From the viewpoint of a Finnish historian, it was surprising how invisible the centenary of the Antwerp Olympics was in Antwerp when I stayed there at the beginning of this year. In Finland, major newspapers published big stories about the historical Antwerp games already in January 2020, so I expected the approaching centenary to be a huge thing in Belgium and especially in Antwerp. However, I witnessed no sign of preparation for a major commemoration there.

This observation raised a question: why does it look as if the Antwerp Olympics have greater relevance for the national history of Finland than that of Belgium?

The role of mega-events in nation-branding has received considerable scholarly attention in recent years. Scholars have pondered, for instance, why authoritarian regimes (such as Russia) have shown remarkable interest in organizing massive sports and cultural events and how well these events have served the host countries in polishing their image.

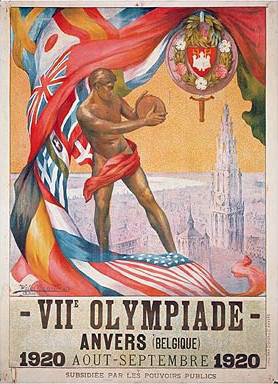

From this perspective, it is also worth looking back further in time, to the early mega-events. The Antwerp Olympics of 1920 are a case in point. This historical event, organized in a specific post-world war context, may reveal a great deal about the significance of big international events not only for nation-branding but for nation-building.

With a primitive knowledge of Belgian history, I have no idea how widely the historical accounts on early twentieth-century Belgium pay attention to the Antwerp Olympics of 1920. Given that scholars, like Maarten Van Ginderachter in 2019, have noted that the nation became the dominant point of identification in Belgium as a result of the First World War, it appears easy to address the role of the Olympics in all this. Sports (and the artistic competitions that were also part of the Olympics in those days) served to reinforce nationalization not only in the host country but also in other participant countries.

In this text, I focus on Finland as a country that had high stakes in Antwerp. The Finnish press followed the Olympic Games of 1920 with keen interest, as the Olympics were the first big international event to which Finland took part as an independent nation-state. Finland had become independent in December 1917 as a result of the First World War and the Russian Revolution, but the country was deeply divided by a bloody civil war that flared up in 1918. In these circumstances, Finnish nationalists viewed sports as one of the key spheres through which national unification could be promoted.

The Antwerp Olympics are known as an event where the current Olympic flag was first introduced. These games were also the first ones to employ the dove as a symbol of peace in the opening ceremony. However, these details were barely mentioned by contemporary Finnish newspapers, which covered the opening ceremony in mid-August 1920. The newspapers were more interested in the opening speech of King Albert I and the arrival of the Finnish team in the Antwerp stadium.

Most importantly, the Finnish press focused on a certain flag incident in the opening ceremony. When the Belgian organizers were supposed to raise a Finnish flag, they erroneously raised a red and yellow flag instead of a blue and white one. The error was soon corrected, but it gave one reporter a reason to regret that Belgians “know so little about our country and about our conditions”. However, the reporter anticipated that Finnish success in the sports events would rapidly improve the situation.

The opening of the Olympics also witnessed another flag scandal. The flag of the Canadian team was torn down in the stadium by a British officer, most likely to demonstrate that Canada was still a dominion of the British Empire. This act drew the attention of the Finnish press, because the Finnish team had confronted similar flag problems in the previous Olympics. In London 1908 and Stockholm 1912, Finns had been qualified to participate independently as a sporting nation, even though Finland had still been part of the Russian Empire.

As the above-mentioned flag incidents reveal, the Antwerp Olympics were a venue for Finnish nation-branding and nation-building par excellence. Finland, as one of the countries that had seceded from empires as a result of the First World War, was now able to attend the Olympics for the first time as an independent state. This was a reason for huge national pride, especially since the Finnish team could now use the national insignia without restrictions, unlike in 1908 and 1912.

The Antwerp Olympics are remembered in Finland also owing to the huge success of Finnish athletes. Finland won 15 gold metals, more than ever since. On the medal table, Finland was fourth, just above Belgium and topped only by the US, Sweden and Great Britain.

The sports competitions that took place in Antwerp featured some of the most legendary Finnish athletes, like the long-distance runners Paavo Nurmi and Hannes Kolehmainen. Nurmi won the first three of his ten Olympic gold medals in Antwerp, whereas the working-class hero Hannes Kolehmainen won the marathon.

In the javelin throw, the Finnish athletes took no less than a quadruple victory, paving the way for a long-time Olympic success of the Finns as javelin throwers. The Finnish wrestlers also excelled in Antwerp with a total of twelve medals.

The host country Belgium distinguished itself especially in archery, with 14 medals, and in football, beating Czechoslovakia in the final. This match was noted also by the contemporary Finnish press because of the disqualification of the Czechoslovakian team. The events leading to the disqualification started when the Czechoslovakian players first protested against both Belgian goals and then left the field before the final whistle. Once again, Finnish newspapers paid attention to flag symbolism as they noted that the furious Belgian audience had torn all the Czechoslovakian flags apart in the stadium after the match.

Besides listing the sports results, some Finnish reporters depicted the city of Antwerp, mentioning the diamond trade, marine traffic and notorious sailor bars. What was less visible in the Finnish reports was the backdrop of the First World War, even if the war’s ravages were a key reason for why the Olympics were awarded to Antwerp. The tensions related to anti-Belgian Flemish nationalism that affected the postwar climate in Flanders, and the annoyance among the Brussels elites about the awarding of the games to Antwerp, were also beyond the scope of Finnish reporters.

When the centenary is at hand in August 2020, the Finnish media continues to highlight Finnish competitors who excelled in Antwerp and underline the national significance of the event. Based on the media coverage, one could claim that the Antwerp games have been historically the second most important Olympics to Finland as a nation. They lose in significance only to the Helsinki Olympics of 1952, another landmark of Finnish nation-building and nation-branding.

To conclude, it indeed seems that the Antwerp Olympics have become a national lieu de mémoire for Finns but less so for Belgians. Nevertheless, from my Finnish perspective, I certainly hope that the city of Antwerp will have a decent share of centennial commemoration this August and September. Hopefully the centennial will also nourish new historical research on the background, events, and impact of the Antwerp games.

– Sami Suodenjoki is a Senior Researcher in the Centre of Excellence in the History of Experiences at Tampere University, Finland. He visited the Centre for Political History at the University of Antwerp in February-March, 2020.