The publication of Many Antwerp Hands: Collaborations in Netherlandish Art,[1] which I co-edited with my friend and Rubenianum colleague, Lieneke Nijkamp, provides an opportunity to reflect on whether the subject addressed in this book – which might initially seem to be narrowly directed at an art historical audience of specialists in the art of the early modern Low Countries – might also be of interest to somewhat broader audiences, including political historians.

Collaboration is, on the one hand, a practice that has occurred in all places and time periods, and in a vast array of situations, artistic and otherwise. Yet in the art world – whether museums, auction houses, galleries or academia – individual artists and names still hold sway over the discourse. For historians, while certain historical texts and figures, not to mention historiographic contributions, have held similar sway in various areas of the discipline, there is perhaps no exact analogue. Part of the challenge for art historians in addressing artistic collaboration is that it seems to go against the grain of nineteenth-century notions of authorship and artistic genius that have long shaped the field so insidiously that they remain present, even when we think we are doing our best to put them behind us.

The question of what is political in all of this is a fair one. The role of art as a political medium in the early modern period – from gift giving between rulers to the performative, self-fashioning aspirations of various commissioners of art – gives much art produced in this historical context a decidedly political dimension. In addition, there is, in my view, already a political investment for art historians in deciding to focus on collaboration and collaboratively made works, since that effectively poses a challenge to the overriding individualism that shaped the field at its outset. Focusing on artistic collaboration, then, is necessarily a democratizing gesture, that upsets some of the strictures that tend to govern how we look at, think about, and write about art. The universality of collaboration as a practice, as well as the emphasis in recent years on collaboration – indeed it has become something of a catchword in certain circles – makes it a topic with broad reach and wide-ranging applications beyond art history.

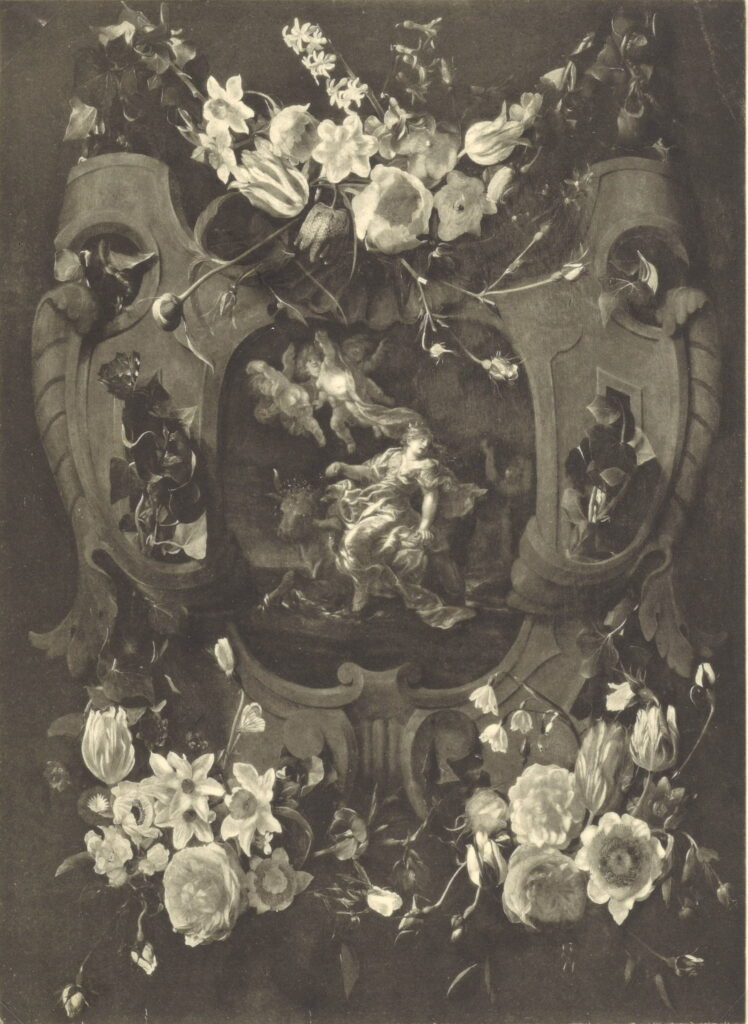

The essays in Many Antwerp Hands apply a range of methodologies, thereby broadening the art historical lens on artistic collaboration and making clearer this subject’s connections with other disciplines. Drawing upon economic and social history, current interests in immigration and mobility, print studies, and technical analysis, the book’s essays embrace a broad spectrum of literary and archival sources along the way. That being said, this book concretely grounds this phenomenon in particular places, moments, and circumstances – especially paintings made collaboratively in the seventeenth-century Southern Netherlands – the better to investigate how it worked, its repercussions, its reception, and its significance. The book thus aims to offer a cohesive narrative and current state-of-the-question on this topic, without entirely isolating this phenomenon. It includes essays that deal with the lead-up to the particular convergence of factors fostering collaboration in seventeenth-century Antwerp (looking especially to Italy but also closer at hand within Flanders in the sixteenth century) and that offer a comparative view of collaboration in the realm of prints, a related yet distinct practice.

Peter Paul Rubens is one of the artists most often associated with politics, not only for his close relationships with and patronage by various rulers (e.g. Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia, King Philip IV, Marie de’ Medici) to produce art sometimes viewed as having had a propagandistic function, but also for his at times (arguably) diplomatic activities.[2] He is also notable for being lionized within art history: in many respects, he is a textbook example of the artist-genius. His art and career are interwoven through many of the essays in this book, but there is just one chapter, written by the late, great Arnout Balis (1952–2021), focused entirely on Rubens’s approach to collaborative artistic production.[3] Arnout – whom we lost in early September, just as this book was published – taught in the history department at the Universiteit Antwerpen, prior to becoming full professor at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel from 2002 to 2013. One of the most respected Rubens experts, Arnout was a brilliant scholar, never afraid to challenge convention, and a rigorous, deeply generous colleague, always ready with an incisive question.

In his essay, rather than focusing on a particular collaborative painting (e.g. the cover image of our book, Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel I, The Sense of Sight, from the series Allegories of the Five Senses, 1617–18, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado) or on one particular, collaboratively executed project (e.g. King Philip IV’s commission of a decorative series from Rubens to decorate the Spanish royal hunting lodge of the Torre de la Parada, for which Rubens enlisted numerous assistants and associates to work with him), Arnout examined more holistically how Rubens thought – visually – and how he involved others at various stages in the process leading from his initial thoughts to his finished projects. Even Rubens, so widely lauded in his own time and ours as a unique genius, understood that collaboration was fundamental to everything he designed and made. Arnout’s essay is an elegant reflection on this aspect of Rubens’s artistic process. It serves as a potent – and political – reminder that no Rubens is simply “by Rubens” and that all cultural objects, come into being as the result of complex processes and relationships.

Abigail D. Newman is a part-time professor of Art History in the History Department at the Universiteit Antwerpen and Research Adviser at the Rubenianum.

[1] Turnhout: Harvey Miller/Brepols, 2021.

[2] For a reassessment of Rubens as a diplomat, see Michael Auwers, “Ambition and Ambivalence: Peter Paul Rubens as a Diplomat,” The Age of Rubens: Diplomacy, Dynastic Politics and the Visual Arts in Early Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Luc Duerloo and R. Malcolm Smuts (Turnhout: Brepols, 2016), 126–41.

[3] Chapter 7, “Many Hands in Rubens’s Workshop: An Exploration.”