Which measures have been taken around the world to contain the spread of CoViD-19? What is the level of popular support for these measures in different countries? How are they enforced? How did different countries make the decisions on which measures to take? We asked our 1158 IOB alumni and our 77 current IOB students. Collectively we researched these topics. Additionally, we asked them about the economic, socio-political and gendered impact of the pandemic and the containment measures. In this blog post we focus on the gendered impact of the pandemic.

The CoViD-19 pandemic may be endangering progress made in gender equality. The data – when gender-disaggregated data is available – points at gender-differentiated effects. Often, these intersect with other layers of inequality, such as age, income, ethnicity, marital status, geographical location, etc. In terms of death rates, men seem to be affected more than women, except in the older age groups, where women are – as expected – overrepresented. In terms of virus exposure, women are at higher risk. They make up 70% of the health work force, and their concentration in frontline and support staff jobs increases their exposure risk. This translates into higher infection rates. In Italy and Spain for example, 66% and 72% of the health workers infected were women (see UN, 2020, p. 11).

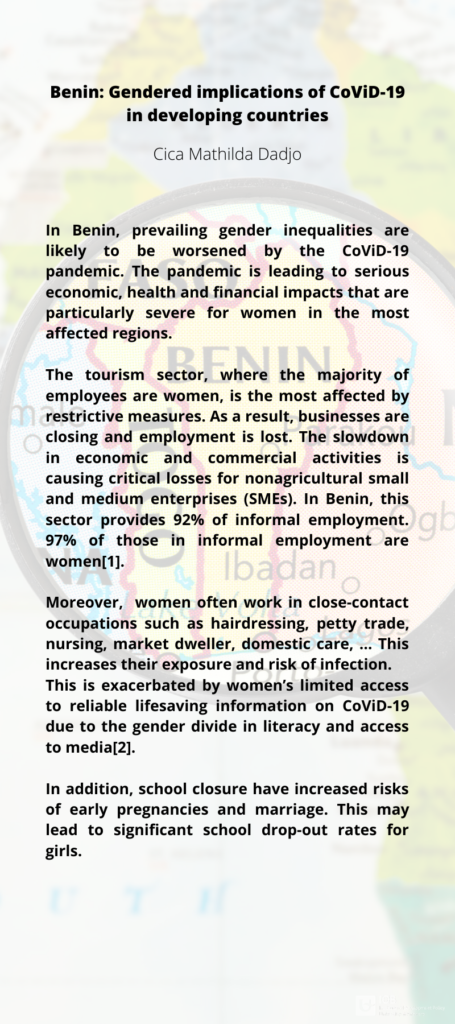

[2] In Benin, 55% of adult women against 36% of men are illiterate and only 51% of adult women own a phone against 79% of men (REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN (2019) Enquête démographique de santé 2018-2019.)

Gender, the economy and domestic violence

The projected negative economic impacts are likely to particularly affect the lower-paid jobs. As globally women’s earnings were 56% of men’s in 2018, this is likely to generate gender-differentiated effects.

Equally important, but far less visible, are the effects on the unpaid economy. In times of lockdown, these effects have been extraordinary. Inside the household, there has been a sharp increase in time spent on childcare in places where schools closed down, adding to an increased health care burden in cases where patients were treated at home. This sharp increase in unpaid household care labour disproportionately falls on women and girls who already spent three times more time in unpaid care and domestic work before the corona crisis than men (UN, 2020, p. 6). Yet, there is also evidence of men taking over some parts of the care labour, which hints at possible changes in gendered patterns of labour allocation. Whether the effects of this unprecedented natural experiment will be sustained, needs further follow-up.

The lockdown and related stress levels has also led to a sharp increase in gender-based and domestic violence, up to 25% where reporting systems exist. This is likely to be an underestimate: the existing underreporting might even be more outspoken in times of confinement and lower access to support (and reporting) services in times of confinement.

Text continues below.

[2] CUT

Global collective research

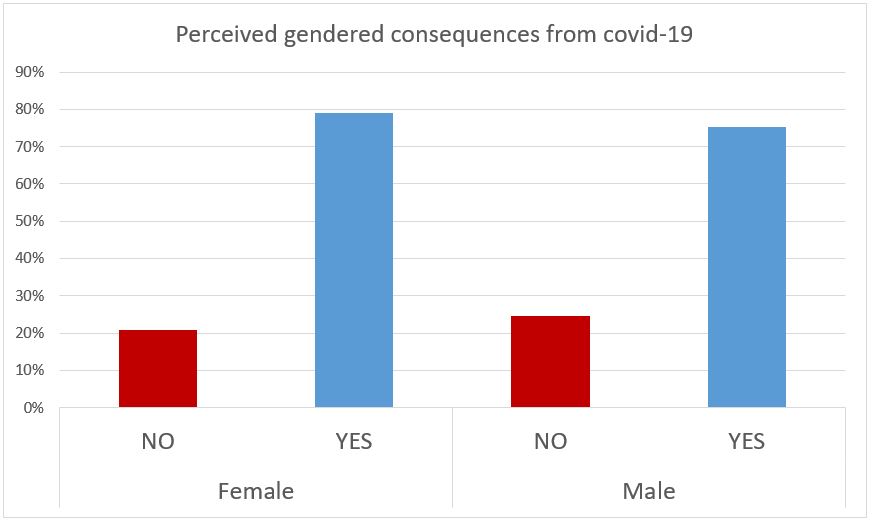

The stocktaking amongst our alumni and students tends to support this evidence. An online survey collected their perceptions about the gendered effects of the CoViD-19 pandemic and the measures implemented to combat the pandemic. 218 alumni and students participated by giving their insights in the matter, 45% of whom women. 77% of our key informants confirm that they perceive gendered impacts of the current CoViD-19 situation. There does not seem to be a clear bias in terms of the gender of the respondent affecting the likelihood of seeing gender consequences: 79% of female respondents identify gender consequences, against 75% among males respondents[1] (Figure 1).

Click image for larger version.

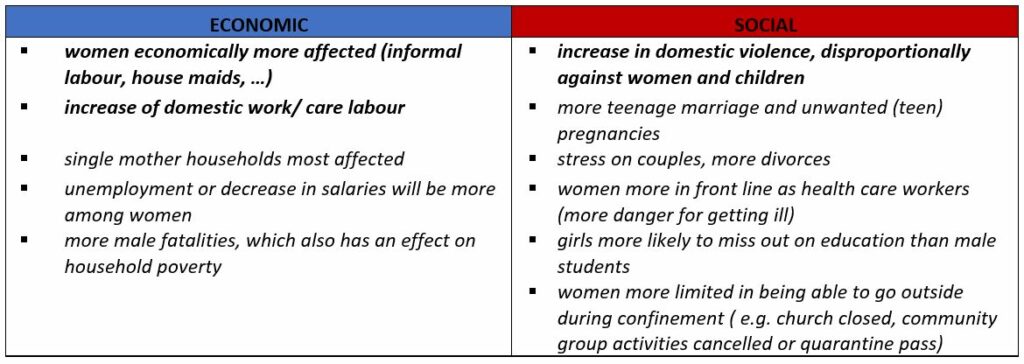

The key respondents highlighted several possible consequences of CoViD-19 that they noticed in their country. The main consequences identified are presented in Table 1. Among these effects, especially the increase in domestic violence (N= 71 times), the economic vulnerability of women (e.g. informal employment, domestic paid housework N= 47) and the increase of unpaid work in the household (N=35) were mentioned most frequently and by respondents around the globe.

Click image for larger version.

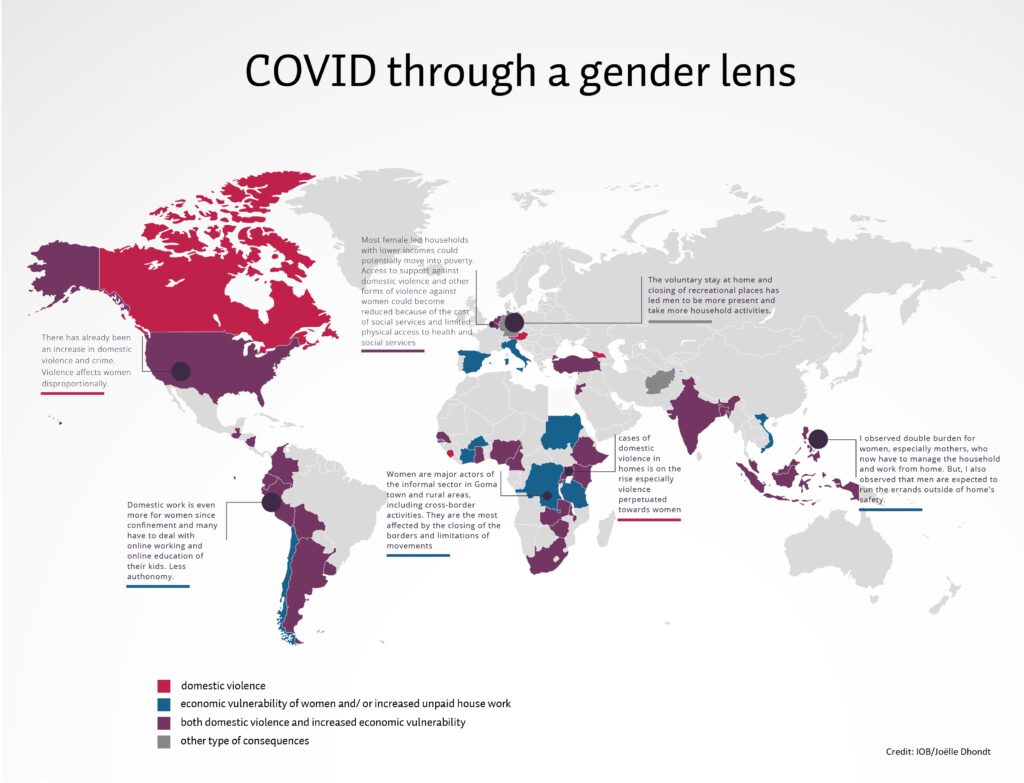

Map 1 clearly illustrates the truly global nature of these gender effects. While the red colour of the country means (only) domestic violence, blue denotes either economic vulnerability of women and/ or increased unpaid house work. Purple means both were mentioned by informants as consequences present in the country. Grey represents other type of consequences mentioned.

Most countries have a combination (= purple) of both social (e.g. domestic violence) and economic (e.g. increased economic vulnerability) gender consequences as a result of the pandemic.

Click image for a larger version.

Gender norms: sticky, but not unchangeable

Gendered effects of a crisis, be it a pandemic, earthquake, tsunami, or an economic crisis are of course not new. They have been documented before, see e.g. Pailey (2016) on the gender impact of the Ebola outbreak and UNAIDS (2012) on the 2008 global economic crisis. Crises do not occur in a social vacuum but in societies where individuals are differently placed. Gender, in addition to and in combination with other layers of inequality (intersectionality), shapes interests, needs, opportunities and challenges. This implies e.g. that labour is not a homogeneous production factor but allocated based on deeply entrenched gender norms in which women are mostly associated with the inside and men with the outside.

Whereas over time women are increasingly participating in paid labour, gender norms are particularly sticky when it comes to unpaid labour. Even in cases where women bring in 100% of the income, they still do the bulk of the care work: 90% in Ghana, 55% in Mexico and 50% in France (World Bank, 2012, p. 220). This double working day is not what you would expect if labour would be perfectly substitutable: the increased opportunity cost of time of female labour would in such cases lead to a higher reallocation of care labour inside the household. Interestingly, whereas gender relations (like most institutions) only tend to evolve very slowly and often as a result of collective action, economic shocks and crisis might lead to abrupt changes in gendered patterns. Whereas the increase in female household care labour during lockdown has been widely documented, there are also cases where men have taken over parts of the household care economy. However, once the situation settles down, gendered patterns tend to be restored. So it remains to be seen how sustained the current changes in gendered allocation of unpaid labour might be.

Text continues below.

Underestimating CoViD-19’s cost

So far, the cost of the crisis has largely been calculated without taking into account the cost in terms of unpaid care labour. This is not surprising and linked to the way in which the GDP is calculated and more specifically the omission of a large part of household care and maintenance activities. Estimates based on time use studies highlight that in this way the GDP is heavily underestimated (by 15,2% in Ecuador and 25,3% in Costa Rica for instance)(UN, 2020, p. 13). The fact that the crisis has led a sharp increase in this unpaid care labour – not captured in statistics – risks heavily underestimating the real costs of the pandemic. And as women tend to disproportionately participate in these activities, also the gendered contribution/costs of the crisis.

Gender and policy measures

Gendered effects do not remain limited to the crisis as such. Policy measures are not genderneutral either. Disregarding gender (as well as other layers of inequality) in policy making might sharpen pre-existing gender inequalities or might even make policy measures ineffective: differently placed individuals tend to respond differently to policy incentives. Research has for example demonstrated how (gender blind) policies that assume the household functions as a unit (neglecting in this way differences in power and preferences amongst household members) leads to policy failures. Reversely, cash transfer schemes, which are worldwide a popular measure to address the current crisis, can be designed in such ways that they trigger changes in intrahousehold allocation processes and outcomes, thus offering opportunities for increased gender equality and empowerment.

Gender-aware policies and budgeting

Gendered effects do not remain limited to the crisis as such. Policy measures are not genderneutral either. Disregarding gender (as well as other layers of inequality) in policy making might sharpen pre-existing gender inequalities or might even make policy measures ineffective: differently placed individuals tend to respond differently to policy incentives. Research has for example demonstrated how (gender blind) policies that assume the household functions as a unit (neglecting in this way differences in power and preferences amongst household members) leads to policy failures. Reversely, cash transfer schemes, which are worldwide a popular measure to address the current crisis, can be designed in such ways that they trigger changes in intrahousehold allocation processes and outcomes, thus offering opportunities for increased gender equality and empowerment.

Gender-aware policies and budgeting

Analysing (ex-ante or ex-post) gender effects of policies can be done through the use of gender responsive budgeting which aims at systematically integrating a gender perspective in policies and budgets to correct for gender bias. A gender-aware policy appraisal for example analyses likely effects of new policies. It takes into account pre- existing inequalities and then suggests changes in policies (or complementary measures) to avoid deepening gender bias and increase gender equality. The ICT sector, which has various gendered challenges and opportunities, might be a particularly interesting sector to start with: various policy domains have heavily relied upon ICT-related devices during the CoViD-19 crisis.

A gender-disaggregated benefit incidence analysis on the other hand can unveil to what extent (differently placed) men and women effectively benefit from government expenditures that are made to attenuate the effects of the CoViD-19 crisis. Along the same lines, revenue incidence analysis helps to study the gendered (and other layers of inequality) impact of differently designed tax systems (e.g. direct versus indirect taxation) that might be put in place to lower budget deficits. Benefit and revenue incidence analysis might go beyond direct income effects but also expand to longer term effects in terms of pensions, social welfare or intrahousehold allocation processes.

Last but not least, the current crisis might not only be an opportunity to make the content of policies and budgets more gender-sensitive, but also to make underlying policy and budgetary processes more inclusive.

Survey

The survey was created by Marijke Verpoorten, Sara Dewachter and Dimitri Renmans.

Student/alumni contributors

Henryson Jusu (Sierra Leone) ,Godfrey Bwanika (Uganda), Naisula Lepariyo (Kenya), Ana Júlia (Brazil) ,Cica Mathilda Dadjo (Benin), Rumbidzai Mpahlo (Zimbabwe), Lien Verbeeck (Belgium), Santiago Silva (Colombia), Samuel S. Omwa (Uganda), Tsegazeab Bezabih (Ethiopia), Salamula Jenipher Biira (Uganda), Dramane Bako (Burkina Faso), Roxane Lemercier (Belgium), Jonathan (Philippines), John Folly Akwetey (Ghana), Naser Qadous (Palestinian Territories), Idrissa Tamba Bindi (Sierra Leone), Manzo Abdourahamane (Niger), Juan Fernando Díaz Lara (Guatemala), Fernando Cando Ortega (Ecuador), Hervé Kouandé (Côte d’Ivoire), Tatevik Davtyan (Armenia), Mayank Sharma (India), Daniela Cristina (Argentina), Abeer Hakouz (Jordan), Bonnie Kiconco K. Mutungi (Uganda),John Melgarejo (Colombia), Maja Vukovic (Montenegro), Geraldine Bythell (Belgium), Camila Contreras (Chile), Huong Vu (Viet Nam), Dennis Penu (Ghana), Silvia González (Ecuador), Natalia Khabalova (Russian Federation), Alemayehu Semunigus (Ethiopia), Boltana Tesfaye Falaha (Ethiopia), Lorena Meza (Peru), Richard Temu (United Republic of Tanzania), Igor Coura de Mendonça (Brazil), Nurina Savitri (Indonesia),Isaac Senyonjo (Uganda), Manzoor E Khoda (Bangladesh), Carlos Allende González (Mexico), Aynul Islam (Bangladesh),Joseph Gana Zanyine (Cameroon), María José Pérez (Guatemala), Habtamu Alemu Jano (Ethiopia), Marcelo Clavijo (Bolivia), Le Le Lan (Viet Nam), Jazzie Alexander (Philippines), Firoz Ahmed (Bangladesh), Gersán Vásquez (Nicaragua), Chilufya Nchito (Zambia), Nancy Ampudia (Ecuador), Rusudan Kardava (Georgia), Thuy (Viet Nam), Cristina Rotaru (Estonia), Shulby Yozar Ariadhy (Indonesia), Zjos Vlaminck (Belgium), Lani Tang (Philippines), Eshetu Demissie (Ethiopia), Kelvin Chirwa (Malawi), Ana Guevara (Bolivia), Adeline Uwonkunda (Rwanda), Nguyen Dinh Tuan (Viet Nam), Ousséni Kinda (Burkina Faso), Abu Said Juel Miah (Bangladesh), Isah Matovu (Uganda), Kondwani Farai Chikadza (Malawi), Annette Kyakuwa Mutoni (Uganda), Pedro Samuel Zapil (Guatemala), Joy Valerie Lopez-Tancioco (Philippines), Abdurahman Hamza (Ethiopia), Yeabsira Tamerat Delelegne (Ethiopia), Maria-Jose Rivera (Ecuador), Dieter Gijsbrechts (Belgium), Dilip Raj Bhatta (Nepal), Kefa Kawanguzi (Uganda), Lovy Rasolofomanana (Madagascar), Maazullah Mamond (Afghanistan), Laura López Muñoz (Colombia), Arsyoni Buana (Indonesia), Nyamadzawo Sibanda (Zimbabwe), Abraham Getachew (Ethiopia), Sharda Khanal (Nepal), Harold Mabwe (United Republic of Tanzania), Arthur Katongole (Uganda), Hauvre Somova (Philippines), Ndille Ndille Kogge (Cameroon), Fatoumatta Saho (Gambia), A H M Belayeth Hussain (Bangladesh), Chrispine Botha (Malawi), Monica Patricia Niño Peña (Colombia), Pierre Merlet (Nicaragua), Cornelius Habeene Muvwema (Zambia), Nahid Sharmin (Bangladesh), Lucia López (Peru), Mikiti M’panda Henry (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Lanny Jauhari (Indonesia), Essa Chanie Mussa (Ethiopia), Michael Gison (Philippines), Grace Dingase Chisamya (Malawi), Eddah Kanini (Kenya), Huong Giang Tran (Viet Nam), Rhoda Nkubah Natukunda (Uganda), Awuor Ponge (Kenya), Joel Siku (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Andrea Mazzini (Ecuador), Veronica Notaro (Italy), Narayan Gyawali (Nepal), Jamie Robertsen (South Africa), Shanjida Shahab Uddin (Bangladesh), Jones Mulenga Bowa (Zambia), Abhinav Alexander Dutt (India), Dejen Minyilu Aragaw (Ethiopia), Sarah Vissers (Netherlands), Nkengfua Alexander (Cameroon), Claudia V. López (Guatemala), Marianelly (Peru), Arnoux Mouafo Nopi (Cameroon), Roy Mutandwa (Zimbabwe), Achem Nkongho Princewill (Cameroon), Zahira Auladin (Mauritius), Ajadi Moheed Adenkunle (Nigeria), Mshinwa Edith Banzi (United Republic of Tanzania), Getachew Dinsa Amente (Ethiopia), Rose P. Villar (Philippines), Tumusiime Collins (Uganda), Al Hassan Cisse (Senegal), Alexandra Maldonado Nuñez (Ecuador), Zalwango Evelyn (Uganda), Kubalasa Dalitso (Malawi), Paul Arias (Ecuador), Zerihun Berhane Weldegebriel (Ethiopia), Mary Chilala (Zambia), Angeline Ndabaningi (Zimbabwe), Ali Agören (Turkey), Trosy (Zimbabwe), Nicholas Mugabi (Uganda), Peter Kirui (Kenya), Wendy Garcia (Nicaragua), Mugisho Chihyoka Laurent (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Gonzalo Antonio Bilbao La Vieja Ruiz (Bolivia), Mapudi Eric Morakiwa (South Africa), Ferdous Farhana Huq (Bangladesh), Yohannes Abraha (Ethiopia), William Pallangyo (United Republic of Tanzania).

[1] One respondent with gender ‘other’ answered to perceive no gendered consequences and so the category had a 100 percent ‘no’ response. However, due to the limited size of the category, it was not represented in Figure 1.