M’as-tu-vu. According to the Larousse dictionary, the French phrase can be used as both a noun or adjective wherein an individual’s ostentatiousness, pretentiousness or even vanity is indicated. It is a manner of speaking I often think of when I spend my time scrolling down my Instagram-feed in a mindless search for travel content. And it seems I am not the only one. Ostentatious travel pictures on social media that scream ‘Look where I have been’ or some other variations of m’as-tu-vu are one of the many communicative manifestations of what Austrian journalist and writer Eva Menasse named in her 2023 collection of essays ‘Alles und nichts sagen: Vom Zustand der Debatte in der Digitalmoderne’, Das Eitle Ich or the Vain Ego – a disposition of the inner-self shaped by digital modernity. Still, Instagram and travel pair perfectly as the communicative feature of social media consolidates the inherent performative nature of travel. In the 1980s, social scientists and historians emphasised the important interconnection of travel and performance, with Judith Adler famously stating: “…Performed as an art, travel becomes one means of […] self-fashioning (p. 1368).” Still, our communication about travel and the performative nature of it are as historically contingent as the act of travel itself. Even late medieval and premodern travel reports show signs of similar dynamics. As a medievalist, such statements are always so satisfying to write!

In contrast to modern thought, travel was part of everyday life in the medieval and premodern era as people saw numerous reasons to travel short and long distances, ranging, for instance, from annual fairs or visiting family to pilgrimages, trading affairs and military campaigns. Long-distance travel became increasingly popular and frequent from the fourteenth century onwards. Nicole Chareyron even argued how pilgrimages to Rome, Santiago de Compostella and Jerusalem progressively became a middle-class phenomenon. Other scholars even advocate that medieval Jerusalem-pilgrims can be viewed as ‘proto-tourists’ due to their bargaining of and participation in well-organised Franciscan itineraries and guided tours throughout the Holy Land. Now, communicating or writing about one’s travel became an integral component of the art of travel an sich. The fascinating travel report of the Frenchman Jacques Gassot – in the format of a letter to his uncle – is a case in point.

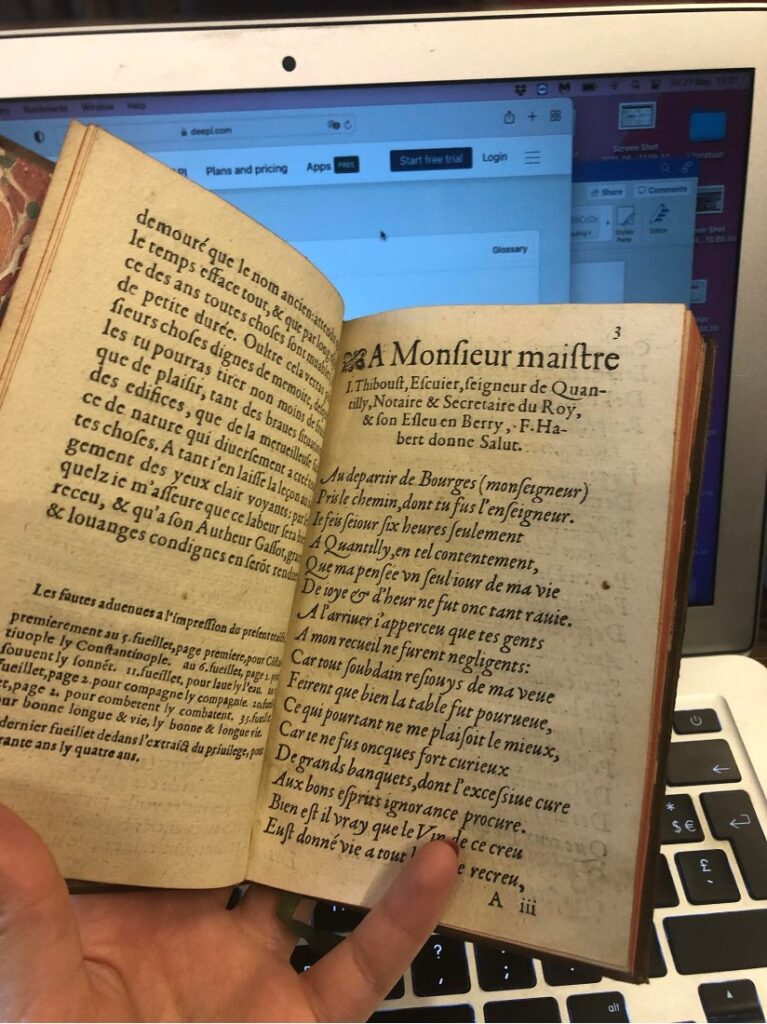

Figure 1 Photo of the Letter of Jacques Gassot to Jacques Thiboust

Born to André Gassot, a royal notary, and Jeanne Rousseau, a member of Bourges’ urban elite, young Gassot enjoyed a fine education and quickly prompted a career at the French court. At the tender age of ca. 23, he went on a diplomatic mission to the Ottoman Empire as a royal secretary and messenger. On December 17th 1547, the young man sailed from Venice to Ragusa, where he disembarked and continued overland to Constantinople. There, he joined the travel party of French ambassador Gabriel de Luetz, seigneur d’Aramon, and partook in the second campaign of the Ottoman-Safavid wars as a consequence of the Franco-Ottoman alliance – a (predominantly) anti-Habsburg, military and commercial alliance between king Francis I and Suleyman the Magnificent. A year after his departure, the aristocrat wrote a letter to his uncle and reported on his travel experiences and discoveries. Young and ambitious, our aristocrat believed travel would be his one-way ticket to ensure his (professional) advancement. Indeed, in his letter he wrote about his travel adventures and the contacts he made during his sojourn: “…that will serve me well for having both some entrance and favour, as for obtaining knowledge and management of affairs, through which I hope to become something (p. 66).” Scholars have differing views on the letter’s printing (and distribution) history. While some argue it was François Habert, a French poet and translator, who had the letter published, others are inclined to believe the publishing-efforts to be his uncle’s doing, Jacques Thiboust – a royal notary, secretary to the king and humanist – in an attempt to boost Gassot’s professional prospects. In any case, the letter was printed in 1550 at the Parisian ‘imprimerie’ of Anthoine le Clerc and its printed form effectively encouraged the wider communicative reach of the letter amongst French literate society.

Here is where remarkably similar mechanisms come into play between the premodern period and modern times on the why and how individuals communicate about travel. It all comes down to the m’as tu vu-dynamic and the related question of ‘how will I be perceived?’ Through carefully curated selfies and snapshots of destinations, the modern travelgrammer presents their self as an intellectual, an adventurer, a foodie or – in my case – a history buff. Ergo, each digital post sends identitarian messages to followers that, in turn, will be interpreted by the followers’ own societal standards. The same can be said for our friend Jacques Gassot. His ambition pushes him to meticulously consider how readers will perceive his behaviour and actions during his travels, which – similarly to modern times – were communicated with use of mass-media. Therefore, the narrations and language in his letter should be interpreted as snapshots aiming to fashion an image of a brave, hard-working and intelligent traveller – a man well-suited for a political career. As a result, he appropriates and performs to the best of his abilities new cultural and behavioural ideals suited for courtiers, influenced by Humanist writings and embodied by King Francis I and his son Henry II, such as elegant affectation, well-versed speech, chivalric bravery and an erudite disposition.

Much like modern foodies tend to post pictures of themselves whilst eating giant pizzas close to the Piazza Navona in Rome, our aristocrat evoked ancient Greek histories when describing his visits to Constantinople. So, Gassot informing his audience that, before Constantinople, the Ottoman city was named ‘Bisantium’ and ‘Roma Nova’, served the means to emulate his interest and knowledge of the antiquities. His erudite demeanour – progressively in vogue amongst premodern French courtiers – was confirmed with interpellations such as: “…I informed myself and studied all singular and notable things that seemed worthy of memory (p. 19).” His critical thinking was assured in his letter as follows: “…I promise you that I have diligently considered and observed their actions, and put into writing what seemed worthy of being noted (p. 29).” His numerous strategic and political descriptions strengthened his potential as a soon-to-be military connoisseur. That is why he, for instance, informed his audience not only on the development but also the cause of the Ottoman-Safavid conflict – adding remarkable chivalric embellishments to the conflict in order to please his aristocratic readers. Description after description – snapshot after snapshot – young Jacques Gassot takes his readers on his travels and laces his narrative with what he knows, observes, and learns. Through this, he constructs his narrative with an (almost obnoxious) m’as-tu-vu undertone to fit his auto-presentation (and professional ambitions).

So, you see, to an extent, posting travel pictures on the gram for all your friends and family to see … it really isn’t all that new. Happy hug a medievalist Day!

Recommended Literature

Jacques Gassot, Le discours du voyage de Venise a Constantinople, contenant la querele du grand Seigneur contre le Sophi: avec elegante description de plusieurs lieux, villes, & citez de la Grece, & choses, admirables en icelle. Par maistre Iacques Gassot, dedié & envoyé a maistre Iaques Tiboust, escuier, Seigneur de Quantilly, Notaire & Secretaire du Roy, & son Esleu en Berry, printed by Antoine le Clerc (Paris), 1550.

M’as-tu-vu, Larousse, https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/m_as-tu-vu/49794#:~:text=%EE%A0%AC%20m%27as%2Dtu%2Dvu,-adjectif%20invariable&text=adjectif%20invariable-,Familier.,%2Dtu%2Dvu%20chez%20eux, consulted on 12th of February 2024.

Judith Adler, ‘Travel as performed art’, American journal of sociology, 1989, 94/6, p. 1368.

Carl Thompson, Travel writing, London : Routledge, 2011, p. 3

Translations

Jacques Gassot, Discours, p. 66 : « …qui me seruira beaucoup, tant pour y avoir quailque entrée & faveur, que pour avoir congoissance & maniement d’affaires, par lesquelles i’espere parvenir a estre quelque chose… »

Jacques Gassot, Discours, p. 19 : « …Ie me suys fort estudié & enquis de toutes choses singulieres, notables & qui me sembloient dignes de mémoire… »

Jacques Gassot, Discours, p. 29: « … ie vous promectz que lay diligement consyderé & observé leurs actions, & redigé par escript ce qui ma semblé digne d’estre noté. »

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar charris.desmet@uantwerpen.be