In December 2020, the United Nations General Assemblee adopted a resolution on the “Promotion of inclusive and effective tax cooperation”, an essential step to “Rescue the SDGs”[1]. The Africa Group at the UN, under Nigerian leadership, spearheaded the draft resolution in November and managed to rally up approval despite resistance from the OECD and the United States[2]. Whilst this call for UN over OECD tax leadership is not new, it is exceptional that this resolution got approved. Countries worldwide count on coordination and reform to tax multinational enterprises and close down loopholes at the basis of recurrent tax avoidance scandals. After the global financial crisis in 2007, the G20 mandated the OECD – the most powerful governing body in international taxation – to redraw the global design. And it did so, with extensive working groups, a multilateral instrument to amend existing bilateral tax treaties, and pillars 1 and 2, while experimenting in more inclusive governance-making. But, even though the dust of these reforms has not settled, voices mumble that these reforms are not inclusive, equitable, nor comprehensive enough, and finally African countries said “enough” during last December’s General Assemblee meeting. Is this a sign that African countries are done being norm-takers in international taxation? And does this resolution set the stage for more just global tax rules? We asked these questions to Professor Tarcísio Diniz Magalhães, an expert in international taxation at the University of Antwerp, and Richard Kweitsu, an IOB alumnus, previously employed by the Ghana revenue authority and currently writing a PhD at the University of Florida.

Looking back: Why has it been enough

International taxation has never been a level playing field. Developing countries entered the policy game when most of the rules were set – not surprisingly in favor of capital exporting countries –, and when reform became inevitable, the OECD stepped in to move beyond distributional conflicts at the UN. Tax touches upon the essence of sovereignty – a state’s right to tax -, and states are reluctant to restrict their freedom to tax through international agreements. Nonetheless, the OECD is a powerful norm-setting body worldwide and its soft law instruments shape the global regime. The OECD model double tax treaty serves as the basis of most bilateral tax treaties, and the OECD transfer pricing guidelines form the global benchmark to split international profits over tax jurisdictions. Yet, the rules, along with their bias towards capital exporting countries, as well as the position of the OECD itself, politicized over the last decade.

Legitimacy constraints

Prof. Magalhães explains that: “in international tax is, and especially in international business taxation, that one institution, the OECD prevails over others worldwide. Yet, membership to the OECD is limited compared to the UN which includes almost all the countries in the world. The OECD claims to be the authority in terms of tax policies because of the expertise that is behind the organization, and this discourse seemed to convince almost everyone”. He further criticizes the hypocrisy of the OECD where it on the one hand remains a club of countries that only allows countries in when living up to its expectations, but on the other hand, because it needs – wants – to be the global tax center, it invites other countries to participate and creates things such as the ‘Inclusive Framework’.

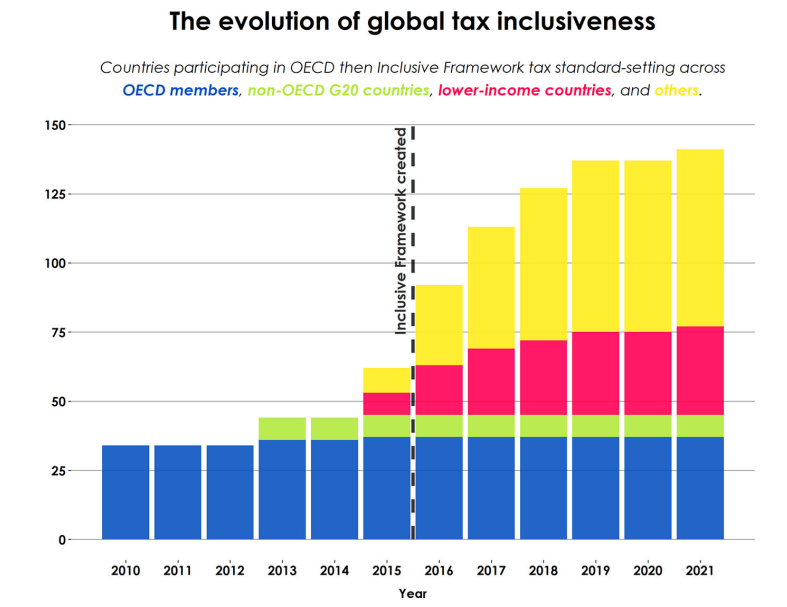

Figure 1: The evolution of tax inclusiveness (Hearson et al., 2022, p. 8)

Previously, low-income countries in Sub-Sahara Africa were largely excluded from OECD-centered norm-setting platforms (see Figure 1), and Richard Kweitsu notes that international taxation for long gathered limited attention within domestic revenue administrations. But nowadays, “tax multilateralism […] offers […] an overnight experiment in mass integration of developing countries into historically Northern-led global governance” (Hearson et al., 2022, pp. 8-9). In 2010, the OECD allowed developing countries to attend global tax meetings as an observer, but from 2015 onwards, countries could participate “under equal footing” through the Inclusive Framework and membership within the framework increased to 135 members[3]. Yet, the legitimacy of this framework is debated. Prof. Magalhães calls it frustrating that “the OECD hangs on to this idea of an ‘Inclusive Framework’ despite lacking common understanding on how it works in practice. Participants even question its inclusiveness as they often do not get voice, or get to decide. Initial outputs of this framework generally fail to take developing country interests into account, and these end up being criticized, and later on amended.” This process shows a lack of inclusivity, and there is a gap between formal and effective participation as meetings take place in Paris, are highly technical, and preparatory work is performed without the Inclusive Framework (Hearson et al., 2022). Richard Kweitsu therefore anticipates that African countries have a better chance of real representation within the UN.

The work of this ‘Framework’ perversely added to the momentum of the Africa Group. Prof. Magalhães clarifies that: “once the OECD started opening up, it lost a bit of power. Not completely – because the framework is not truly inclusive – but it did lose some power as the discourse became relevant to others and countries started to complain. Finally, we got to a point where there was enough political momentum to make this United Nations proposal. It is also remarkable to witness how the discourse on developing countries and international taxation changed in the last decade. Where no one talked about developing countries in global tax debates in the past, you now cannot not talk about developing countries when discussing international tax”.

Taking back taxing rights.

Next to expectations for a more legitimate tax regime, there is hope that a shift towards the UN would readdress current disadvantages of developing countries in international tax. Research highlighted how developing countries “negotiate their taxing rights away” through bilateral tax treaties (Hearson, 2018), struggle to administrate transfer pricing rules (Vet, 2023), and loose scarce resources through profit shifting behavior (Cobham & Jansky, 2019). According to Prof. Magalhães developing countries tried to change some these inequities before, and previously pushed for ideas such as exclusive source taxation within the UN Tax Committee. This proposal did not move forward because high income countries opposed this idea, and wanted to keep things at the OECD. However, Richard Kweitsu stresses how the rise of big tech companies in Sub Sahara Africa increased their awareness about the distribution of taxing rights, and Prof. Magalhães notes how this rise pushed the OECD towards reopening the discussion on taxing rights. In his view, the OECD, by doing so, created opportunities for other countries to launch complaints on the distribution of taxing rights, while they nevertheless tried to control the discourse.

Still, Prof. Magalhães emphasizes, “taxing rights, especially legally speaking, come from countries sovereignty, and are not given by treaties, or institutions, let alone the OECD that has no power to legislate, or even the UN. The debate on global rules is a debate about whether there are any limits to taxing rights, and so far we agree that limits are those that countries impose upon themselves and they do that through tax treaties. Therefore, if the system is flawed and does not allow you to tax enough, it is either because you signed a treaty that restricts you, or because other countries are pressuring you to tax in a certain way. The reason why the OECD opened the discussion on taxing rights in the digital economy is because European countries have a lot of treaties as were capital exporters and these treaties work in favor of capital exporters. But what happened over the years, when the global economy changed, is that a lot of European countries became source countries, mostly to the US, and therefore wanted to get out of their treaty obligations”.

Looking forward what is the potential

One UN tax expert, Mr Rasmi Das[4] claimed that adopting this UN resolution is the “most significant event ever towards making the international tax system fairer, more equitable, and sustainable in the long run.” Prof. Magalhães used to have a rather skeptical outlook on the UN’s potential to take on global tax leadership, and was influenced by literature portraying the UN as a weak institution, dominated by some players that achieved little for developing countries. Instead, his conclusion was that developing countries should have their own institutions regionally, and he rather incentivized pluralism in tax design, have coordination first at the regional level before taking things up to the next level. Richard Kweitsu underlines how African countries initiated more regional cooperation through the Africa Tax Administration Forum and the subcommittee on illicit financial flows within the African Union, and how this increased regulatory capacity, and global representation. Regardless, Prof. Magalhães realized that it is not evident for developing countries to roll out regional regimes, and African countries are reluctant to break away from global standards as they fear that this would hurt their investor attractiveness (Vet, 2023).

Thus, both Prof. Magalhães and Richard Kweitsu felt excitement when reading about this UN resolution mandating the UN to design a plan to take up global tax leadership. Prof. Magalhães mostly because of his frustration that the OECD “continues to insist on a single discourse, and proposed ideas that have little to do with developing countries”. His preferred solution lies regionally, but regardless he believes: “that pushing things towards the UN, could be a tipping point”. However, countries also restrict their taxing rights because of power, and we should therefore not be naive in expecting a level playing field for developing countries when renegotiating taxing rights at the UN. First of all, high income countries are part of the UN, and although there will be more voices in decision-making processes, these countries will also try to keep what they have. Secondly, this resolution authorizes the Secretary General to come up with a plan but remains vague on the practicalities of the further process. How will future plans for instance connect and integrate the work of the OECD? Prof. Magalhães gives us a few things to look out for when looking for real change. First, a restructuring of the tax committee of the UN, and an extension of their work is an important indicator. Because if the UN wants to compete with the OECD, their real challenge is that there are a lot of people working on tax at the OECD as it is a tax norm producing machine. Secondly, a positive indication would be if the UN would put governance, legitimacy and institutions explicitly on the agenda. Something that has hardly been done within the OECD process.

Cobham, A., & Jansky, P. (2019). Measuring misalignment: The location of US multinationals’ economic activity versus the location of their profits. Development Policy Review, 37(1), 91-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12315

Hearson, M. (2018). When Do Developing Countries Negotiate Away Their Corporate Tax Base? Journal of International Development, 30(2), 233-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3351

Hearson, M., Christensen, R. C., & Randriamanalina, T. (2022). Developing influence: the power of ‘the rest’ in global tax governance. Review of International Political Economy, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2039264

Vet, C. (2023). Diffusion of OECD Transfer Pricing Regulations in Eastern Africa: Agency and Compliance in Governing Profit-Shifting Behaviour. ICTD Working Paper (164). https://doi.org/DOI: 10.19088/ICTD.2023.022

[1] Ms. Amina J. Mohammed, deputy secretary-general to the UN, made this statement during the UN Tax Meeting on the 31st of March 2023. Special meeting on international cooperation in tax matters – Economic and Social Council, 16th plenary meeting | UN Web TV

[2] UN resolution for an intergovernmental tax framework: What does it mean, and what’s next? – Tax Justice Network

[4] Mr Rasmi Das made this statement during the UN Tax Meeting on the 31st of March 2023. Special meeting on international cooperation in tax matters – Economic and Social Council, 16th plenary meeting | UN Web TV