gudula for their dynastic shrine. They did so by adorning the choir with a monument that remembered all preceding Brabantine dukes (while just one lay in its vault). Although only Albert’s funeral took place in St Gudula, with Isabella mourned in the court chapel, both also designated the former as their final burial spot. If the archdukes hadn’t died childless, it might have been the start of a Netherlandish ‘Westminster Abbey’ or, indeed, an ‘Escorial of the North’. In the words of Ivo Raband: ‘Resembling in this disposition an “El Escorial of the North”, the Brussels High Choir would have changed into a “memorial choir” of the Habsburgs as dukes of Burgundy and – even more so – dukes of Brabant.’

Next to St Gudula several other churches in the Habsburg Netherlands housed dynastic remains and tombs. But the religious violence of previous years and the ravages of time had left their marks. Some monuments threatened to vanish and with it the memory and privileges these represented. For this reason, the archdukes expressed concern for a variety of places that commemorated predecessors and insisted on material restorations.

Most of their attention went to institutions near the Brussels court. Therefore the city’s old Carmelite monastery received in 1607 a generous sum to renovate the fifteenth-century tomb of duchess Joanna of Brabant (†1406). The Brussels Franciscans, watching over Duke John I (†1294), followed in 1620. Here, at the court’s expense, a brand-new memorial plate replaced the original tomb which had been irreparably damaged under Calvinist hands. Archducal funding also extended beyond Brussels or the Brabantine line, as witnessed by a newly erected tomb for Duke John the Blind (†1346) in Luxembourg or (enhanced) memorial masses in princely burial churches elsewhere. One is tempted to see a deliberate plan behind such acts; a thought-out design to recreate continuity after the fractious Revolt. Be that as it may, the concerned institutions cannot be casted as mere passive recipients that underwent a dynastic revival from above.

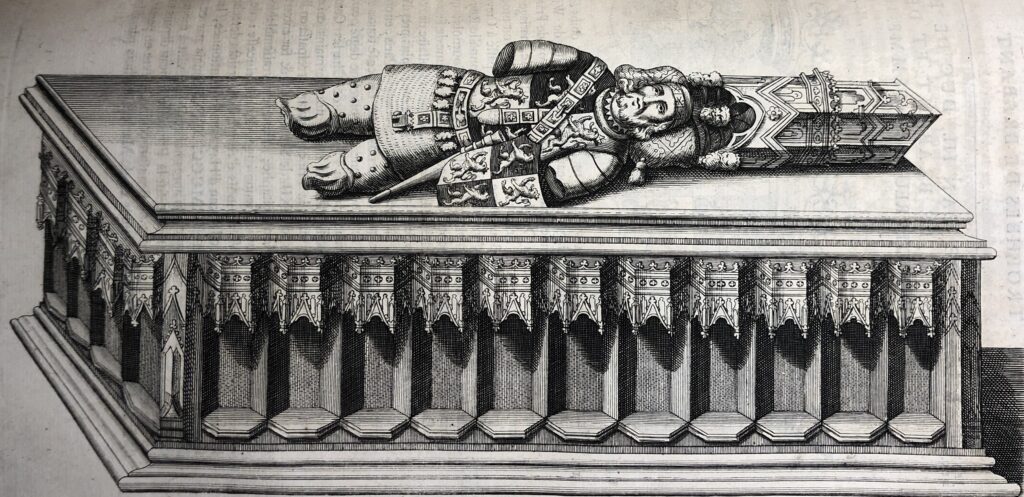

In May 1620 the archducal herald, Adrien de Riebeke, visited the abbey of Villers. Hardly comparable to churches in the heart of power, this place on the outskirts of Brabant possessed princely assets too: the tombs of the dukes Henry II (†1248) and John III (†1355). In dismay, the herald informed his masters about their neglected state. Yet the monks seized the moment with a good excuse. After a history of displacement and a rebellious flirt during the troubles, the community now saw its vacant abbacy filled so that they could resume their dynastic care. As such, the tombs earned them a fresh start.

The example illustrates how even for such institutions in the margin, their political relevance was ensured by the princely dead within their walls — as miniature versions of what their English counterparts still perform today.

Recommended literature:

Steven Thiry, ‘Waking the Dead. The Recovery of Princely Tombs as a Dynastic Obligation in the Habsburg Low Countries’, in: Ethan Matt Kavaler and Birgit Ulrike Münch, eds., Rulers on Display: Tombs and Epitaphs of Princes and the Well-Born in Northern Europe 1470-1670 (Turnhout, forthcoming).

Ivo Raband, Vergängliche Kunst & fortwährende Macht. Die Blijde Inkomst für Erzherzog Ernst von Österreich in Brüssel und Antwerpen, 1594 (Merzhausen, 2019).

Jasper van der Steen, Memory Wars in the Low Countries, 1566-1700 (Leiden, 2015)

Louis Galesloot, ‘Les tombeaux d’Henri II et de Jean III, ducs de Brabant, à l’abbaye de Villers’, Messager des sciences historiques ou archives des arts et de la bibliographie de Belgique (1882), 15-36.

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar kim.overlaet@uantwerpen.be.