Op donderdag 16 mei gaf prof. Bernard Wasserstein op uitnodiging van het Instituut voor Joodse Geschiedenis, het Centrum voor Stadsgeschiedenis, Power in History en de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte, een lezing getiteld “Israel/Palestine: Two States or One? A Historical Perspective. Na de lezing, die een ruim en gevarieerd publiek trok, ontspon zich een geanimeerde maar respectvolle discussie, die ook nadien werd verdergezet. Vier masterstudenten geschiedenis schreven een kritische tekst over de lezing, die wij graag integraal publiceren. Aangezien we het academische debat willen aanmoedigen, staan we ook open voor andere reflecties op de lezing van professor Wasserstein.

Professor Emeritus Bernard Wasserstein, known for his contributions to modern Jewish history, recently delivered a lecture on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at the University of Antwerp.

The primary focus of his lecture centered on the contentious debate surrounding the one-state versus two-state solution for Israel and Palestine. While advocating for a two-state solution, he did implicitly acknowledge the Palestinian right to statehood. However, his cursory argumentation primarily revolved around its perceived rationality, juxtaposed with the impracticality of a one-state solution. Lacking substantive explanation, the lecture failed to articulate the potential benefits of such a solution for both Israelis and Palestinians, especially amidst persisting violence. While his scholarship is widely respected, this recent presentation, unfortunately, fell short of academic standards, marred by a concerning bias that demands critical scrutiny.

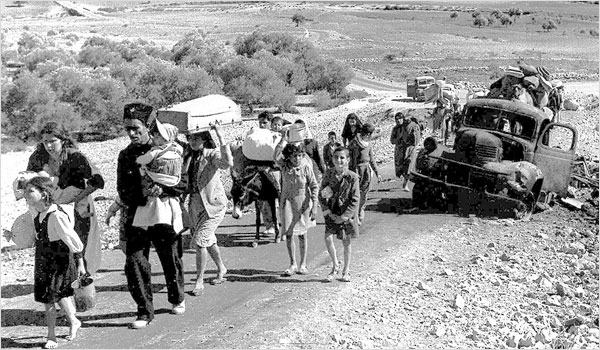

Wasserstein’s denial of the Nakba was evident in his lecture’s timeline of significant events, where this pivotal moment was conspicuously absent. The Nakba of 1948, during which half the Palestinian population was expelled, and which facilitated the creation of Israel, remains a crucial event. However, for Palestinians, it signifies ongoing dispossession, displacement, and the denial of their rights, perpetuating their enduring suffering and struggle for justice in Palestine.[1]Instead of mentioning the Nakba, he repeatedly used phrases like “they were encouraged to move”, a gross understatement that fails to acknowledge the catastrophic nature of the events and the forced displacement experienced by Palestinians. He did eventually address the Nakba briefly following inquiries that prompted it, yet it still does not adequately contextualize the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.

Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes (1947-1948).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Furthermore, Wasserstein consistently referred to the Ottomans as Turks. The Ottomans were a multiethnic empire, and many of their leaders were not ethnically Turks. While the CUP stimulated a Turkification process, that was only in the last decade of their rule and was not as successful in the Arab provinces.[2] His interchangeable characterization of Palestinians as “Arabs” also reflects a reductionist view that erases their distinct national identity. This oversimplification serves to delegitimize Palestinian grievances and perpetuates a skewed narrative that disregards their right to self-determination.[3] Also, his repeated conflation of Jews with Zionists perpetuates a harmful idea that equates Jewish identity with support for Israeli and Zionist policies. This oversimplification ignores the diverse perspectives within the Jewish community and undermines legitimate criticism of Israel’s actions.[4]

Throughout the lecture, Wasserstein also employed euphemistic language such as “Arabs left” and, as mentioned above, “encouraged to move,” effectively sanitizing the forced displacement and dispossession of Palestinians from their homeland. Such euphemisms do not only obscure the reality of Palestinian suffering but also minimize the responsibility of the Israeli state for these injustices. He also alluded to the ‘migration’ of Arabs, drawing a comparison to the ‘migration’ of Zionists, insinuating that the ‘Arabs’ displayed reluctance to integrate into their new nations, and implying a reciprocal unwillingness on the part of host countries, while portraying Zionists as more receptive. This characterization not only misrepresents the historical contexts of these population movements, denying the forced migration and the dynamics of settler colonialism, but also potentially fuels Islamophobic sentiments, particularly at a university located in a city with a significant Muslim migrant population. Moreover, Wasserstein’s assertion that Palestinians failed to integrate into other Arab states overlooks the systemic barriers and discrimination they faced upon the forced displacement. This victim-blaming narrative absolves Israel of its role in perpetuating Palestinian statelessness and ignores the broader geopolitical dynamics that have hindered Palestinian autonomy. He also ascribed the lack of concessions mostly to the Palestinians, disregarding any responsibility of the Israeli authorities. It ignores the power asymmetry inherent in the conflict and disregards Israel’s continued expansion of settlements in the occupied territories. This power imbalance refers to the relative strength of each party, with Israel maintaining a significant military and political advantage over the Palestinians, both influencing negotiations and perpetuating the conflict.[5] Such narratives not only absolve Israel of accountability but also maintain a cycle of violence and injustice.

Wasserstein’s characterization of organizations like the Haganah as “not terrorist” ignores their documented involvement in violence against Palestinian civilians.[6] The Haganah was established in 1920 as an extension of the paramilitary entity Hashomer. Following World War II, operatives from the Haganah and its specialized units, notably the Palmach, initiated a campaign of terrorist activities targeting British military and civilian outposts across Palestine. Their intelligence operations commenced gathering data on Palestinian towns, residences, and individuals, which they subsequently utilized during military campaigns in 1947 and 1948 aimed at displacing Palestinians from their communities. Following the establishment of Israel, the Haganah served as the cornerstone upon which the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) were established, with many of its leaders assuming prominent roles within the IDF hierarchy and occupying key positions within successive Israeli administrations.[7] This assertion stands as a well-established consensus within the historiography, attested by the scholarly contributions of esteemed historians including Professor Saleh Abdel Jawad, Dr. Rona Sela, and Dr. Maher Charif.[8] This whitewashing of history perpetuates a narrative of Israeli exceptionalism and undermines efforts to reckon with past and current atrocities.

Wasserstein also drew a comparison between the Gaza wall and the Berlin Wall, although this completely lacks historical veracity. While the Berlin Wall was erected by occupying forces in Germany, dividing a single nation, the Gaza Wall was constructed by Israel within an apartheid framework, segregating a distinct ethnic group and subjecting them to siege conditions. Ilan Pappé, a renowned Israeli historian, has characterized Gaza as the largest open-air prison, highlighting the severity of the confinement imposed upon its inhabitants. Beyond their shared physicality as barriers, no substantive historical parallel exists between the two structures. Such comparative assertions serve ideological agendas, aiming to obfuscate Israel’s agency in perpetuating apartheid practices.

Additionally, Wasserstein’s omission of the fully annexed Golan Heights and the presence of Israeli settlers there reflects a selective focus on Israeli perspectives while disregarding the Palestinian realities.[9] This biased framing perpetuates a narrative that prioritizes Israeli security concerns over Palestinian rights and aspirations. Thus, in addition to overlooking historical truths, Wasserstein’s narrative suffered from significant omissions. We are aware that it is indeed a challenge to convey exhaustive information in a limited timeframe. However, for the sake of achieving accurate contextualization and mitigating the risk of propagating a biased narrative by omitting important details, it is imperative to ensure a comprehensive portrayal that does justice to the entirety of the narrative and guards against inaccuracies and one-sided perspectives. For instance, Wasserstein failed to acknowledge crucial details such as Herbert Samuel’s Zionist affiliations, which shaped British policy in Palestine.[10] Also, the previously stated absence of any mention of the Nakba or the accountability of the Israeli government in catastrophic events targeting Palestinians further weakened the lecture’s credibility. Similarly, the lack of detailed discussion about the Golan Heights, including its full annexation and the presence of Israeli settlers, underscored a selective approach that favored one narrative while neglecting essential complexities of the conflict. Such oversights not only distort the historical record but also hinder genuine understanding and reconciliation efforts, which was the supposed purpose of this lecture.

In conclusion, Professor Wasserstein’s lecture on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was deeply problematic, characterized by bias, omissions, and historical revisionism. For scholars and educators, it is imperative to critically engage with such presentations and challenge narratives that perpetuate injustice and inequality.

Sumejja Menzil

Noor Ramdani

Hannah Thys

Jo Van Bouwel

[1] Ram Uri, “Ways of Forgetting: Israel and the Obliterated Memory of the Palestinian Nakba”, journal of histrical sociology, 22/3, Oxford, 2009, 366.

Nashef Hanai A. M., “Palestinian culture and the Nakba”, in: Bearing witness, New York: Routledge, 2019.

[2] Ben-Bassat Yuval, “Making Citizens, contesting citizenship in late Ottoman Palestine”, in: Eyal GINIO (red.), Late Ottoman Palestine: The period of Young Turk Rule, Londen: IB Tauris, 2011.

[3] Nassar Issam, “Reflections on Writing the History of Palestinian Identity”, Palestine-Israel journal, 8/4, 2001.

Khalidi Rashid, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, New York: Columbia university press, 1997.

[4] Adam Yehudi, “Zionism and Judaism”, in: Israel and Zion in American Judaism, London: Routledge, 1993.

[5] Gallo Giorgio, “The Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflicts: The Israeli-Palestinian case”, journal of conflict studies, 29, 2009.

[6] Wagner Steven, “Whispers from below: zionist secret diplomacy, terrorism and British security inside and out of Palestine, 1944-47”, journal of imperial and commonwealth history, 42/3, 2014, 440-463.

[7] Charif Maher, “Roots of Zionist Terrorism”, Institute for Palestine Studies, 13, 2023.

[8] Jawad Salah Abdel, “Colonial Anthropology: The Haganah Village Intelligence Archives”, Jerusalem Quarterly, Ramallah, 68, 2017.

Sela Rona, “Scouting Palestinian Territory, 1940-1948: Haganah Village Files, Aerial Photos, and Surveys”, Jerusalem quarterly, 52, 2013.

[9] Ram Moriel, “Colonial conquests and the politics of normalization: The case of the Golan Heights and Northern Cyprus”, Political Geography, 47, 2015, 21-32.

[10] Kedourie Elie, “Sir Herbert Samuel and the government of Palestine”, Middle Eastern Studies, 5/1, 1969, 44-68.

Als je aankondigingen van nieuwe blogteksten in je mailbox wil ontvangen, stuur dan een bericht naar charris.desmet@uantwerpen.be