Development cooperation: when politics gets involved (a little too much!)

Whether it be peace and good governance, climate and environmental action, sustainable economic development or human development and many other areas, development cooperation seems to have had no limits in its fields of action for several decades. However, in recent years, budgetary constraints in donor countries have become an issue, often with such aggressiveness (in terms of the impact on the millions of lives that depend on it) and unpredictability (in terms of unanticipated project interruptions).

Development cooperation is no longer only under economic pressure but also, and above all, under political pressure. In two years (2023–2025), the major Western economies have significantly reduced and reconfigured their foreign aid. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), official development assistance (ODA) from the countries of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) fell to USD 212.1 billion in 2024, down 7.1% from 2023. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and various institutes also report additional cuts announced by major donors (the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom and France). This trend directly undermines stable funding for educational, humanitarian and development programmes.

The 2024 Belgian government’s annual report on development cooperation highlights that it is facing significant pressures (humanitarian crises, war in Ukraine, climate shocks, financial volatility) and recommends greater flexibility in budget and efficiency, increased support for fragile countries and resilience, as well as enhanced transparency and independent evaluation. The same report sets out these priorities and illustrates, through operational examples – notably the mandate entrusted to Enabel for reconstruction programmes in Ukraine – the concrete reorientation of certain aid flows. This is supplemented by data published by the OECD, which also confirms a targeted increase in bilateral support to Ukraine in 2024, while reiterating Belgium’s commitment to the least developed countries.

However, these commendable efforts face growing political and ideological obstacles such as budget redeployments, security priorities and pressure from far-right movements that restrict civic space. These constraints undermine the sustainable implementation of development cooperation guidelines and calls into question the very sustainability of partnerships.

It is in this rather gloomy context that this reflection raises the question: How is development cooperation affected by (current) right-wing extremisms? But perhaps the most pertinent question is: is there a future for development cooperation?

Indeed, the rise and normalisation of right-wing, populist or nationalist political currents are reflected in public strategies that go beyond electoral rhetoric, marked by the restriction of civil rights, the questioning of multilateralism and a preference for bilateral or transactional security-based approaches. In addition, there is also an emphasis on national sovereignty, the closing of borders with a discourse of ‘priority for citizens’ that is reflected in laws and administrative practices aimed at controlling NGOs, the press and universities. This is illustrated by recent cases in Hungary denounced by international NGOs and reports on the rule of law in the EU. The following discussion will henceforth explore some pertinent case studies.

Europe and the United States

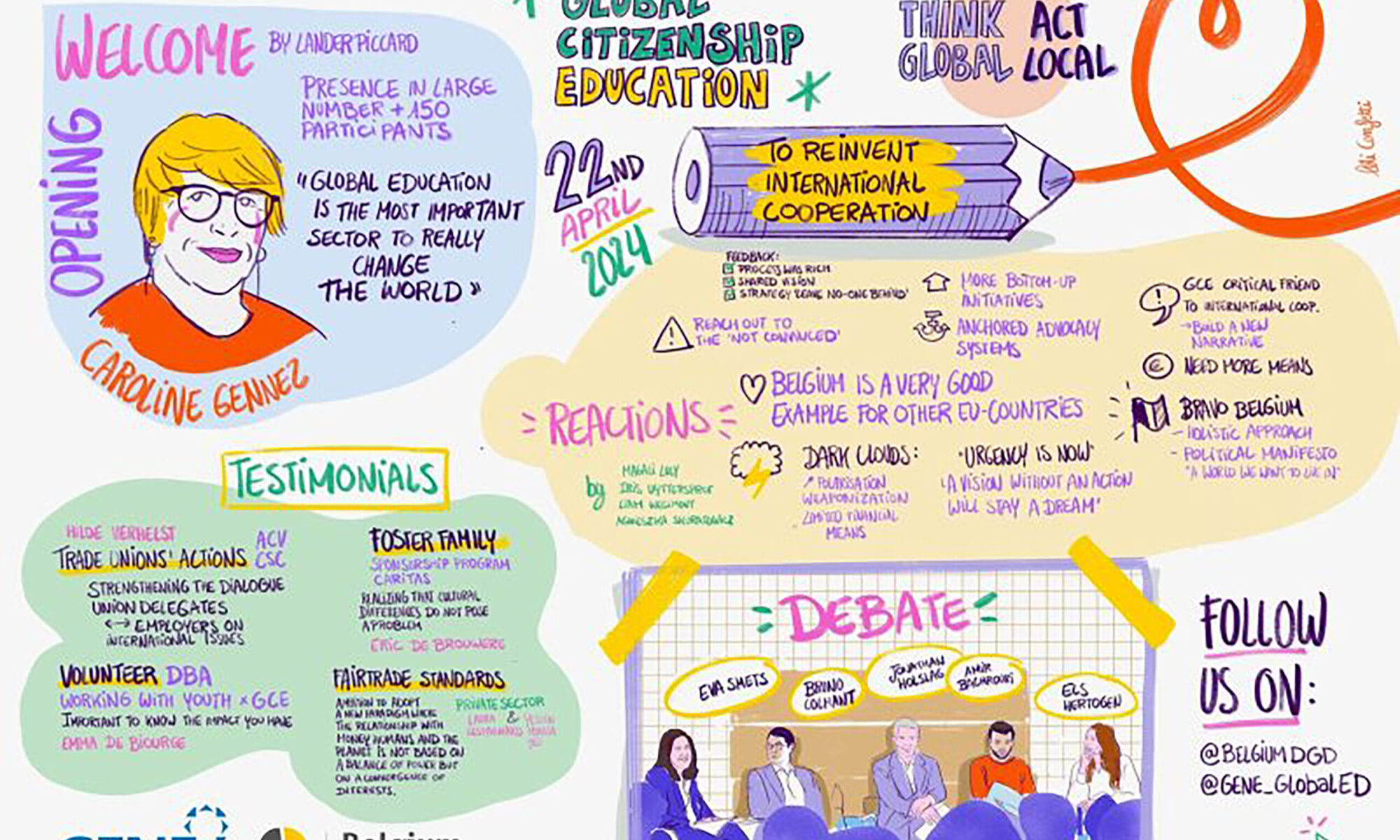

Firstly, in Europe, educational and exchange programmes, despite their robust impact (measurable gains in skills, employability and internationalisation of institutions), are increasingly exposed to the effects of the rise of radical right-wing movements that restrict civic space and security and defence at the expense of development cooperation and international solidarity. In Belgium, this dynamic translates into a direct threat to national scholarship and capacity-building instruments: VLIR-UOS, ARES, bilateral cooperation via Enabel. In the country, the government’s commitment to reduce the cooperation budget by around 25% has been widely reported and is causing concern in the education sector, as it jeopardises the predictability of multi-annual funding and the continuity of scholarships and academic programmes supporting employability and alumni networks. Critically, the budget cut risks weakening precisely those mechanisms that maximise the impact of scholarships. Indeed, without ring-fencing and without long-term guarantees, sustainable training projects and socio-economic benefits for partner countries become vulnerable to political trade-offs and short-term priorities.Next, the 2024 Belgian annual report on development cooperation addresses this issue in a pragmatic manner, reminding us that citizenship education encourages greater international solidarity, as illustrated by the image (left).

This emphasis on citizenship education is in line with the recommendations of international organisations that consider inclusive education and media literacy to be essential tools for preventing violent extremism. Faced with an international situation marked by simultaneous crises and volatile funding, Belgium’s report on development cooperation emphasises the need to ensure the resilience of education systems and to strengthen citizenship skills as a vehicle for social cohesion. In light of the prevailing political and security crises in Africa’s Great Lakes Region, particularly in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the necessity for such an international solidarity is paramount.

Secondly, the United States under the Trump administration is currently exerting major pressure on the international aid architecture by redirecting funding towards domestic and geopolitical priorities, while imposing cuts in humanitarian and development aid, compromising the predictability of support for education, health and food programmes around the world. In the last two years, the US has slashed over $1.4B form the Global Fund, hitting more than 100 countries, weakening the operational capacity of USAID and multilateral agencies. This strategy, which combines an America First stance, security priorities and the use of economic instruments (conditions, sanctions, tariffs), is profoundly reshaping the logic of public cooperation as it had been consolidated since the end of the Cold War. As a result of the programmes being cut, staff are being laid off. This financial crisis is also accompanied by the failing role of the NGO system, which is often criticised in Southern countries. The time has therefore come to adapt to the brutal context of aid cuts, to work independently for civil liberties and systemic change in general.

What conclusions can be drawn?

The threats to development cooperation and the challenges of social justice that have often accompanied it are certainly one more reason to rethink the way North-South collaborations operate. Morally and politically, the instrumentalisation of aid has a cost for democracy and governance autonomy. Indeed, when aid primarily serves national or ideological interests, it erodes confidence in multilateralism, weakens accountability to beneficiary populations and transforms solidarity into an instrument of pressure or geopolitical rivalry. In the short term, this logic may produce political gains for certain governments. On the other side, in the medium to long term, it erodes the trust of local partners, increases the fragility of recipient states and compromises the ability of programmes, particularly educational programmes, to act as bulwarks against extremism.

In an era of crisis in partnerships, cooperation should be seen as a tool for combating the root causes of extremism in all its forms. For that to happen, the future of development cooperation will largely depend on the political and institutional responses provided in countries in the North and in the South. More concretely, it will be necessary to maintain and diversify multilateral funding, provide legal protection for civil society actors and invest in evidence-based educational programmes recognised by UNESCO and specialised networks as effective prevention tools.

Finally, it is therefore necessary to state explicitly that, in the face of the erosion of solidarity mechanisms and the increasing politicisation of aid, only a clear and proactive approach to cooperation (focusing on prevention, education and resilience) can sustainably counter the dynamics that fuel extremism. In other words, if we want to preserve social cohesion and reduce the vulnerabilities exploited by radical discourse, we must reframe development cooperation not as a simple instrument of external interest, but as a public policy for prevention and local capacity building.