When it comes to competitive international grants for research, education and internationalization, African HEIs appear to be missing out. If we take the example of South Africa within the EU Erasmus+ Capacity Building in the Field of Higher Education programme, we see that until the 2018 call, only three of the 17 funded projects were coordinated by South African universities and those three are among the top universities in the country. Disadvantaged universities lag behind, even when they can count on academics who actively participate in projects despite a lack of leadership and huge administrative burdens. Experiences in the EU and South Africa have proved that investments in support services and training for project writing and management may play an important role in changing this situation. There is no magic formula, however, and each institution must decide which approach is most appropriate way for its situation.

Case study background

Within the IMPALA working group ‘Project writing and management’, the International Relations offices of four South African universities (Cape Peninsula University of Technology, University of Venda, University of Limpopo and University of the Fort Hare) carried out an analysis with the aim of designing a sustainable development plan for setting up support services for project writing and management. The analysis described below is the result of a questionnaire filled in by international relations managers, observations made during training sessions for local academics and staff, and a field visit in May 2018.

IMPALA partners: where they were

The four IMPALA partners were historically disadvantaged institutions in South Africa. While each of them has an International Relations Office (IRO), these units are rather small, employing between 2 and 5 staff, and their focus is on managing international students and increasing the number of partnerships in Africa and worldwide. These two goals are the core objectives of their mission and tend to absorb the bulk of their human resources. In addition, a high staff turnover, mainly at management level, has not contributed to stabilizing development strategies and policies.

In terms of project participation, the following characterizing elements emerge:

1. Strong focus on national funding. The questionnaire highlighted that the IROs are aware of and informed about national funding but are not familiar with international funding instruments; neither do they implement fundraising activities, including looking for opportunities available in the competitive grants landscape.

2. Used to being invited, not leaders. They do not put themselves forward as coordinators due to a lack of resources and skills.

3. The IROs do not always have a clear picture of which projects their institutions and academics are involved in. Lots of information is retained at the peripheries in academics’ hands.

4. Academics participate in international projects through individual choice, often by external invitation, and not because of a strategic institutional push for it.

5. Academics are faced with the absence, or reticence , of administrative support when it comes to the management phase. They may experience a lack of support when facing daily challenges connected to administrative documents and the information needed to join a project, which may not be easily accessible, as well as the management of exchange rates and accounting documents in line with donors’ expectations. Such challenges may put them at a disadvantage compared to their peers.

6. Poor project writing skills. This appeared during the initial phase of the IMPALA training sessions, during which it became evident that trainees paid little to requirements and rules, taking no care in the project design and writing style because of their conviction that a strong idea would be the main selection criterion.

7. Dichotomy between Research office and International Relations offices. Research offices are in charge of funding opportunities but, according to the information collected, their tasks are mainly focused on promoting national grants and they do not follow up on the writing and management phases. And what about funding that does not target research directly? It seems that there is no unit promoting or monitoring it.

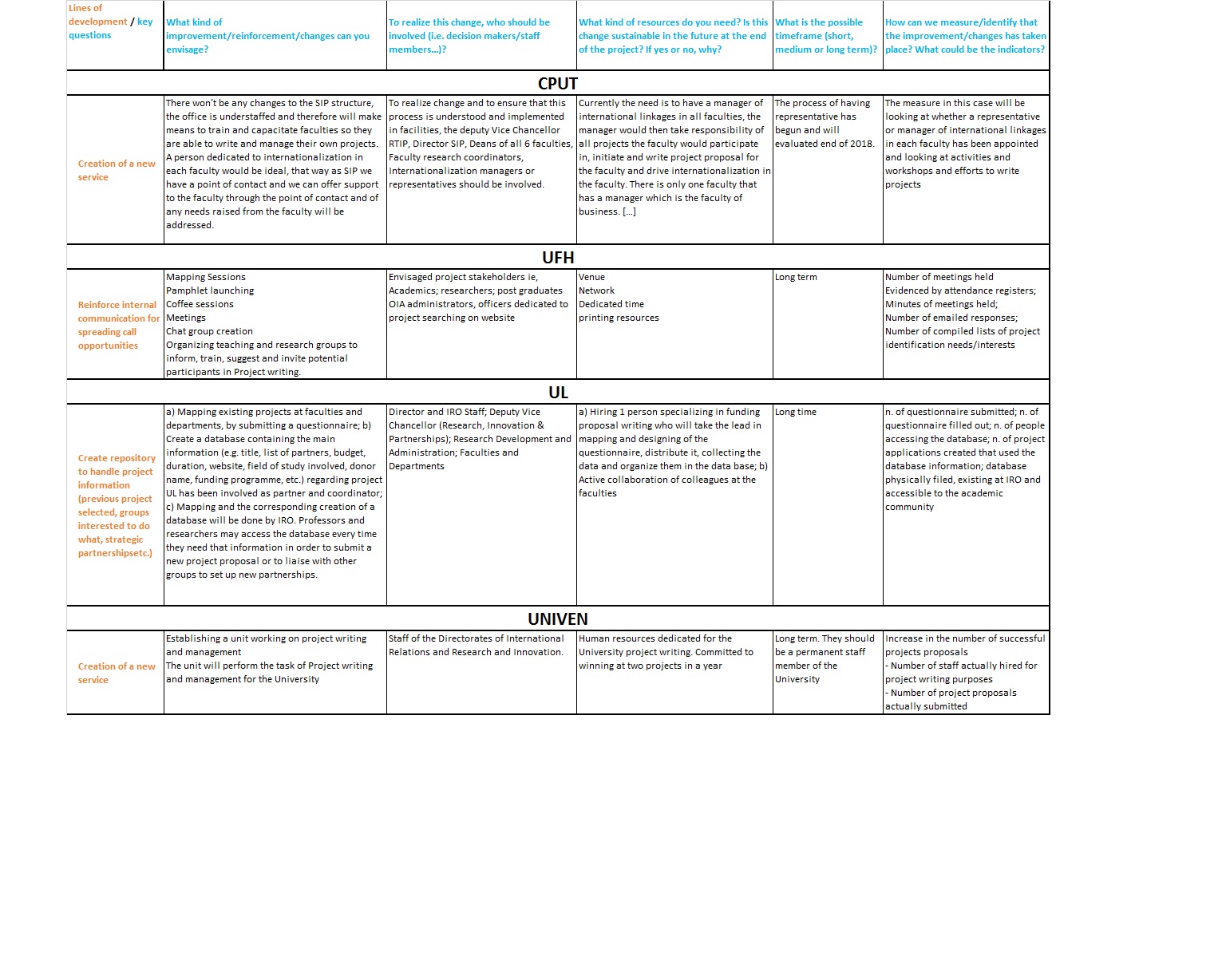

IMPALA partners: where they want to go

The four partners have been called to ask some key questions along the suggested lines of development, such as ‘Creation of a new service’ or ‘Reinforce internal communication for spreading call opportunities’. The result is an initial Plan of Action per partner, as shown in the following examples:

As emerged from the four Plans of Action, and given that the IROs’ human resources will not increase in the near future, it is unlikely that a new unit or mature service can be set up in the short term. However, the partners are considering a start-up phase involving incremental increases in services, which means adding small tasks to the weekly schedules of personnel already available.

In particular, two types of start-up phases emerged from the analysis done by the partners:

1. UFH, UL and UNIVEN are more likely to reinforce central services offered by the IRO starting from the strategic decision to first systematize existing experiences by mapping projects, as well as intercepting academics’ interests in specific geographic areas or topics in order to gain a clear understanding of the institutions’ own academic community and to create a repository of administrative material which can be used by the entire community. The second step will be to monitor international funding opportunities also beyond research, to cover those fields which are currently unexplored by existing fundraising units, and consequently to promote them within the academic population to stimulate participation.

2. CPUT decided instead to opt for a decentralized model by setting up specialized teams (involving administrators and academics) for project writing and management at faculty/department level, where more resources are likely to be mobilized, while the central IRO maintains a general overview of international partnerships. Owing to its dimension and resources, the Faculty of Business has been identified as a pilot case for testing this model.

In both cases, the institutions identified two sine qua non conditions:

• Each change requires the involvement of governance (Deputy Vice-Chancellors, etc.);

• There is a shared need for more internal networking: be more connected with other offices, namely Research offices, and raise awareness about what internationalization is all about, beyond the management of international students.

One ‘catalyst’ element was also identified:

• The four institutions plan to capitalize on the community of practice that emerged from the IMPALA training, which can help the partners team up with professors who are already active in projects and act as facilitators for colleagues who want to embark on international projects for the first time.