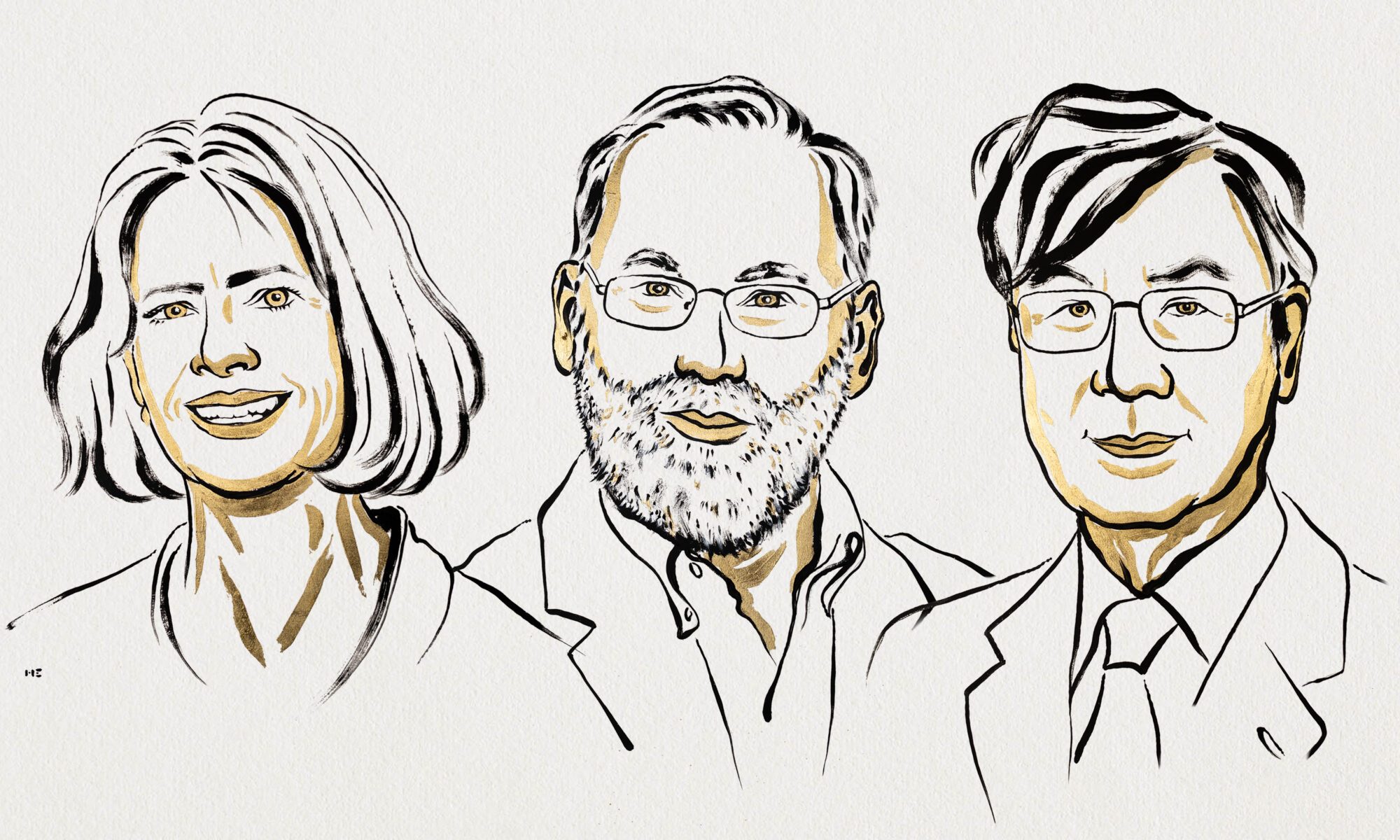

The Nobel Prize in Medicine 2025 is awarded to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Shimon Sakaguchi for their research on how the immune system is kept in check.

The body’s powerful immune system must be regulated, or it may attack our own organs. Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Shimon Sakaguchi are awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine 2025 for their groundbreaking discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance that prevents the immune system from harming the body. ‘The researchers combined different scientific approaches to deepen the understanding of the regulation of the immune system’, says Professor Ingrid De Meester, head of the Laboratory of Medical Biochemistry at the University of Antwerp.

Tregs

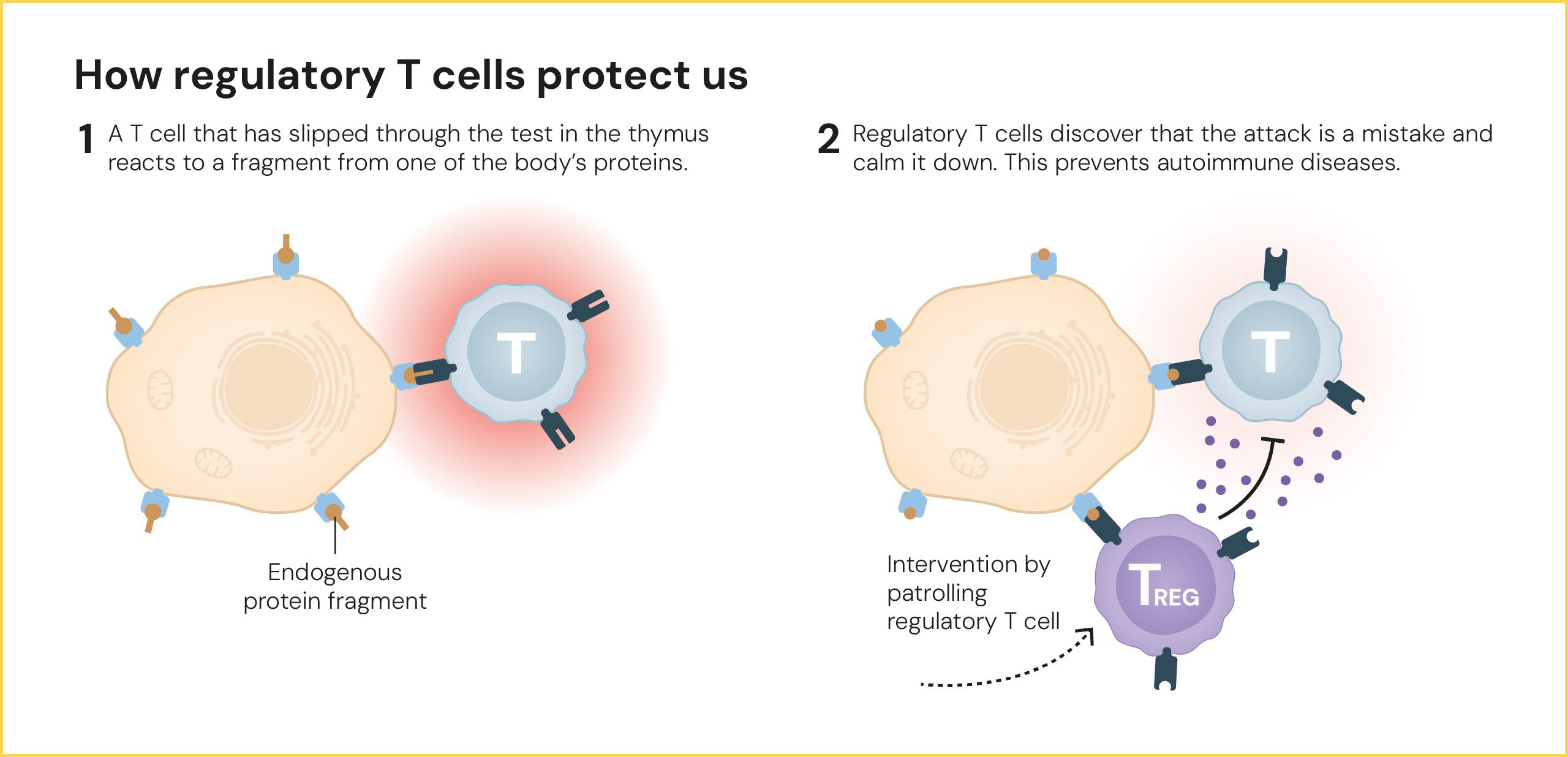

The laureates identified the immune system’s security guards, the regulatory T cells, in short Tregs. These are a type of white blood cells which prevent immune cells from attacking our own body. Already in 1995, Shimon Sakaguchi was able to show that the body’s immune system is much more complex than previously thought. At the time many researchers were convinced that immune tolerance only developed due to potentially harmful immune cells being eliminated in the thymus. This through a process called central tolerance. But Sakaguchi discovered an unknown class of immune cells, the Tregs, which protect the body from autoimmune diseases.

Foxp3

Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell made the other key discovery in 2001, when they presented the explanation for why a specific mouse strain was particularly vulnerable to autoimmune diseases. They had discovered that the mice have a mutation in a gene that they named Foxp3. They also showed that mutations in the human equivalent of this gene cause a serious autoimmune disease, IPEX.

1 + 1 = 3

Two years later, Shimon Sakaguchi was able to link these discoveries. He proved that the Foxp3 gene governs the development of the Tregs. These cells monitor other immune cells and ensure that our immune system tolerates our own tissues.

The discoveries of Sakaguchi, Brunkow and Ramsdell launched the field of peripheral immune tolerance, paving the way for the development of new treatments for cancer and autoimmune diseases. This may also lead to more successful transplantations.

Professor Ingrid De Meester head of the Laboratory of Medical Biochemistry at the University of Antwerp teaches Immunology at the Faculty of Pharmaceutical, Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences. ‘Our students are familiar with the scientific work of the Nobel Prize laureates’, she says. ‘They might remember Chapter 9 on Central and Peripheral Immune Tolerance’, she explains. ‘While Chapters 1 to 8 of the course teach us how our immune system protects us from thousands of different microbes trying to invade our bodies, Chapter 9 explains how the immune system is kept in check.’ ‘The researchers combined different scientific approaches to deepen the understanding of the regulation of the immune system’, says Ingrid De Meester. Including systems biology, an holistic approach in biology that studies living organisms as complex, interconnected systems rather than just as individual parts.

‘The perseverance of Shimon Sakaguchi is inspiring. He faced a lot of skepticism and resistance. I was a young researcher at the time and I can still remember the discussions during international congresses.’

‘The regulation of the immune system is extremely important for its proper functioning, and we still have much to discover about that in vivo “fine-tuning”’, she concludes. Research on the regulation of the immune system has now been awarded a Nobel Prize for the second time in ten years: in 2018, the discovery of ‘immune checkpoint inhibitors’ in cancer immunotherapy also received the prize.