Social upgrading is about improving working conditions and workers’ rights. It involves measurable standards, such as wages, working hours, and health and safety (Rossi, 2013). Apart from that, it also considers enabling rights, meaning that workers have a voice, can claim their rights, and can collectively organize. How can these rights be achieved?

We take inspiration from LeBaron et al.’s (2018) proposals for improving the rights and welfare of workers in global supply chains: enforcement of labour standards and innovative worker-led models, living wages, increased public goods provisions and basic income, better immigration policies and employers pay principle, better governance, joint employer and intermediary liability, and antidiscrimination measures and positive action. These proposals are covered by the ILO’s Decent Work Agenda which includes employment, standards and rights at work, social protection, and social dialogue (Barrientos, et al., 2011). Despite cases of individual mobility, the constraints to social upgrading for migrant workers are multiple, and structural.

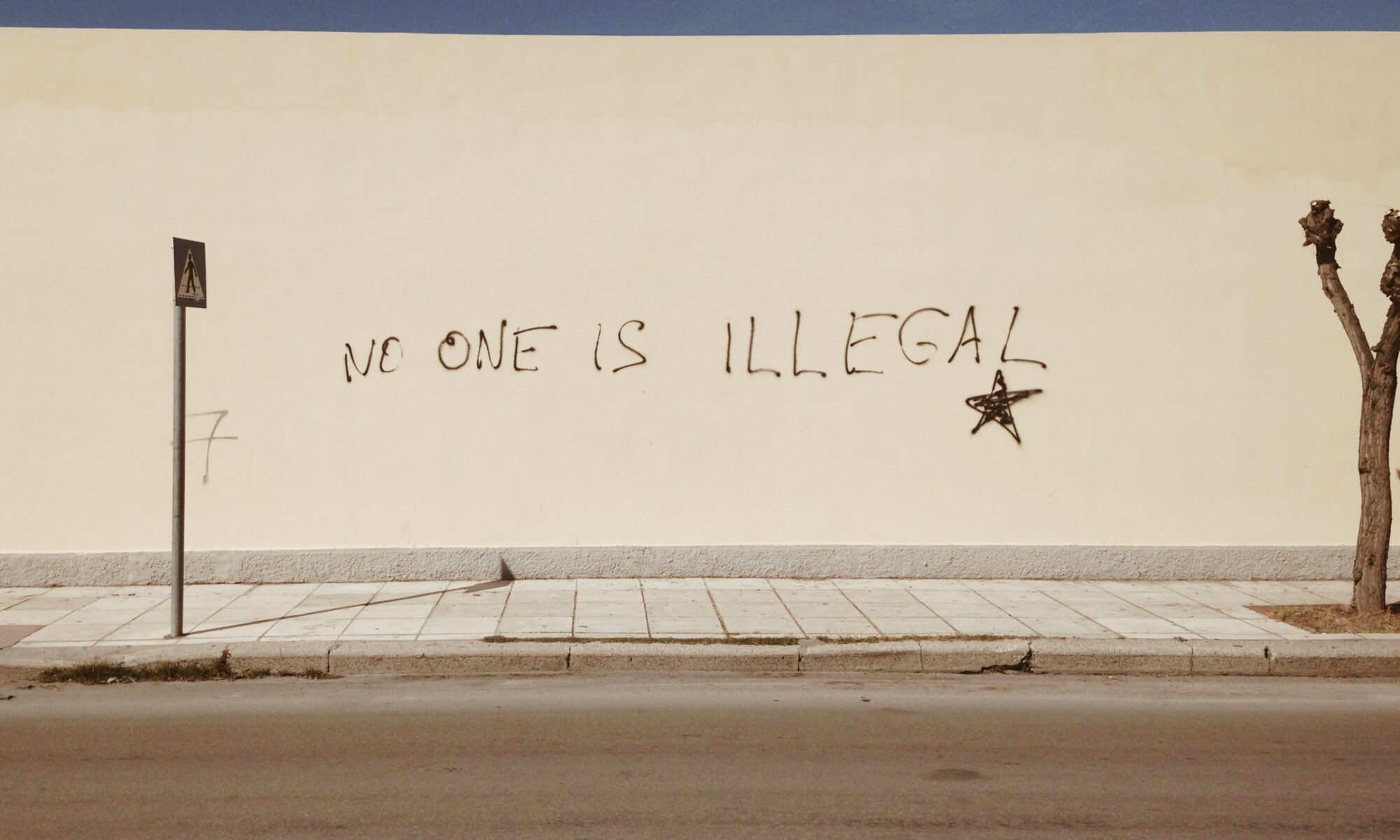

Damaging labels

One major constraint for social upgrading for undocumented migrant workers is how governments, the legal system, and society as a whole see this particular group of people. If the damaging label and accompanying negative connotations of “illegal” perpetuate, then policies might focus on restrictive mobility regimes to prevent the existence of undocumented migrants. This could happen in the form of crackdowns of illegal sourcing agencies in origin countries or deportation from the destination countries.

Such activities could chase undocumented migrants, who have no other viable economic alternative, further underground. This could force them to take riskier routes while migrating or not reporting to authorities when suffering exploitation in fear of being discovered as undocumented and getting deported. This is evident in the advice one interviewee gave to those planning to be a migrant worker: “Never ever fight back against your employer, no matter what happens. Cause they can get you picked up by the police.”

Disenfranchisement

Migrant workers are not represented in the decision-making processes in receiving countries. They are disenfranchised at a political level, especially undocumented migrants. They also lack the social mobilization power to advocate for improvements in working conditions. As suggested by Selwyn (2013), it is the worker’s ability to transform their structural power into associational power that determines the outcomes of social upgrading for workers as a result of the bargaining with capitalist management systems.

In other words, the power of trade and labour unions has largely defined the improvements and institutional arrangements in industrialized countries. However, migrant workers as a group are not organized and they do not have the power to ask for concessions at the economic or political level. Bottom-up collective action may be one avenue towards achieving social upgrading for low-paid migrant workers. Initiatives such as policy advocacy for migrant workers’ rights, integrating migrants in existing trade unions, creating migrants’ own trade unions, forming migrant support and solidarity groups, and other forms of organizations that allow migrant workers, including the undocumented, to share resources are needed.

Some of these are already being carried out. FAIRWORK Belgium for instance helps undocumented migrants exercise their labor rights. It is also interesting to note how migrant groups in other countries are organizing beyond bread-and-butter issues towards migrants’ political empowerment. In Hong Kong, for instance, migrants from the Philippines and Indonesia have formed various organizations, ranging from hobby groups to domestic workers’ unions. These unions often go beyond partnering with NGOs to provide services and training for their members, and lobbying the Hong Kong, Philippines, and Indonesian governments for better working conditions. They also often work together in protesting human rights violations in their home countries, as well as in protests against policies of the IMF/World Bank and agreements of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which they consider as drivers of forced migration (Constable, 2009).

Social security?

Social welfare systems may protect those who are most vulnerable, and thereby give people the ability to say no to forced labour and exploitative working conditions (LeBaron et al., 2018). Belgium’s social security system encompasses old-age and survivor’s pensions, unemployment benefits, insurance for accidents at work, insurance for occupational diseases, family allowances, sickness and disability benefits, and annual vacation limited only for blue-collar employees (Olmen &Wynant, 2020). Yet these are only accessible for documented workers. That’s why several interviewees stressed that having the documents changes everything. One of them summarized it as follows: “Paper is life. If I have my paper, I can do what I want — I can borrow money, buy a house. Anything.”

1 These blog posts are based on essays written by 12 students in the Master in Globalization at IOB, as part of their assignment for the subunit Global Organization of Production. The posts are collectively authored by the 12 students and the lecturer and may reproduce parts of the original essays.

[…] the key ingredients to a successful social upgrading strategy for undocumented migrants were ‘papers’ and ‘learning the language’. Both elements are often mentioned as crucial for the […]