Central America (CA) was already a turbulent region before being hit by the CoViD-19 outbreak. The nations from this small area of the Americas are characterized by endemic violence, political instability, and lack of economic opportunities. As a result, each year 500.000 people travel on average more than 4000 km to try to reach the United States.

The CA-US migration has dropped below average in the last months due to a combination of factors related to the pandemic, such as border closures and lack of jobs in the US. However, historical data shows that migration in the region has a tendency to increase after a drop. This is likely to happen again, since the virus has added yet another complex layer to the push factors that drive people out of their countries: threats of loss of livelihoods, economic recession, and food insecurity.

While recent analyses on CoViD-19 and migration have focused on measuring the economic aftermath of border closures or the condition of migrant workers, less attention has been paid to the possible impacts of the pandemic on the immigration governance and flows, specifically for the CA region. Before elaborating on the short and long term impacts, it is essential to analyze how migration policies have evolved over the last few months.

What has changed so far?

Since the start of the CoViD-19 pandemic, the United States has pushed forward more aggressive anti-migration policies. Human rights advocates fear that CoViD-19 is being used as the perfect excuse to implement hardline policies. In other words, there is a real risk that policies that were originally designed to halt the pandemic could end up being institutionalized.

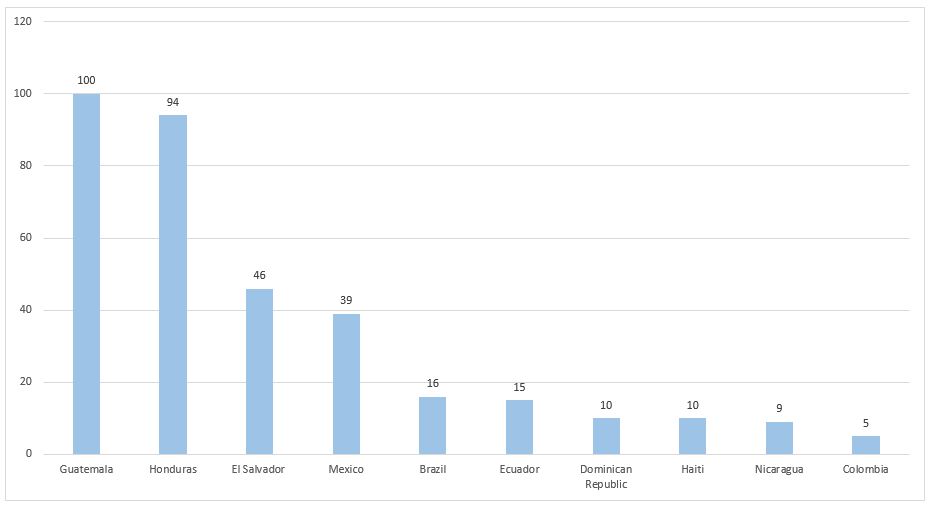

The data seems to back up their claims, at least in the short term: the number of deportations has surged during the pandemic. More than 40.000 people, many of them Central Americans, have been expelled from the US-Mexico border since March. From an estimated 454 deportation flights from the US to Latin America and the Caribbean during the months of February and June, 249 (71%) were heading to Central America, as figure 1 shows below. Many have been deported, even after testing positive for CoViD-19.

This could be explained by the new border regulations that have virtually done away with the asylum system. People apprehended at the southern US border can be deported almost immediately without starting the due immigration process, or having the opportunity to talk to an attorney, since asylum hearings are suspended. This has left many unprotected, including 377 unaccompanied minors who were sent home in a matter of days without legal protection. Before the pandemic, this process could have taken several months.

Restrictions on human mobility because of CoViD-19 have limited access to migration mechanisms. However, the process to harden immigration policies started long before the pandemic. The Migration Protection Protocol (MPP) or “Remain in Mexico Program” (in place since early 2019) is an example of a step taken in this direction.

Under this regulation, asylum seekers are required to wait in Mexico while their cases are under review in the US. The process is confusing and full of red tape. They have been effective at reducing the number of people entering the US: only 0.1% of the requests were granted asylum in 2019.

This has also created a pool of migrants stranded at the borders in a limbo-like scenario. They have neither the option to continue their journey, nor to return home. Thus, migrants have to stay in overcrowded shelters in Mexico, where adhering to CoViD-19 protection measures is next to impossible.

What will be the impacts of these policies?

Before analyzing the possible impacts of the responses to CoViD-19, it is crucial to highlight that the migration governance of Central America and the host countries have been rapidly evolving in recent years. Firstly, Central Americans now make up the largest share of apprehensions at the US southern border, far outnumbering Mexicans. In 2019, Central Americans accounted for 73% of the 851,508 apprehensions.

Secondly, Mexico has shifted from being a migrant-sending to an immigration-receiving country. Mexicans represented 98% of apprehensions at the US border in 2000. That number has decreased to less than 20% in 2019. There are now more Mexicans returning home than irregular Mexican migrants crossing the border.

As a result, it is quite likely that the effects of draconian immigration policies, as well as the aftermath of CoViD-19 itself, will shape the migration flow and governance in the region. Even under a new administration in Washington next year, it is probable that at least some of the policies will be preserved, such as border militarization. Thus, here is a (not comprehensive) list of possible impacts in the short and long term:

In the short term

- Reallocation of foreign assistance: Community-based violence prevention and food security programs have proven to have a positive effect on reducing migration drivers. However, such impacts might take some time to materialize. Therefore, some of the funds for development programs may be cut off. The aid is likely to be reallocated to support Mexico’s immigration security controls and detention centers, to the detriment of initiatives that address the root causes of migration.

- Greater risks for migrants: many people will have the intention to leave as the social-economic aftermath of CoViD-19 worsens. More restrictions at the borders will expose migrants to more perilous routes on their way to the US. The smuggling market usually adjusts the itinerary to continue providing services. This could increase the number of deaths, especially during the summer months, as historic data suggests.

In the long term:

- Geographic reorientation of migration flows: hurdles to head northward could lead to an increase of south-to-south migration. This reorientation of migration flows could represent a significant challenge for middle-income countries, as they will struggle with their economic recovery and weak labor market. It would also represent a substantial income-loss for the families in Central America, since jobs in developing countries are less stable and profitable.

- The proportion of women migrating: in recent years, women migrate as much as men in the region. This trend might change as barriers hinder their options to move abroad. Recent studies suggest that female migrants have a positive economic impact in their home countries: lythey remit their earnings more constant and in a larger fraction than their male counterparts, even when they earn much less.

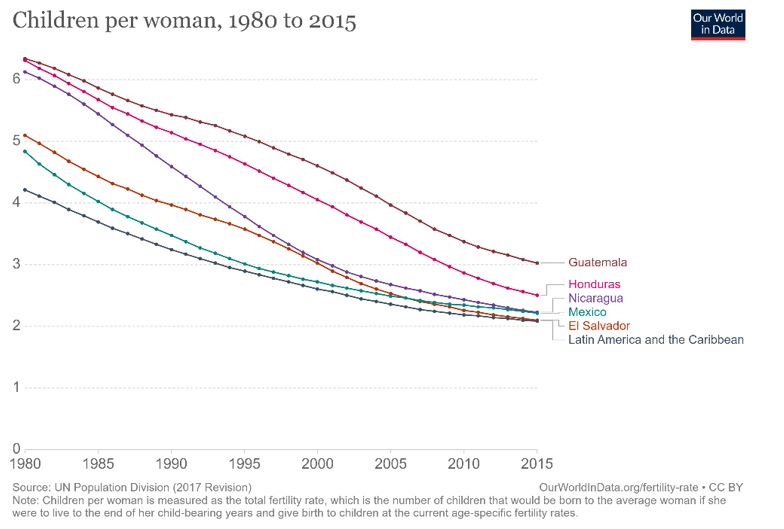

- Deceleration of immigration rates, as it was supposed to happen: while the number of people leaving their countries will increase in the short term, migration to the United States is at a declining rate. This tendency is most likely going to continue in the future, even with a migration rebound. The reason is that Central Americans are having fewer children, and accelerating the demographic transition (see figure 2). Mexico followed a similar pattern and immigration sharply decreased years later. Youth will have more opportunities in the local labor market and will be less likely to risk leaving.

- The long pause: years of restrictive immigration policies targeting both regular and irregular migration could end up creating a long immigration pause for a generation in the US. As the population grows old and fertility rates decrease in America, this would most likely deteriorate the labor market. Realizing the importance of external forces for the economy might take many years.

It is clear that migrant-sending and immigration-receiving countries in the region will face enormous pressure to provide quick solutions to the next migration wave as borders start to re-open. A similar rise of flows in the past has been addressed with restrictive approaches, rather than addressing the underlying causes of migration.

Initial responses are worrisome since policies are progressing towards greater restriction and victimization of migrants. This may lead to long-lasting negative effects on the whole region. Nonetheless, this is also a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to rethink how human mobility can be addressed from a regional and more humane perspective.

Author

Gersán Vásquez Gutiérrez is an economist and holds a master’s in governance and development from the Institute of Development Policy (IOB). He works as a Monitoring and Evaluation practitioner in a child irregular migration prevention project in Nicaragua.