Conflict breaks trust. Genocidal violence obliterates it.

Violent conflict always leads to a wide array of devastation. People are killed, infrastructure is destroyed, and lives are changed forever. It also, however, damages less tangible things such as trust.

Trust is essential in societies. Its presence is a strong predictor of cooperation, functional government and economic growth. Its absence between groups can feed hostilities, potentially leading to vicious cycles of conflict.

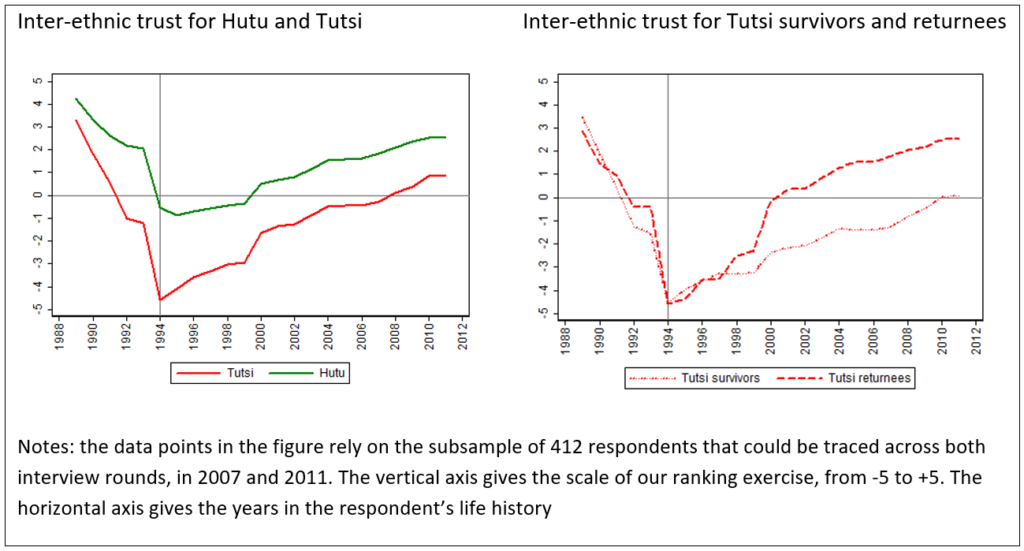

In a recent article, we studied the impact of the 1994 genocide on trust in Rwanda. We analysed more than 400 life history interviews, spanning from before the genocide up to 17 years after it. For each year, the participants, a mix of people that explicitly self-identified as Hutu or Tutsi, indicated their level of inter- and intra-ethnic trust.

Our analysis found that inter-ethnic trust declined when the civil war between the Hutu-led government and Tutsi rebels broke out in 1990. It reached a low point at the time of the 1994 genocide in which the government and ordinary Hutu citizens targeted Tutsis, killing an estimated 600,000 people or 75% of Rwanda’s Tutsi population at the time.

This level of mistrust is, of course, to be expected. Conflict breaks trust, but genocidal violence obliterates it. While most war is aimed at shaping future social interactions, genocide foresees no future social interactions at all. It is aimed at completely removing a group’s ability to survive and reproduce.

In Rwanda, the genocide ended when the, mostly, Tutsi rebels defeated the government. In the following years, trust began to rebuild. 17 years after the genocide, inter-ethnic trust for both Hutu and Tutsi was experienced as positive. This was a remarkably fast recovery given the nature and intimacy of the violence our research participants experienced.

This change, however, was not universal. For Tutsi exiles who returned to Rwanda after the genocide, trust grew steeply. For Tutsis who were already in Rwanda and who directly survived the violence, trust has returned much more slowly and remains incomplete.

This distinction is important. There is a trend in contemporary Rwanda to equate Tutsi identity with survivorship, but many Tutsis did not experience the genocide first hand yet sometimes speak for those that did. It should be remembered that it was those who were physically exposed to the threat of genocidal violence that suffered its worst consequences and bear its heaviest burden to this day.

Double genocide in Rwanda?

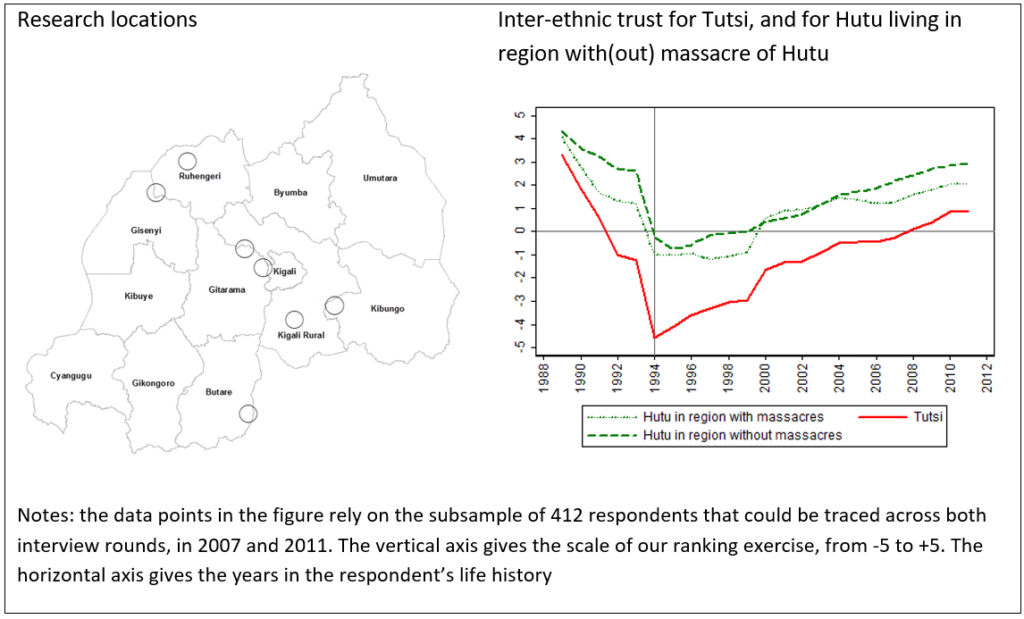

Another finding from our research is that it suggests it is unlikely there was a double genocide in Rwanda. This is the theory – recently revived on flimsy and mostly unverifiable sources – that there in fact were two genocides happening at the time: one against the Tutsi, and one committed by Tutsi fighters and civilians against the Hutu.

Our study finds little evidence of this, at least not on Rwandan soil. If there had been a double genocide, one would expect to see Hutu levels of trust towards Tutsis to reach the same depths as those of Tutsi towards Hutu. But this is not observed in the research in Rwanda.

It is the case that huge numbers of Hutu died. The exact number is extremely difficult to establish, but one method estimates that close to half a million Hutu lives were lost – some in war fighting, reprisal killings or massacres, others through hunger and disease. This occurred for the entire period of the 1990s. Even when focusing on locations where massacres took place, however, we do not observe the total collapse of Hutu trust towards Tutsi as we would expect to see in the event of genocidal violence.

The meaning of death and survivorship

Our research suggests that instead of focusing on the narrative crafted by some of the Tutsi returnees or claims of a double genocide, attention and support should be directed to Tutsi genocide survivors and Hutu communities that were victims of wartime violence and reprisal killings.

As Kizito Mihigo, a Tutsi genocide survivor, sings in “The Meaning of Death”: Though the genocide orphaned me, let it not make me lose empathy for others. Their lives, too, were brutally taken but not qualified as genocide. Those brothers and sisters, they too are human beings. I pray for them. I comfort them. I remember them.

Sadly, these are not the sentiments currently being evoked publicly in contemporary Rwanda. In fact, the contrary may be true. In 2014, Kizito’s song was banned by the Rwandan authorities. On 17 February, 2020, he was found dead in a Rwandan police cell.

This article is republished from the original on African Arguments under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.