About the author

After obtaining her Master’s degree in Development Evaluation and Management at the IOB, Sonya Ochaney interned in Monitoring and Evaluation at a UN organization based in Gaziantep, Turkey. There, the UN provides important assistance to Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) within North East Syria. She is now officially employed and works as the focal point for the Accountability to Affected Populations (AAP) for cross-border activities within the Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL) unit.

Monitoring in Syrian conflict

The Syrian civil conflict, which started almost ten years ago, has necessitated the provision of humanitarian assistance to people displaced internally within the country. An important part of that assistance happens through cross-border operations. This means that the assisting organization itself is not present in the field in Syria, but provides aid to people in need through implementing partners that have field presence within the country.

Likewise, the monitoring and evaluation activities happen remotely. For the purpose of remote management/monitoring of activities and project implementation, there is an extensive reliance on Third Party Monitoring (TPM) actors. These are organizations that work solely in the monitoring and evaluation space and have numerous enumerators/technical persons within the country, who undertake activities as per the demands of the organizations. Our Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL) unit works closely with these TPM. They are provided with all the tools/checklists for the monitoring and are trained in data collection to meet the expectations of the organization.

However, the onset of the CoViD-19 pandemic has severely disrupted the functioning of our organization. Here is how we adapted our remote monitoring to this challenging situation in order to keep our partners safe while continuing to reach our objectives.

Remote monitoring

Monitoring activities range from distribution monitoring, warehouse verification and conducting post-distribution monitoring exercises. These are in-depth interviews conducted with beneficiaries to understand their satisfaction with the assistance received. They provides an opportunity for feedback. The MEAL unit also has a specific focus on Accountability to Affected Populations (AAP), which is especially important in a complex and remote management context of Syria. Accountability to affected populations consists of a holistic approach to involve affected populations in program implementation to ensure their needs are met. Feedback provided from them improves quality of assistance and programming.

We have a designated hotline number, which is advertised through the implementing partners, and through other means such as posters and printing it on the kits distributed to beneficiaries. This hotline number, a community-based complaints mechanism, is an anonymous source for people to lodge their complaints regarding assistance received. This two-way communication mechanism also allows us to reach out to beneficiaries and provide information or request feedback, while also performing an important task of allowing the MEAL team to triangulate data in case any issues are experienced.

Adapting to CoViD-19

The onset of the CoViD-19 pandemic brought about numerous changes in working modalities within the organization. The looming pandemic changed the method of operating for all organizations and implementing partners. The assistance could no longer be provided at one distribution point due to increased exposure; neither could trainings be conducted as before., e.g. the number of participants had to be reduced or trainings had to be conducted virtually wherever possible.

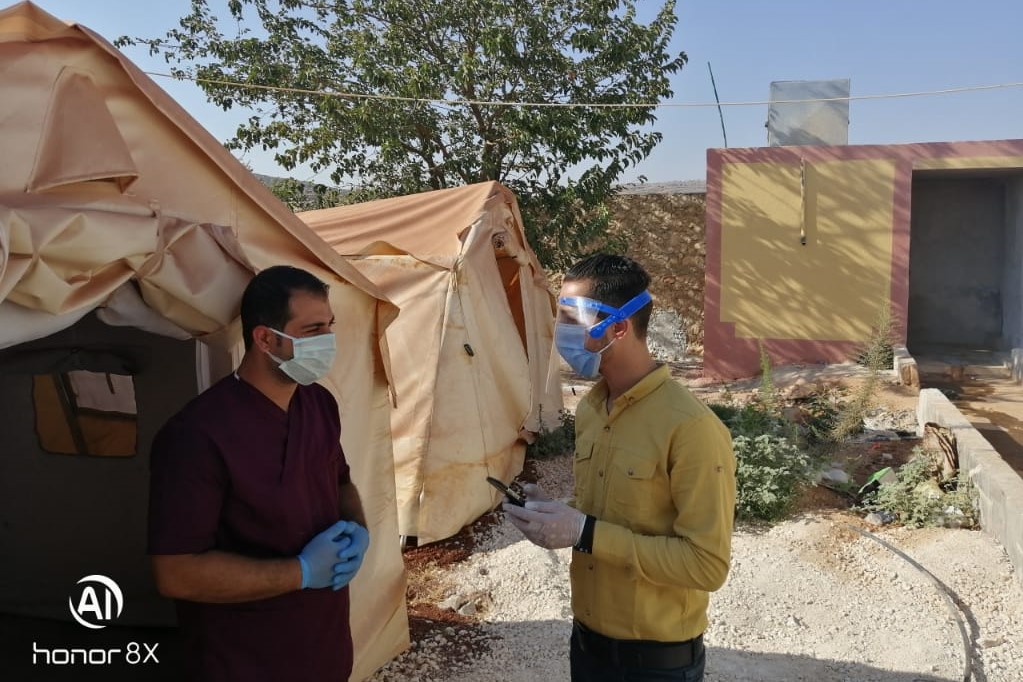

Our remote M&E activities also met with some specific challenges. The guiding concept throughout the adaptation process was the do-no-harm principle for enumerators who are in the field and in close contact with people, and therefore at a greater risk of contracting the virus. Initially, enumerators were provided with basic prevention and safety measures and made aware of symptoms and actions to be taken in case a respondent is displaying symptoms. The MEAL unit also took advantage of the AAP hotline to provide information to beneficiaries who are in a conflict zone and unaware of CoViD-19 and the necessary precautions.

Even with the provision of information, it is incumbent to be cognizant of the fact that these people reside in overcrowded camps that do not offer the space for ‘physical distancing,’ do not have sufficient facilities to maintain hygiene as per requirement, and do not have basic protective gear such as masks. Our organization has increased water provision, ensures the constant sanitizing of public spaces, performed health screenings and provided constant information on prevention measures to beneficiaries in all possible locations.

As cases started to be reported from within Syria, monitoring activities involving close contact with people were suspended for a couple of weeks. Since the monitoring activities have restarted, the enumerators have been advised to refrain from interviewing certain groups such as the elderly and chronically ill, who are disproportionately hit by the pandemic. However, this leads to missing out on vital information from these vulnerable groups. Another major aspect of monitoring in this context is ensuring the most vulnerable are targeted with assistance. Moreover, detecting aid diversion has become more difficult due to the suspension of activities.

In a bid to continue the provision of assistance and monitoring of activities, the organization has provided Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs) to the enumerators and trained them on the measures to be taken when conducting any monitoring activity. These measures include maintaining distance from the respondent, ensuring the respondent is wearing a mask during the interview, following general sanitation rules, suspending the interview in case the respondent is displaying symptoms, and reporting the case to team leaders in the field. This made it possible to restart both humanitarian and monitoring activities. As operations continue, monitoring activities must continue as well, since the humanitarian principles (humanity, neutrality, independence, impartiality) must be abided by, and those in need cannot be left to fend for themselves.

The future of remote monitoring

Although we engage in remote monitoring of our activities, the reliance on human resources is still very high. The nature of the assistance provided plays a role in the resources employed for monitoring. Indeed, organizations that deal with water provision in distant and inaccessible areas have technology at hand to remotely monitor the functioning of these systems and resolve issues with the help of real-time data.

Likewise, certain monitoring activities for emergency humanitarian assistance could increase reliance on technology such as installation of cameras in warehouses and use of drones to monitor distributions. For example, our organization has an innovative ‘Commodity-Tracking System (CTS)’ that allows for assistance items to be tracked from their journey in the warehouse, then to implementing partners’ warehouses in Syria, and right up to the beneficiary. This allows for tracking of aid diversion and ensuring assistance reaches the intended beneficiaries.

However, certain activities that focus on understanding satisfaction with assistance, targeting and beneficiary selection, and awareness of accountability systems continue to rely heavily on in-depth face-to-face interviews. Although other methods exist for data collection, for instance surveys could be conducted telephonically, obvious limitations like a lack of equitable access to technology and other data-related biases remain.

Striking a balance between reliable and valid methods of data collection while ensuring that no individual is at risk is a difficult conversation that has arisen during this pandemic and one that needs to be addressed.

Moment for reflection

These unprecedented challenges have also brought to the fore the importance of the donor community. Organizations working in the field are accountable to their donors, but equally or more so to the humanitarian workers risking their lives and those of the affected populations. This is a time for the donors to extend their support to organizations and be sympathetic to the difficulties of conducting monitoring activities to the fullest and most reliable extent.

I hope that this pandemic allows for a moment of reflection among the humanitarian community, including the donors who, to a large extent, are the more powerful actors. We must endeavor to go back to the drawing board and arrive at better solutions for activity monitoring, while having a continuous dialogue among all actors, including advocacy towards donors.

Ultimately, the humanitarian principle of humanity needs to be extended to those putting themselves in the line of fire to continue offering assistance to those that need it the most.