Witchcraft in DRC artisanal mining sector

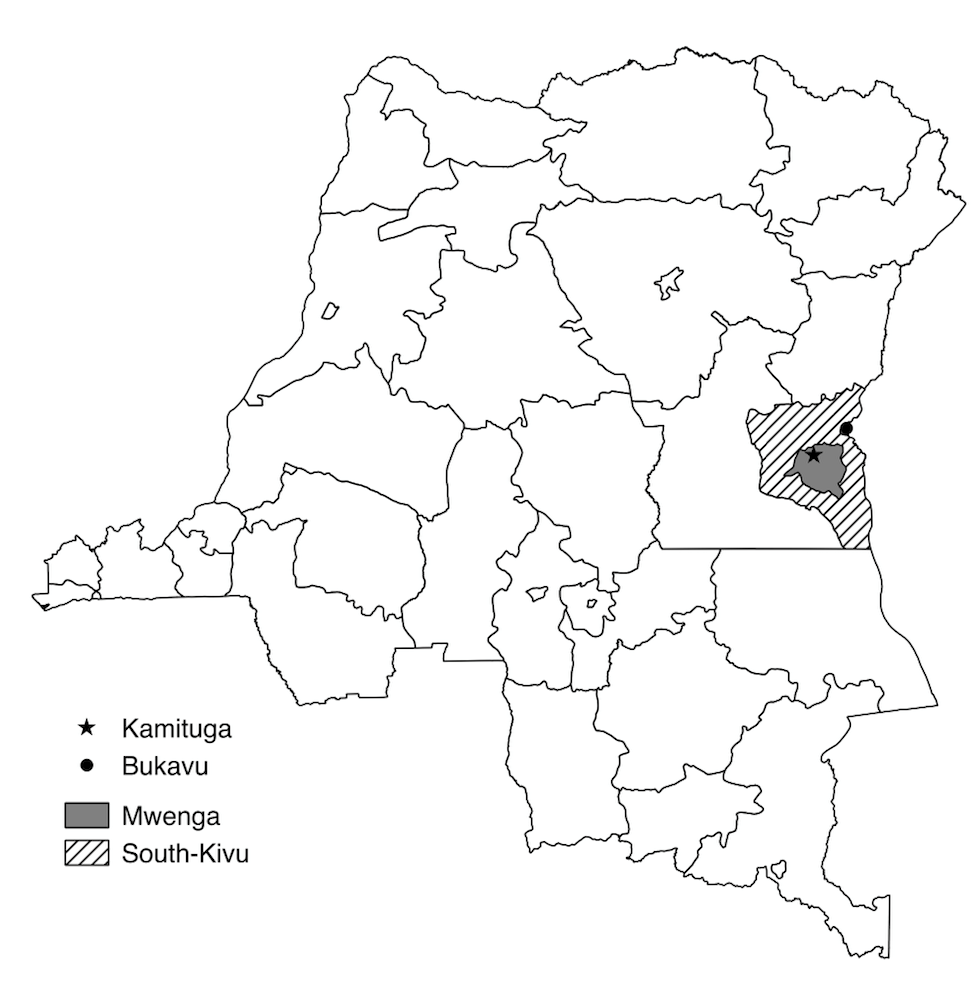

In a recent article, we study witchcraft beliefs and the role they play in the lives of artisanal miners in Kamituga, a town in Eastern DR Congo. Locally, ‘witchcraft’ is called buganga (in Kilega), uganga or uchawi (in Kiswahili), or sorcellerie (in French). Our survey respondents generally understood it as ‘the practice whereby certain persons can launch a curse or spell that can provoke bad events’.

While most existing work on witchcraft takes an ethnographic approach, we conducted a survey among 469 miners, asking both closed and open question.

With this mixed method approach, we set out to understand the ‘rationale’ of witchcraft beliefs. As Peter Leeson puts it: ‘Practices that make people worse off aren’t likely to survive’.

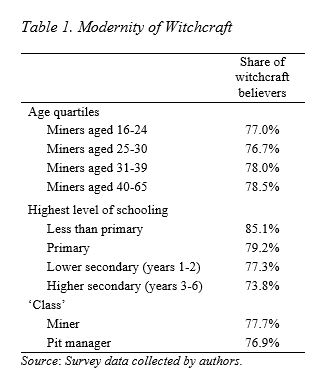

Modernity of witchcraft

Witchcraft beliefs are shared across generations and education levels (see table 1). Among the miners we surveyed in Kamituga, 78% report believing in witchcraft. Witchcraft beliefs are equally high (77%) among the youngest miners in our sample (aged 18 to 24) and not much lower among those with higher secondary schooling (74%).

This fits with the ‘modernity of witchcraft’ thesis: the idea that – instead of making way for a more scientific, positivist, worldview – witchcraft beliefs continue to be of major importance in sub-Saharan Africa, and – in some contexts – even become more vibrant.

We argue that the ‘do-or-die’, ‘zero-sum’ and ‘caught-in-the-middle’ context of artisanal mining in eastern DR Congo provides fertile ground for witchcraft beliefs and accusations.

Do-or-die enterprise

Artisanal mining is a ‘do-or-die’ enterprise. Miners digging for minerals face a high risk of lethal accidents, while those who manage the mining pit take a huge financial gamble – often investing thousands of dollars without a guarantee of finding anything. Witchcraft beliefs help to make sense of the fine line between fortune and misfortune. When financial ruin or other calamities strike, explanations are sought as to why someone is affected, while others are not.

Zero-sum game

Mining is also a ‘zero-sum’ game. A lucky strike by one digging team reduces the potential gain of others. In the setting of artisanal mining, with its frequent occurrences of deadly accidents and disease, the zero-sum situation feeds the collective imaginary that miners sacrifice family members or other miners in order to mobilize evil forces that magically translocate gold in return. As a result, a miner’s lucky strike frequently raises witchcraft suspicions and accusations.

A sector caught in the middle

Finally, the artisanal mining sector is neither fully ‘traditional’, nor completely ‘modern’. The sector is ‘caught in the middle’. Traditional communal relations try to preserve the patrimonial social order, but market forces turn it upside down.

For example, youngsters from modest background can amass great wealth seemingly overnight and outshine the elderly and traditionally prominent people. Witchcraft fears and accusations thrive on this clash between communal and market values. Miners feel haunted by sharing norms and fear spells sent by jealous relatives and neighbours.

- ‘[Witchcraft is on the rise] because of the search for power and means of enrichment, which leads to death in the mining pits’ (miner, age 44).

- ‘Many pit managers use witchcraft and they even make human sacrifices’ (miner, age 35)

- ‘A friend has been cursed by his mother, and he is the only one in our pit not finding gold’ (miner, age 21)

- ‘My family can ‘block’ me if some of them are witches’ (miner, age 40)

- ‘We found gold in our pit, but our neighbours have taken everything by means of witchcraft’ (miner, age 38)

- ‘Witchcraft takes away the luck of some, and gives it to others‘ (miner, age 27)

The super-natural is super-rational

The ‘rationale’ for witchcraft beliefs can also be studied through the lens of the ‘economics of superstition’ – a research line that seeks to demonstrate that the seemingly irrational may be socially useful. In our article we argue that people prefer a society in which risk is shared and assets are not visibly accumulated to a society in which both individual risk and visible inequality are very high. We show that witchcraft beliefs may be welfare improving if the threat of witchcraft accusations helps to enforce a sharing norm and discourages visible wealth accumulation.

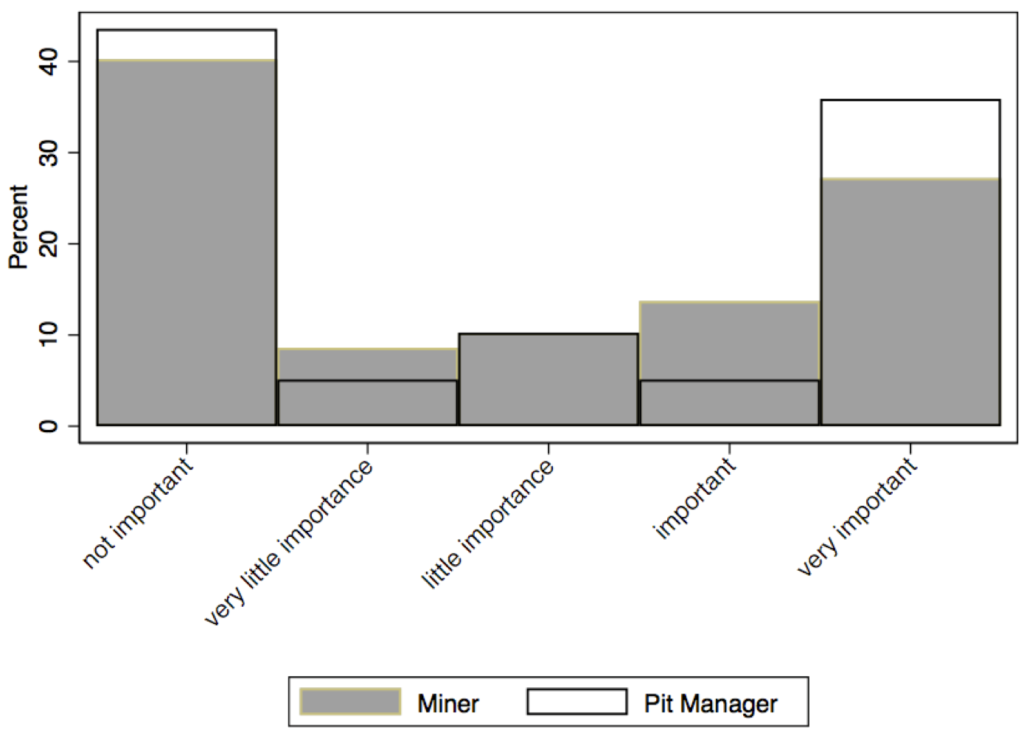

Looking at who is accused of witchcraft, we find that accusations are mainly directed at family members and mining pit managers, both of which belong to a miner’s intimate circle. The accusations amidst family often occur in the context of tensions over income sharing, while those directed at the relatively wealthy pit managers are used by the relatively deprived to seek social and economic justice.

In God we trust

Although 78% of surveyed miners report believing in witchcraft, 41% indicate that witchcraft is ‘not at all’ an important threat to their mining activities. Some of these unfearful believe to have an effective means of protection.

- ‘We pray every day before starting the work, and our pit manager is a pastor’ (miner, age 55)

- ‘If a sorcerer blocks [production], one has to constrain him through prayer because everything comes from God’ (miner, age 31)

Others express a positivist mindset. For instance:

- ‘There is no real proof [of witchcraft]’ (miner, age 34)

- ‘My brother finds gold without taking recourse to witchcraft’ (miner, age 35)

- ‘Those who take recourse to witchcraft don’t find a lot [of gold]’ (miner, age 33), or simply ‘nonsense’ (miner, age 32)

Conclusion

In sum, while our data support the ‘modernity of witchcraft’ thesis, it also reveals that miners are deeply divided on the issue: witchcraft is part of a vivid imagination for some, but not taken seriously by others. And, as expected, the distribution of witchcraft beliefs cannot be captured on a binary scale. A greyscale is more appropriate, with shades of grey that represent both a clash and fusion with the Christian belief system.

Full article

Stoop, N. and Verpoorten, M. (2020), Risk, Envy and Magic in the Artisanal Mining Sector of South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Development and Change. doi:10.1111/dech.12586