United Nations Climate Change Conference 28

From 30 November to 30 December 2023, Dubai welcomed the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference. Two of our alumni closely followed the events in light of their expertise on food systems and the carbon market. Assan Ng’ombe participated in the 2010 IOB Training Programme ‘Governing for Development’ and has worked as a sustainability and resilience expert ever since. Assan shared his excitement that food systems were finally on the table during the climate change agenda for negotiations. Food systems have a been a major contributor to the emissions that contribute to climate change – mainly through land use change – but they also provide a fantastic opportunity to combat climate change and, more importantly, to build the resilience capacities of millions of smallholder farmers in Africa. Assan’s work revolves around making food systems more sustainable. Such systems play an important role in climate adaptation. Faith Temba, on the other hand, has created a career path centered on climate mitigation in carbon markets. Faith graduated from IOB in 2022 and holds an advanced master in Globalisation and Development. Together, we discussed the potential breakthrough in climate adaptation finance and the COP’s failure to establish clear standards for the carbon market.

Climate adaptation

According to Assan, “Food systems can damage our environment, but also potentially help us adapt to changing climatologic conditions. The shortage of extension services in agriculture in Africa is one of the major constraints that limit the capacities of farmers to produce efficiently and sustainably. To increase productivity in order to meet the food requirements of a growing African population (as well as the world population), farmers tend to practice land expansion at the expense of the much needed biodiversity and ecosystems that are crucial for managing local and global climates. Due to their limited adaptation capacities, many farmers are thus caught in a vicious vulnerability cycle of low productivity, climate change and land expansion that further degrades biodiversity. Adaptation technology is essential therefore, as are improved capacities. Food systems should be at the center of the climate agenda as food security needs to be guaranteed if we want to change how people organise their livelihoods around biodiversity resources. There is, therefore, an intricate relationship between people’s need for food, their natural resources and the ecosystem services they provide, and climate change. Assan travelled to COP28 in Dubai with the goal of raising the profile of food systems, and working with African coalitions and groups to make food systems mainstream in the climate agenda. One of COP28’s achievements was ensuring that food systems became recognised as not only a contributor to climate change but also as one of the main solutions, particularly in terms of building adaptation capacities for vulnerable communities.

Generally, finance for climate adaptation is more difficult to secure compared to climate mitigation. Assan attended and closely followed previous COPs in, among others, Madrid, Katowice and Bonn; and believes that it is significant that all parties agreed to finance a “Loss and Damage Fund”. The idea of this fund is not new, but it was the first time that COP participants agreed that impacted countries could receive compensation for the losses and damages caused by climate change. For this to mechanism to be effective, however, there is a need for other climate change interventions which compliment it, such as an effective climate adaptation response system. Adaptation finance, however, remains challenge. Assan explains: “When someone loses their whole house due to a thunderstorm caused by climate change, there is a clear need for compensation. With adaptation, however, it is not as clear-cut as these are a set of – or a combination of – actions and practices that one uses to adjust to a changing environment. These can easily be confused with ordinary development related activities. It is, therefore, much more difficult to quantify and finance these actions. The Loss and Damage Fund might offer compensation, but what it does not do is provide support to rebuild the affected economies in a resilient manner. Currently, the majority of the people in need of adaptation need it to guarantee themselves resilient livelihoods in a constantly changing climate. It is important to note that loss and damage will be an expensive fund because compensation for the loss of or damage to an economy can require a lot of money. It is, therefore, critical that we start thinking of how the loss and damage fund and implementation mechanism can be tied to adaptation measures. The fund should be a mix of technical assistance and actual transfer of funds following events that cause loss and damage. “There is still no comprehensive consensus on how commitments should be structured towards adaptation,” says Assan.

Agenda-setting

This is where African countries should weigh in as a group of nations where most of the support (technical and funding) for adaptation is needed. According to Assan, “Developing countries have what it takes to influence the setting of the agenda in the area of adaptation but need to exercise this influence better by using existing evidence and political action. Developing countries are, indeed, beginning to actively influence agenda-setting in this regard.”

Faith explained that in preparation for COP28, the African Union and Kenya co-hosted the Africa Carbon Conference and invited African Heads of State to formulate a consolidated position before entering carbon negotiations at the COP28.

Despite such preparations and negotiations, “it remains difficult to achieve consensus on key issues that affect developing countries (in Africa). For example, a proposal in support of more climate adaptation finance and technology transfer fell apart when one of the Parties contested an increase in technology transfers and adaptation finance.” Most deals or agreements are brokered outside of the main negotiation room. This is where African country delegations need to build their capacities and improve their ability to bring in their evidence, if they want to influence key decisions in the negotiations.”

Following up on commitments

Even when there is consensus, the real impact of the commitments made will depend on what happens next. Assan clarifies this by saying: “In the case of the damage and loss fund, what remains to be done is develop an implementation and cooperation framework, then specify how it will be managed, and financed.” Past commitments have not always been backed by actual contributions. For instance, the goal of developed countries to jointly mobilise USD 100 billion per year by 2020 in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation was not met in 2021. It is something that we need to work on as a global community. When we state that we are going to raise money, we need to put this money on the table for it to actually make a difference on the ground. From Assan’s point of view: “Accountability concerns play a role, and African countries, along with their counterparts in the developed countries, should be open to showing that they are accountable and transparent and demonstrate that their governance systems are credible in terms of managing climate finance and initiatives. On the other end, countries that provide climate finance have consistently pointed to the lack of, or limited, capacities of countries in the Global South as a reason not to provide funding. To ensure that capacities are built we need to allow the flow of more funding to developing countries. It is important to acknowledge that mistakes will be made and out of this lessons will be learned that will lead to stronger systems to mitigate and manage climate change. A key element in all this is ensuring that there is trust and more collaborative cooperation among countries.”

Ambition

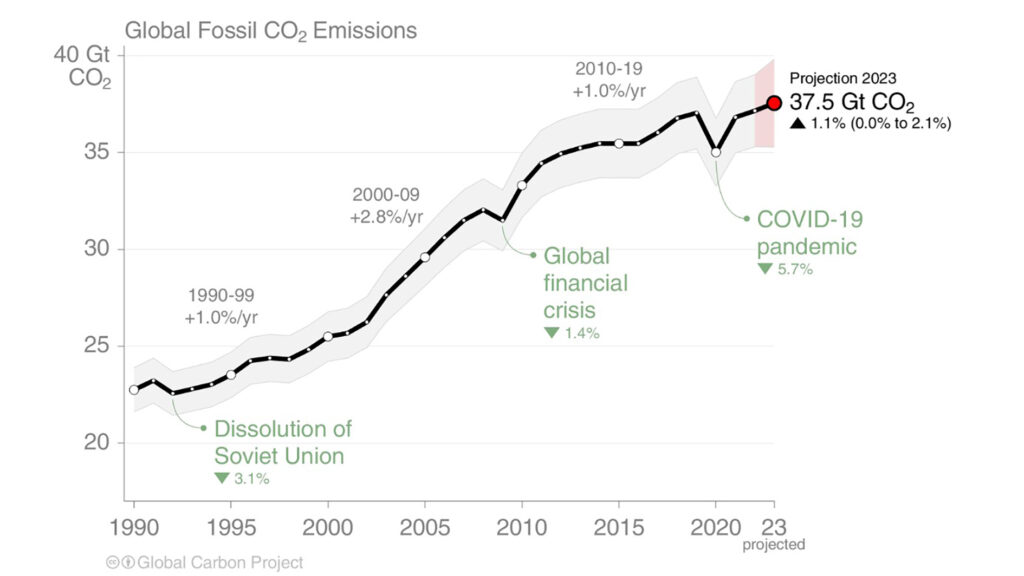

We desperately need more ambition in climate policy. In terms of the financial commitments, the chair of the Least Developed Countries Group commented on the Loss and Damage Fund, saying that, “this outcome is not perfect; we expected more. It reflects the very lowest possible ambition that we could accept rather than what we know, according to the best available science, is necessary to urgently address the climate crisis.” Assan agrees: “When I think of what is needed across the globe, in Africa, Asia, South America and so on, to merely fix the loss and damage will not solve the climate crisis. I would like to see increased commitments towards increasing these funds and ensuring they reach their intended beneficiaries.” There should be willingness to innovate on how funds can trickle down more easily to where the money and technical assistance is needed the most. Carbon markets, for example, provide an important source of climate finance. However, more projects need to be registered and accredited. The time it takes to get carbon projects operational needs to be reduced, due to the urgent nature of climate action. There must be a willingness from multilateral funders to innovate and manage climate finance arrangements with developing countries flexibly.”

Still, COP28 was relatively silent on the carbon market. Faith had hoped for “some type of direction on Article 6.2, and mostly 6.4, of the Paris Agreement as well as more details on the compliance market. The voluntary carbon market has taken off, but the compliance carbon market that potentially increases the ambition to facilitate emissions reductions in sectors covered by regulation and provide mechanisms for international cooperation is still non-existent.” Although Faith recognises the potential of the voluntary carbon market in Kenya and other African countries, she regrets that “the market remains voluntary. Carbon credits help secure access to clean water or clean energy and generate critical funding for sustainability projects in Africa. We should not dismiss this potential, especially when you consider the number of Africans that face energy blackouts. However, to get more traction, more commitment and hence more financing, it is important to have legislation that anchors the objectives. The repeated delays in arriving at an agreement imply delayed action and this obviously impacts the environment. We are headed in the wrong direction and the highest-emitting countries should be the ones setting more ambitious goals. At the same time, reduction targets should take historical responsibilities and the varying capacities of different countries into account. I think that countries that are still growing economically are also within their right to develop.”

The carbon market

The lack of agreement on Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement reinforces imbalances within the carbon market. Initially, this article – tasked with developing standards, guidance, and methodologies for carbon markets and credits – had the most potential. However, yet again, the EU and US could not come to an agreement on article 6.4 at the COP, and discussions were postponed until the next COP. As Faith explains: “LDC’s would benefit from specific rules, as the carbon market is complex and institutional capacity is needed to enter it. Sustainability projects within LDC’s have benefited very little from the carbon market as there is a need for a supportive institutional environment. Clarity on standards, guidance, and methodologies for carbon markets and credits would benefit countries without national frameworks or support.”

Assan points out that “the complexity of the carbon market, together with the lack of specific rules, prevents farmers from receiving the correct compensation for the carbon stored at their farms. Food systems play a role in climate mitigation through agroforestry and regenerative agriculture and farmers can potentially access carbon credits. Yet, the market is dominated by developed countries that buy up the carbon at sub-optimal prices. There definitely is a need for more transparency and accountability, backed by strong regulatory frameworks, in the area of carbon markets. Often farmers do not know who is buying and know little about the processes involved in the trading of carbon credits that they manage on their farms. There are opportunistic brokers that facilitate the signing of agreements for farmers and communities to preserve trees on their farms and land in exchange for some compensation. The complexity of the systems prevents most local communities/smallholder farmers from knowing if they are being paid fair prices. Clear rules around price-setting are needed. I think that we should all be working towards a system and frameworks that promote accountability, ease of tracking/traceability, and transparency within the carbon space, using the COP mechanisms. After all, ultimately it is a global good. Everybody needs that carbon to be sequestered somewhere.”

Growing ambition?

African countries need to have a stronger presence on the agenda of each upcoming COP. Climate adaptation funding and the role of food systems in adaptation must be given greater prominence on the climate agenda. Concretely, while capacity is built, and consolidated positions are formulated before entering debates, it still remains challenging to weigh in when decisions are made outside of the main negotiation room. Some topics also remained unresolved, such as the details of Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement and regarding the carbon market in general. LDC’s and small-scale farmers would benefit from more regulation. Hopefully, this gap will soon be addressed, because global regulation could compensate for institutional lacunae in LDC’s and promote transparency, helping small-scale farmers get fair compensations for carbon sequestration.

To conclude, we concur with Assan and believe that mitigation and adaptation should go hand in hand. For those whose work focuses on farmland, particularly that of smallholder producers, there is a risk that these communities may be restricted when cultivating their lands for food because of unclear carbon sequestration trading schemes. Therefore, Assan emphasises the need to integrate sustainable practices into carbon trading systems to ensure continuation of farming livelihoods and increased complementarity of carbon trading systems in these farming communities.